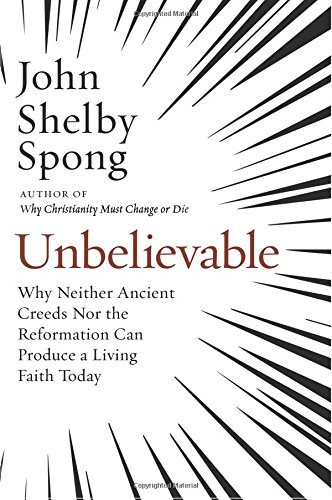

This book study begins September 30, 2018.

Five hundred years after Martin Luther and his Ninety-Five Theses ushered in the Reformation, bestselling author and controversial bishop and teacher John Shelby Spong delivers twelve forward-thinking theses to spark a new reformation to reinvigorate Christianity and ensure its future.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Christianity was in crisis—a state of conflict that gave birth to the Reformation in 1517. Enduring for more than 200 years, Luther’s movement was then followed by a "revolutionary time of human knowledge." Yet these advances in our thinking had little impact on Christians’ adherence to doctrine—which has led the faith to a critical point once again.

Bible scholar and Episcopal bishop John Shelby Spong contends that there is mounting pressure among Christians for a radically new kind of Christianity—a faith deeply connected to the human experience instead of outdated dogma. To keep Christianity vital, he urges modern Christians to update their faith in light of these advances in our knowledge, and to challenge the rigid and problematic Church teachings that emerged with the Reformation. There is a disconnect, he argues, between the language of traditional worship and the language of the twenty-first century. Bridging this divide requires us to rethink and reformulate our basic understanding of God.

With its revolutionary resistance to the authority of the Church in the sixteenth century, Spong sees in Luther’s movement a model for today’s discontented Christians. In fact, the questions they raise resonate with those contemplated by our ancestors. Does the idea of God still have meaning? Can we still follow historic creeds with integrity? Are not such claims as an infallible Pope or an inerrant Bible ridiculous in today’s world?

In Unbelievable, Spong outlines twelve "theses" to help today’s believers more deeply contemplate and reshape their faith. As an educator, clergyman, and writer who has devoted his life to his faith, Spong has enlightened Christians and challenged them to explore their beliefs in new and meaningful ways. In this, his final book, he continues that rigorous tradition, once again offering a revisionist approach that strengthens Christianity and secures its relevance for generations to come.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Week 8 Questions

1 – What replacement for “reward the good, punish the bad” is now used because it works better? 257

2 – When have you noticed the church working in behavior control mode? 258

X – Don’t read Spong for your cosmology. 265

3 – Compare god to emergent properties. 268

4 – What do you think/feel about universal consciousness? 270

5 – As a community of seekers, how would you limit that seeking?

6 – What’s wrong with “If the institution is to live into the future, it must recover its original meaning and identity.”? 274

7 – What aspect of Christianity do you think “has been found difficult and not tried”? 274

8 – What else might Matthew have meant by “You are to proclaim the gospel.”? What would you mean by it today? 275

9 – Spong describes his vision of ideal Christianity. What should we be doing to achieve that goal?

Responses to Questions for Week 8

1. What replacement for “reward the good, punish the bad” is now used because it works better? [p.257]

If, along with Spong here, you’re still talking about child-rearing, it might be “reward success, criticize failure” – but I’m not sure that would work very well either. Maybe it ought to be something like “reward effort, discourage laziness” or “reward accomplishment, educate failures.” If, however, you’re talking about the ways in which the Church has used “heaven” and “hell” (since that’s the focus of this chapter), then use them only as they relate to this life (which is the only one we know anyway) and forget about bringing up any such a dichotomy as a destiny in the afterlife.

2. When have you noticed the church working in behavior control mode? [p.258]

It’s been a form of “behavior control” whenever the Church has insisted upon an orthodox or doctrinal position to the point of dogmatism (i.e., what one must or must not believe). That then just becomes arbitrary, arrogant, even tyrannical. At least heretics aren’t being burned at the stake anymore, and yet, alternatively, they have been shunned and run out of the Church – even formally excommunicated.

X . Don’t read Spong for your cosmology. [p.265]

So, what do you think of Spong’s comment here that “the possibility of life must always have been present or it could not have emerged.”? Where did life first come from anyway? How did it originate? What, exactly, is the current scientific thinking about the origin and development of the universe? Is it that, just before a period of very high density, there was a singularity which became the Big Bang? How would you explain the origin of sentient life? I confess that I do not know – and the book of Genesis for me is just a symbolical narrative, a mythological allegory.

3. Compare god to emergent properties. [p.268]

It’s not clear to me what you mean by “emergent properties.” If, by that, you mean a collection or complex system whose property isn’t present within individual components within the system, then it sounds, to me, a lot like Aristotle’s point that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” To compare that to God might be something like panentheism: that God is greater than the universe and yet is included and interpenetrates it – even extending beyond time and space itself. I’m sort of there, I think, but the whole concept of God remains to be an ineffable Mystery for me – and not at all some kind divine sentient being who’s keeping an eye on us. That’s why prayer for me is so problematic; I don’t “talk to God” because that kind of god-in-our-image just isn’t there for me. But, then, who knows for sure? I don’t.

4. What do you think/feel about universal consciousness? [p.270]

The phrase that Spong uses here is “the collective unconscious” and I think originated with Carl Jung. It’s a bit like saying that our ancestral memory, joined with our inherited experience, gives rise to a kind of shared wisdom. In that sense, yes, I do believe that we are “linked with people who lived before us” and we will be with those who will live after us as part of their memory of us. I’ve always said that we “stand on the shoulders” of an endless line of saints. Now, if we’re doing our part, we will provide “the shoulders” upon which others will stand in the future. Obviously, there will always be some people who will care only for themselves without any regard to what went on before and feel absolutely no responsibility whatsoever for what comes after them. That comes close to what psychologists have called a narcissistic personality disorder – and we have far too many of those people around these days.

5. As a community of seekers, how would you limit that seeking?

I could play the devil’s advocate with that question and simply say that if you were to limit seeking, in any way, then you would no longer have a “community of seekers.” You would have what biologists and social psychologists refer to as a “herd mentality” – people who’ve become like animals and no longer think for themselves but simply go along with what everybody else is thinking and doing. If, by “seeker,” you mean an adventurer, experimenter, pathfinder, or just an all-around inquisitive person, then we need more of those, not less. Without seekers we will become a people simply content with the way things are and not be able to envision how we might make life better. We won’t find it if none will seek it.

6. What’s wrong with “If the institution is to live into the future, it must recover its original meaning and identity.”? [p.274]

The trouble with that statement is that not everyone will agree what the “original meaning and identity” actually was. Spong is hoping that means “a universal community” (undivided, neither condemning nor authoritarian, without creeds or tribalism, and “in favor of universal inclusiveness”), but given the nature of human beings, I doubt that we’ll ever come to a collective agreement on just how to live out such a community. Somebody will always want to tell others what to do, how to behave, and what to believe. I do agree, though, with G.K. Chesterton’s statement there that “Christianity has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and not tried.”

7. What aspect of Christianity do you think “has been found difficult and not tried”? [p.274]

So, okay, how about “love your enemies” or “love your neighbor as you love yourself” – or other such sayings from the so-called “Sermon on the Mount” – as a place to begin? Significantly enough, such sayings didn’t originate with Jesus, however (cf. Matthew 5: 43 with Leviticus 19: 18), so history does seem to show that such behavior “has been found difficult and not tried” – at least not for long or creatively enough to have made it last. Still, we ought to keep trying.

8. What else might Matthew have meant by “You are to proclaim the gospel.”? What would you mean by it today? [p.275]

I do like Spong’s suggestion here that it’s also “a call to build a world in which human oneness can flourish…a call to universalism.” I’d want to be clear, however, that what he meant by “universalism” is not what is often defined as “the doctrine that emphasizes the universal fatherhood of God and the final salvation of all souls” – that’s uncomfortably much like what’s called “apocatastasis” which is the doctrine describing “that Satan and all sinners will ultimately be restored to God” at the end of time. All too often that’s been the interpretation of “universalism.”

Proclaiming the gospel has got to be “good news” for everybody, not just for religious fundamentalists or those labeled as “faithful followers of Christ.” And it’s not that “human divisions must disappear” (as Spong says here), but that in spite of those divisions we’re still meant to feel good (i.e., experience “good news”) about ourselves as well as toward our neighbor – and that means, most often, in spite of our differences. Yes, it is meant to be a celebration of “human oneness” (p.276), but in the sense that we are all worthy of respect and acceptance in spite of our different cultural and religious points of view. We all have the right (as it’s been illuminated elsewhere) to pursue “life, liberty and happiness” in our own way – just as long as it doesn’t infringe upon those same rights for others, and, yes, “loving our neighbors as ourselves.” That would be good news. That would be proclaiming the heart of the gospel.

9. Spong describes his vision of ideal Christianity. What should we be doing to achieve that goal?

To pick up where Spong leaves off – that this is “an invitation for all to dwell in the joy of capital-B ‘Being,’” [p.276] – I think an ideal version of Christianity would be one that supports every human being’s innate capacity to become whatever he or she wants and is able to become. In my mind, this is very close to Abraham Maslow’s vision of the height of “being” in his model of the hierarchy of human needs (cf. the model at https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html). It’s the ideal of every human being realizing his/her potential of “self-actualization” – realizing one’s full potential or (oddly enough, as a slogan in the U.S. Army has put it): “being all that you can be.” As far as what we should be doing to achieve that goal, it should be constructing the kinds of cultures and political systems in which every single person is given just that opportunity. For those who need an extra assist (due to income disparity, disability, social status or any other impediment) an “ideal Christianity” would meet that need.

So, I would disagree with Spong, a bit, in his statement that “Christianity is not about religion….” [p.278]. It should express what any legitimate religion is meant to be. “Religion” (from the Latin religare) is meant to express the recognition of all that “binds us together” as human beings. It addresses both a personal as well as a communal devotion toward a higher aspiration that’s meant to be a conscientious concern for, as well as a complete commitment to, whatever matters most in life: our values. It ought to be a total way of interpreting and living life. That’s what religion was first meant to be and what it still might become – if, individually and collectively, we have the will for it.

Week 7 Questions

1 – Why do you think Spong chose to talk about prayer by telling stories? 238

2 – When I read the “if God has the power...” questions on pg. 241, they seem most applicable to an anthropomorphic god. Do you see these statements another way, and if so, how?

3 – Have you ever had a powerful experience that was later deflated by a weak prayer? 248

4 – What does: “Prayer ...is the practice of the presence of God...” mean? (to you?) 254

5 – How do you use the words heaven or hell? 259

6 – Has religion ever NOT been int the behavior control business? 261

7 – Do you see any connection between “heave and hell” and life after death? 262

8 – What is your view of universal consciousness? 267

9 – Is chapter 35 any more than wishful thinking? 270

Responses to Questions from Week 7

1. Why do you think Spong chose to talk about prayer by telling stories? [p.238]

It just makes the issue more real and less academic. It’s better to be personal about your prayer – as well as honest about what it is and what it is not. I have always had trouble with prayer – particularly intercessory prayer. But when I left the God that I was given and turned to the One I needed, prayer became the story of my life and how I interact with other people’s stories. Sharing in one another’s stories can teach us compassion and empathy – two very essential aspects of prayer, as far as I’m concerned. Spong makes a good point that, for him, prayer is a “life-giving experience” [p.240] – I mean, consider its opposite (e.g., shaming, guilt-creating, dependence upon outside authority, etc.).

2. When I read the “if God has the power...” questions on pg. 241, they seem most applicable to an anthropomorphic god. Do you see these statements another way, and if so, how?

That’s Spong’s point about the problem of prayer, after all, and why he said on the previous page, “I no longer understand it to be the petition of one in need to One who has the power to meet that need.” It then becomes “a delusional game of magic” [p.240]. Still, he does dissemble a bit when – in talking later about how he and his wife prayed for their daughter: “We held her in our hearts before God as we do all those we love when they are in ‘trouble, sorrow, need, sickness or any other adversity’…” I wonder what he really meant by that phrase, “We held her in our hearts before God”…? That sounds very much like turning toward that ancient and traditional image of an anthropomorphic god. So, I’m much more comfortable with his later explanation that, for him, “Prayer is the sharing of being, the sharing of life and the sharing of love” [p.248]. It is that…but much more. For me, poetry is prayer.

3. Have you ever had a powerful experience that was later deflated by a weak prayer? [p.248]

It happens to me all of the time – most often when I am in any traditional church or being led by someone with a very conservative or distinctly evangelical point of view. I was moved by the music, the power within the gathered community, a skilled and thought-provoking sermon, … and then somebody offers a pious and theistic prayer and I feel as if they’ve completely missed (or made a mess of) everything that had gone before. Oddly enough, that other person thinks that they’ve affirmed or even embellished upon what preceded them. Still, I find such moments very unsettling.

4. What does: “Prayer ...is the practice of the presence of God...” mean? (to you?) [p.254]

To me it means finding ways to place yourself in the Presence of all that you consider to be profoundly Holy. It means paying attention to that Presence and its movement in all of life. But, like any discipline, such a spiritual discipline takes practice, patience and repetition. That’s how I understand the powers of meditation and contemplation – as well as what happens in a worship “service.”

5. How do you use the words heaven or hell? [p.259]

I don’t, usually. But when I do it’s only to either debunk them or compare them to real experiences that we’ve all had in this life – the blissfully beautiful (i.e., heaven-like) or the just plain hellacious. In my theology, they’ve nothing at all to do with some mythical places that we all will experience after death. They’re here or they’re nowhere.

6. Has religion ever NOT been in the behavior control business? [p.261]

Yes – but only in those religious communities in which behavior is not strictly proscribed and where difference is either accepted or even welcomed. These communities are there; you just have to look for them. I do have to say that I’m using the word “religion” in its broadest sense as meaning that which binds us together or that celebrates our highest values. I’ve even seen it happen in churches!

7. Do you see any connection between “heaven and hell” and life after death? [p. 262]

Of course, that’s how the terms are most often used. Depending upon your behavior in this life you’re consigned to either one or the other. I don’t believe this, but that’s how they’re used. Human beings have always wondered what happens after death and whether or not it makes any difference at all how we behave in this life that might then affect that “next life.” Is our identity simply extinguished after we die or does it take up existence somewhere else? Out of questions and speculations such as these, cultures invented the concepts of rewards and punishments (heaven or hell) to consider what might happen next. No one – I mean no one – knows for sure one way or the other.

8. What is your view of universal consciousness? [p.267]

Every human being has some level of consciousness – that’s just part of being alive. Do we all share in a greater collective consciousness? I think not. I don’t think that there’s anything like a single intelligent consciousness that pervades the entire universe – often referred to as the Universal Mind. Aristotle had an interesting insight, however, that any whole is greater than the sum of its parts. I believe that’s true. So, each of us is a kind of component within a greater system. Does that wholistic system itself, though, have a separate identity and greater consciousness. I don’t think so, but I do not know.

9. Is chapter 35 any more than wishful thinking? [p.270]

Maybe. I must admit, though, that I’m not as certain as Spong seems to be here when he says that…

“…at the edges of life, on the boundaries of expanded self-consciousness, the

concepts of transcendent reality, infinite love and eternal life still make sense to me.”

Is that simply “wishful thinking?” Who’s to say? None of us can either prove or disprove a concept like “transcendent reality.” There might be something to it. I do not know. I do agree with his conclusion at the end of this same page, however:

“The only place I can hold this conviction and prepare for what comes next is in a

community of seekers. That is what I ultimately believe the church must be. …

…church with all its imperfections…provides me with the place to touch and enter

‘the eternal.’”

I find within groups like ours (i.e., the Lutz Book Group, undergirded by the supportive scholarship of the Westar Institute) the nascent possibilities of what a reformed Church might look like. Sadly, however, it’s begun to look like the only way that will finally happen is to irrevocably pronounce a “good death” of the current institutional Church that has been our inheritance.

Week 6 Qestions

1 – The Ascension story seems to be very well explained by our author. Do you have any questions about this short section? 196

2 – Do you have another pair of situations where the same behavior is acceptable in one case but not another? 200

3 – Do you have a basic ethical system that you are satisfied with? What is a short description? 202

4 – What is your most interesting experience with the 10 Commandments? 205

5 – Take a look at Exodus 20, Deuteronomy 5 and Exodus 34. Comments? 212

6 – Where would you place yourself on an objective – subjective ethics scale ( O = 1, S = 10 )? 218

7 – What are you left to eat if you completely obey “Thou shalt not kill.”? 224

8 – Why do you think the large majority of the chapter on Modern Ethics is about sexuality? 231

9 – What other issues would you like to have seen in the Modern Ethics chapter? 233

Responses to Week 6 Questions

1. The Ascension story seems to be very well explained by our author. Do you have any questions about this short section? [p.196]

I’d like for him to explain what he means by using the word “real” here – that it was a “real” story?..., a “real” event?..., that it provided his followers with a real reason to carry on?…what? If, as Spong says, that it “was never intended to be, literally true,” then what’s real about it?

2. Do you have another pair of situations where the same behavior is acceptable in one case but not another? [p.200]

I can’t think of one, but then I’m a little uncomfortable when Spong says “Subjectivity in ethical judgments is thus inescapable.” It can lead to what’s been referred to as “situation ethics” – i.e., that it just depends upon the circumstances as to whether or not a behavior is moral. I’m troubled that Spong goes on to say that “Good and evil are not fixed categories” and “they never have been” [p.201]. Are there not some situations that are always evil? I think of things like child abuse, torture, or the starvation of innocent children as is currently happening in Yemen; are any of those ever “acceptable?”

3. Do you have a basic ethical system that you are satisfied with? What is a short description? [[p.202]

I think that I do – at least I work at it. From the roots of my family and Christian heritage, I am led to treat others as I would like to be treated.

4. What is your most interesting experience with the 10 Commandments? [p.205]

I think that it’s interesting – as well as regrettable – that in certain parts of these “United” States there are public officials who want to raise these ten to iconic status by building monuments to them and insisting that they be placed in the public square. These officials claim that we are a Judeo-Christian nation and so while these commandments should be at the heart of our worship, oddly enough – and only secondarily – do they don’t become the center of our ethical and legal systems.

On Election Day this year (November 6, 2018), Alabama voted to allow displays of the Ten Commandments in schools, courthouses, and other public places. But the U.S. is not and never has been, a “Judeo-Christian nation.” That isn't stopping Dean Young, the biggest proponent of the measure, from celebrating Amendment 1 as an “opportunity to go down in history as the first state to acknowledge that we want God, that is the Christian God, in their Constitution.” So, if you’re not in with this, you’re out – which means (even more disturbing) that you’re not welcome to be a citizen of these states that haven’t been “united” in a long, long time. Sadly, they may never be.

5. Take a look at Exodus 20, Deuteronomy 5 and Exodus 34. Comments? [p.212]

Exodus 20:

1) “You shall have no other gods before me.”

2) “You shall not make for yourself an image” to worship.

3) “You shall not misuse the name of the Lord”…

4) “Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy.”

5) “Honor your father and your mother”…

6) “You shall not murder.”

7) “You shall not commit adultery.”

8) “You shall not steal.”

9) “You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor.”

10) “You shall not covet….”

Deut. 5:

1) “You shall have no other gods before me.”

2) “You shall not make for yourself a carved image” to worship.

3) “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain….”

4) “Observe the Sabbath day, to keep it holy….”

5) “Honor your father and your mother….”

6) “You shall not murder…”

7) “And you shall not commit adultery.”

8) “And you shall not steal.”

9) “And you shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.”

10) “And you shall not covet….”

Exodus 34:

[the Ritualistic 10]

1) “Observe what I command you…”

2) “Take care not to make a covenant” with others…”tear down their altars…”

3) “…you shall worship no other god, because the Lord…is a jealous God.”

4) “You shall not make cast idols.”

5) “You shall keep the festival of unleavened bread.”

6) “All that first opens the womb is mine. … No one shall appear before me empty- handed”

7) “For six days you shall work, but on the seventh day you shall rest….”

8) “You shall observe the festival of weeks….”

9) “Three times in the year all your males shall appear before the Lord God….”

10) “You shall not offer the blood of my sacrifice with leaven… The best of the first fruits of your ground you shall bring to the house of the Lord your God…. You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s milk.”

It should be noted that the traditional 6th commandment, “You shall not murder” was traditionally first translated as “You shall not kill” (in fact it remains so for Roman Catholics). Curiously enough the word in question there in the original Hebrew has a broader semantic range than just “murder.” So, some theologians say that it was reinterpreted just to make room for killing that seemed to them to be justified – i.e. to allow for killing the enemy in a “just war” or in support of the death penalty. This is one aspect of the problem with most translations of ancient languages where my professor of Koiné Greek, Dr. Mickey Efird, might say, pointedly, “Pay your money and take your choice.” So, it seems, we have.

The list from Exodus 34 is more just a stream of verbiage unlike the other two and any reader is hard-pressed to come up with the number 10 out of it – as you can see that I tried. The number very easily could be more. Exodus 34 is most often understood as an expanded or ritualistic version of Exodus 20.

6. Where would you place yourself on an objective – subjective ethics scale ( O = 1, S = 10)? [p.218]

As to his source, I agree with Spong here when he says – quite emphatically – that “no code has God as its source” but then he goes on to say “and no code can or will endure forever.” I think that some aspects of a code agreed upon by most human beings could endure – if not “forever” than for a very long time, or virtually forever. “You shall not murder” might be one; “bearing false witness” might be another. I find it difficult, though, to place myself precisely on this sliding scale between objective and subjective – which probably means that I come out more on the subjective side. If I did have to narrow it down I’d probably be around an 8. I say this because here later in life I find myself saying quite often, like Fagin in the musical Oliver, “I think I’d better think that through again.”

7. What are you left to eat if you completely obey “Thou shalt not kill.”? [p.224]

To begin with, it’s been understood that this commandment was to be considered only in relationship to human beings, so it was never meant to insist that we become vegetarians. As I noted above, however, those who excuse legally sanctioned killing (e.g. in war or in support of capital punishment) say that it might be more “accurately” translated (so then rationalized?) as “You shall not murder.”

8. Why do you think the large majority of the chapter on Modern Ethics is about sexuality? [p. 231]

As individuals (as well as a culture) we still seem to be hung up on what to do or not to do with our sexuality. For some, the issue confronts them every single day with confusing choices.

9. What other issues would you like to have seen in the Modern Ethics chapter? [p.233]

I could come up with a pretty long list: equal education, equal access to healthcare (abortion, suicide prevention, mental health, et al.), war, famine, poverty, genocide, slavery, corruption (corporate and governmental), freedom of speech, affirmative action (in business as well as in education), rehabilitation of criminals, immigration (expulsion of refugees or providing sanctuary), respecting diversity and honoring difference, parenthood and raising a family, saving our planet (global warming, geoengineering, environmentalism, population control, soil degradation, sanitation, GMOs, et al.), welfare and charity, gerontology, palliative care (i.e. minimizing suffering, the right to die with dignity), medical experimentation, pharmaceuticals (cost, access, relative effectiveness, addictive substances, etc.), editing the human genome, the rights of other species besides homo sapiens, privacy, AI (artificial intelligence) and the place for robotics, the creation of synthetic life, safety standards, gambling, prostitution…. Okay, I’ll stop; the list seems endless!

Week 5 Questions

1 – What do you recall thinking / feeling about your first encounter with Atonement Theology? 153

2 – Comment on the quote from Augustine’s “Confessions” on pg. 158.

3 – Pg. 159 describes the Orthodox position of humanity, from “We human beings are all fallen… to the end of the paragraph. How would you continue the paragraph after “We human beings… ?

4 – Expand on Spong’s short description of a replacement for Atonement Theology. What, for you, is the most important piece? 166

5 – Suppose we call the highest (or most general) belief in the resurrection as: “You get another chance.” How much more specific are you willing to believe in the Gospel stories? 171

6 – Describe what you imagine Paul meant when he said “Jesus was raised by God to sit at His right hand”. 174 – 7

7 – If you are interested in resurrection, how would you describe what you would like to happen (since we seem to be having so much trouble with the Biblical descriptions)? 181

8 – Comment on the last paragraph? What do you think about Easter? 188

Responses to Week 5 Questions

1. What do you recall thinking/feeling about your first encounter with Atonement Theology? [p. 153]

Originally, I just thought that Jesus was executed by Rome for being a troublemaker. Only later did I begin to pay attention to just what the Church was claiming about that death. To me, it made a horror out of God as it could be seen as an example of the worst case of child abuse imaginable. What kind of “father” would purposely do any such thing to “his son?” But then this idea of the “benefits” of human sacrifice were around long before (as well as long after) the life story of one Jesus of Nazareth.

2. Comment on the quote from Augustine’s “Confessions” on p.158.

The quote in question of Augustine’s there is this:

“Thou, O God, hast made us for thyself alone and our hearts are restless until they

find their rest in thee.”

The problem with this view, to begin with, is the assumption that such a paternal/creator-like image for God is an actual one. We’ve absolutely no proof that it is. Secondly, it also assumes that all of us share in this “restless” yearning for some kind of reunion with our creator. Granted, it may be a very human feeling to wonder about and imagine such an event, but that doesn’t make it real. I may share in a kind of “restless” curiosity, myself, about our origin as a species, but that doesn’t mean that how the Church came to envision such a God is the correct one. In truth, no one really knows how we came to be as a species – except in the evolutionary sense. While it’s fascinating to wonder if such a reunion might ever take place, because the idea actually rests in a very human longing to be reunited with our parents, the probability of self-delusion is a strong one.

That the Church came up with a “solution” where original sin was the problem and salvation (through Jesus alone) was the only way to solve it, actually has only compounded the problem in my estimation. So, I agree with Spong here when he says that “the church turned God into a righteous judge who required satisfaction” and Jesus had “to suffer in order to satisfy some presumed divine need” [p.158]. This is deviously clever in that in ends up making the Church the only place where truth exists and, thus, the only voice one should listen to.

3. Page 159 describes the Orthodox position of humanity, from “We human beings are all fallen…” to the end of the paragraph. How would you continue the paragraph after “We human beings…”?

Tragically it’s just been the way in which the Church has codified “original sin” into human beings so that they could then vest in themselves the sole authority to be the place where people could go to be finally released from its grip – but only as long as they believed in the ways that the Church was teaching them to believe. So, “we human beings” must find our own way to save ourselves from self-destruction. The teachings and examples of such “holy” ones as Jesus can help, but it’s up to us to accept their wisdom and follow in their footsteps. If we do not, the annihilation of our species that might follow will be our own fault.

4. Expand on Spong’s short description of a replacement for Atonement Theology. What, for you, is the most important piece? [p.166]

To me the most important piece is recognizing that our “salvation” as a species will not come from outside or from beyond us. So, I do like Spong’s image here that we are “being called into a new wholeness from our sense of incompleteness.” This is actually at the heart of my own theology. The Hebrew term, shalom, does mean “wholeness” – but it also means “well-being,” “health,” “harmony” as well as “peace” at the last. I would add that the concept of “self-actualization” (becoming all that we were meant to be) as articulated by the philosopher Abraham Maslow, is a very close corollary. It may take another millennia or so of evolution, but – in the end – it will always be up to us to make it so.

5. Suppose we call the highest (or most general) belief in the resurrection as: “You get another chance.” How much more specific are you willing to believe in the Gospel stories? [p.171]

I don’t think that’s a good idea; it risks perpetuating the original meaning given to that event by the early Church. There never was a literal resurrection. It was never meant to mean the resuscitation of a corpse. Jesus died. He remained dead – in all of the physical aspects and meanings of the word “dead.” However, if you were to reinterpret that event as the ways in which the character and teachings of Jesus have continued to “live” on in those who’ve attempted to follow in his footsteps, then you’d have something worth believing in.

6. Describe what you imagine Paul meant when he said “Jesus was raised by God to sit at His right hand”. [pp.174 – 177]

I imagine that Paul means that everything that you need to know about how to live a “godly life” has been revealed to us in the life and teachings of one Jesus of Nazareth – so much so, that if there is anything like a “Heaven,” he’s there.

7. If you are interested in resurrection, how would you describe what you would like to happen (since we seem to be having so much trouble with the Biblical descriptions)? [p.181]

If by this you mean “life after death,” I’d like to think that something of who I am (the essence of my soul or identity) will continue to exist long after my physical being ceases. But, just because I’d “like” for it to be so, doesn’t mean that it’s ever going to happen.

8. Comment on the last paragraph? What do you think about Easter? [p.188]

I think that Easter ought to be reinterpreted along the lines of what’s said in Deuteronomy 30: 19, “…that I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses; therefore, choose life, so that you and your descendants might live.” Whenever we make a choice may it lead us toward giving or preserving life, not death.

Week 4 Questions

1 – If miracles started with Moses, what category do creation stories fit into that is different from miracles? 124

2 – Answer (or at least comment on) any of the questions about miracles on pg. 126.

3 – When did you first begin to question the crossing of the Red Sea? 131

4 – How do you look at expanding food supply miracles? 132

5 – What purpose do you see in the movement of miracles from Moses to Joshua and from Elijah to Elisha? 138

6 – Are you convinced by Spong’s argument that “The Lazarus story is thus anything but literally true.”? 146

7 – What do you think of Spong’s interpretation of the Jewish year of festivals with the Synoptic Gospels? 149+

8 – What is the difference between “biblical happenings” and “interpretive symbols”? 152

My Responses to the Questions of Week 4

1. If miracles started with Moses, what category do creation stories fit into that is different from miracles? [p.124]

There never were “miracles,” of course; this was simply the culture’s way of proclaiming that their guy was special – an instrument of God. What’s different from the creation stories, in my opinion, is that those were myths, not miracles really, that were meant to explain how we came to be – again, every culture has its own version of these events. Judaism even borrowed some of these stories from the surrounding cultures (e.g., stories of the great flooding of the known world that became “Noah’s story”). None of these are meant to be taken literally (i.e., as historical events).

2. Answer (or at least comment on) any of the questions about miracles on p.126.

Once again, we’re talking about myth here, not fact. They were part of one culture’s legendary explanation of its opposition to another – the earlier one, at least initially, more dominant. There never was any “supernatural power of God” in this story of conquest, slavery, and then escape: Exodus. As Spong puts it here (and rightly so, I think):

So in our attempt to understand miracles in religion, we note the fact that they entered

the biblical story in the service of tribal needs, to validate the quest for Hebrew freedom

and to inflict pain and suffering, or to deliver people from the perils of life.

In answer to his final question, “Were miracles real?” my answer is simply no, not at all.

3. When did you first begin to question the crossing of the Red Sea? [p.131]

I suppose it was when I first saw the movie, “Moses,” starring Charlton Heston when I was eleven years old (1956). The “parting” of the sea made for some dramatic theater – and Heston played it to the hilt – but I remember asking myself, “C’mon! Would God do that?” Years later I learned about the great tidal surges at the so-called Sea of Reeds, a marshy area that’s part of the Isthmus of Suez. That seems to fit as the source of what later came to be viewed as a miraculous escape event.

4. How do you look at expanding food supply miracles? [p.132]

Again, these stories were part of mythic events created to elevate the so-called “miracle worker” in the eyes of the people within that culture so that they would view him (or, in the case of Thecla, “her”) as especially empowered by God and, therefore, God’s unique messenger. Jesus wasn’t the first, nor was he the last, to be imbued with such status. So, attempts by interpreters to literalize or explain these stories (e.g. in the “feeding of the multitude”) by saying, for example, that everybody had brought food pocketed in their clothes or already in baskets and that the “real miracle” was being moved by Jesus to share all that they had, is just missing the point.

5. What purpose do you see in the movement of miracles from Moses to Joshua and from Elijah to Elisha? [p.138]

As I’ve noted in my responses above, these legends were simply the narrators’ way to claim that these four (along with others made so noteworthy elsewhere in the Bible) were especially touched by God – so we’d better pay attention to them, listen to them, and “vest” them with particular authority. [NOTE: In my opinion, there is a clear etymological connection here with the garments of the clergy referred to as “vestments” – although, I hasten to add, I know of no clergy person who ever legitimately claimed to be a miracle worker!] I agree, then, with Spong’s conclusion on p.140:

“…they were never intended to be supernatural stories of divine power operating through

a human life. Perhaps we have been defending an idea that even the biblical authors

never intended.”

Yes, exactly so. Once again, as that highly respected biblical scholar, John Dominic Crossan noted:

“My point, once again, is not that those ancient people told literal stories and we are now

smart enough to take them symbolically, but that they told them symbolically and we are

now dumb enough to take them literally.”

6. Are you convinced by Spong’s argument that “The Lazarus story is thus anything but literally true.”? [p.146]

I didn’t need Spong’s help to conclude that it wasn’t literally true. It’s just one more part of the many stories that arose around the people’s experience of this charismatic and itinerant rabbi from Nazareth named Jesus.

7. What do you think of Spong’s interpretation of the Jewish year of festivals with the Synoptic Gospels? [pp.149+]

I respect his conclusions that these stories were meant to both affirm and confirm Jesus of Nazareth as that culture’s long-waited-for Messiah. As he says, “These miracle stories were interpretive symbols, not biblical happenings” [p.152]. In keeping with the cultures legendary heroes, the Messiah would be expected to do at least as much as those who’d gone before – and more. But just because an obscure prophet linked with Isaiah predicted it and the writers of the Synoptic Gospels included it. “We do not have to believe it” [loc. cit.].

8. What is the difference between “biblical happenings” and “interpretive symbols”? [p.152]

The former may or may not be actual (i.e., historical) events, the latter are the ways in which theologians – then and now – have come to interpret them.

Week 3 Questions

1 – How is Jesus different from you? What if we add his “last name”, Christ, and ask the same question? 81

2 – Where do you think the story of the original perfection of humanity came from? 83

X – The giant meteor was WAY SMALLER than Mars.

3 – What do you see as the next important step in human evolution? 89

4 – Conversation between Even and the serpent is the beginning of moral development. Comments? 95

5 – Why doesn’t Baptism work to wash away original sin? 98

6 – List some differences you see between the original (human) Jesus and the later Orthodox Jesus. 104

7 – What (if anything) do you lose when you realize that the Christmas stories in the Bible are myth? 109

8 – What portion of human babies are born to unwed mothers? Has this number varied significantly over time? 112

9 – How do you understand Jesus’ virgin birth? 117

Responses to Week 3 Questions

Week 3

1. How is Jesus different from you? What if we add his “last name”, Christ, and ask the same question? [p.81]

Aside from the fundamental fact that he was a man of his own time and culture – i.e., a Jew of the Ancient Near East who would’ve had no idea what this Post-Modern world would become – and even though I may know more about his culture than he ever could of mine, I think that he was a far more compassionate, intelligent and wise person than I am. His remarkable life and parables show it. So, even if you do consider him to have been “the Christ,” the long-waited-for Jewish Messiah, my response would be the same. In addition, however, I would have to make it clear to any fundamentalist (or even traditional) Christian, that Jesus and I share the same humanity. His elevation to divine status just tells us how important he was to that nascent Church, nothing more.

2. Where do you think the story of the original perfection of humanity came from? [p.83]

X – The giant meteor was WAY SMALLER than Mars. [What...?]

As a species, we’ve always thought of ourselves as getting better-and-better in practically every way: smarter, stronger, more innovative, masters of our domain. While, up to a point, it’s true, unfortunately we’ve carried on some of the negative aspects of our ancestry as well. We can be as savage and self-centered as any dominant animal still living “beneath” our species today. So, while even John Wesley (the early leader responsible for giving rise to The United Methodist Church) preached that the doctrine of sanctification meant that we were, in his words, “going on to perfection,” so far, it’s only been an aspirational dream, at best, and a tragic delusion at worst.

3. What do you see as the next important step in human evolution? [p.89]

The next necessary step is for us to learn the value of interdependence – or, in theological language, that we really do need to learn how to be “our brother’s keeper.” By helping others we help ourselves. We must cease our unreasonable and yet almost innate fear of the “other” and turn away from the kind of tribalism that’s given rise to every tragic conflict throughout our history on earth. If we do not, finally, learn to get along with each other and cooperate for the betterment of our world, we will end up destroying both that world and ourselves. As that insightful cartoonist, Walt Kelly, once had his cartoon character, Pogo, utter back in the 1950s: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” If we can evolve enough to release such enmity, we might then survive to make that next evolutionary step.

4. Conversation between Eve and the serpent is the beginning of moral development. Comments? [p.95]

Set aside the fact that this story is an allegorical myth, it’s not a very good moral teaching – a conniving creature created on whom to then blame our own self-centered immorality doesn’t show much “moral development.” It just led, inevitably, to the tragedy of Cain killing his brother Abel – which is yet another template of the historic enmity between farmers (Cain) and open-range herdsmen (Abel). Where have our ethics, then, come from? While much of the Bible does present us with principles, precepts, commands, warnings, guidelines, and counsels that are intended to move us toward that which is right and good, time and time again, it also witnesses to how often we’ve gotten it wrong and have lost our way. While there was nothing ethical about creation itself (even though God called it “good” and “gave” it to us), humanity did finally find ways of introducing ethical behavior into the mix. Did Eve and the serpent provide us with a good model from which to begin? I don’t think so. You could make a much better case for Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount – which was just his way of reasserting the essence of what Torah Judaism had always intended to begin with. So, “which came first, the chicken or the egg?”

5. Why doesn’t Baptism work to wash away original sin? [p.98]

Sadly, that’s been a corruption of the original meaning of that immersion ritual – which was meant to mark an initiate’s qualification for full religious participation in the life of the beloved community. While some might have thought so, there is absolutely nothing magical about it. Which is probably a good thing to know anyway, because if the invention of original sin by the Church was a sham, then there’s nothing to “wash” away! Both, however, do point to something about human nature that needs dealing with, and God will not be there to pick us up no matter how many times we fall flat on our faces. We need to dust ourselves off, get up, and start over again until we get it right – or, like Jesus, die trying.

6. List some differences you see between the original (human) Jesus and the later Orthodox Jesus. [p.104]

The original was a fully human being; orthodoxy turned him into a God/man. The original had a mother who got pregnant in the usual way and Jesus had blood-relative siblings; orthodoxy turned her into a beloved virgin who was impregnated by none other than God Himself (That still doesn’t let the actual father off the hook, though – whether he was Joseph or some other guy.). Regrettably, none of Jesus’ sisters or brothers got any of his magic. The original learned a lot from growing up within his family and his community; orthodoxy turned him into the Lord of the universe who knew it all from the very beginning. The original was a uniquely compassionate human being and teacher of profound wisdom; orthodoxy turned him into the Divine Savior and “third person” of the Trinity. The original Jesus was executed on a cross and his body was lost forever; orthodoxy turned that whole scene into a bizarre story of the resuscitation of his corpse that was then spirited “up into heaven.” The “real” Jesus could walk into your church today…and no one would recognize him.

7. What (if anything) do you lose when you realize that the Christmas stories in the Bible are myth? [p.109]

Like Santa Claus, you won’t really miss him when he’s gone. More importantly, you’ll then be challenged to see just what that myth represents and how important that realization might mean for you to then strive to live every bit as ethical a life as Jesus did – even one better than Santa Claus.

8. What portion of human babies are born to unwed mothers? Has this number varied significantly over time? [p.112]

Far, far too many. And while this number may have “varied significantly over time,” it is, nonetheless, every bit as much of a tragedy today as it was yesterday.

9. How do you understand Jesus’ virgin birth? [p.117]

It was an attempt by the early leaders of the Jesus Movement to make him into a star – or, even better, a Heaven-sent Savior who had more power and “tricks up his sleeve” than any of the emperors or religious leaders of his day. If Caesar could call himself “the son of a god,” the early Church had to go one better – an ultimate gotcha’ if you will – and make Jesus the true one-and-only Son of the true one-and-only God. He was so magnificent he didn’t even need a daddy. What’s even more curious, he shot right through his mother as if he actually didn’t need even her. Take that, you nonbelievers! Believe it, or to Hell with you! Well, that’s the story that I was told anyway.

[NOTE: These are just my first rambling thoughts in response to these questions as I head out on our vacation tomorrow morning. Maybe I’ll “clean it up” a bit when I get back!]

Week 2 Questions

1 – How do you go about “pleasing God”? How important is that to you? 51

2 – How are you constructing a successful replacement for the theisticly dead God? 53

3 – Is the God described on pg 58 too anthropomorphic? What happens to God when humans are replaced by the next step in evolution?

4 – Must theology be coercive? Can’t it just be descriptive? 62

5 – What (information?) is added to love when we say “God is the name by which we call the experience of love.”? Why not just use love and stop there? 65

6 – Spong cites only the positive connections of love among people as the God experience. What about negative connections? 66

7 - “[S]ecurity … turns out to be … idolatry.” Comments? 69

8 – Compare the Christianity Trinity to the particle / wave characteristics of light. 73

Responses to Week 2 Questions

Week 2

1. How do you go about “pleasing God”? How important is that to you? [p.51]

Phrases like “…to cause God to look favorably on us and our needs” or “…obedience to God’s rules…” or “pleas for God to have mercy” – all of these on this page mean nothing at all to me as I do not have an anthropomorphic understanding of God – i.e., as a supernatural being somewhere “out there” keeping an eye on us. That is completely unimportant to me. So, I do not “go about ‘pleasing God.’” I aspire to please my own sense of integrity. If there is any “controlling motivation” to my being and actions it’s as it’s been given to me, first, by my parents, then, by my teachers, later, by my extended family, friends, and the culture we share, but, finally, from my own sense of what is right or wrong, good or bad, life-giving or not. I certainly have no “punishing parent” nor “ultimate judge” images for God. As I’ve said, God remains to be an ineffable Mystery to me – a philosophical or theological construct if you will – but not any entity with “beingness” as we humans have come to think of our being.

2. How are you constructing a successful replacement for the theistically dead God? [p.53]

That’s a tough one. On the one hand, I mourn the loss of a loving and paternal God-image (maybe only because I was nurtured the most – from child to adult – by my own father and paternal-grandfather). And my earliest religious stirrings as a child were wrapped up in the “son-of-God” images of a deeply loving and compassionate Jesus. But as those lines from Paul’s letter to the Christians at Corinth say:

“When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child;

but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see in a mirror,

dimly, but then face to f ace. Now I know in part, but then I shall know just as I also

am known.” [1 Corinthians 13: 11-12]

I can no longer be a naïve child dependent upon others to shape my thoughts and beliefs. At this moment on my spiritual journey, then, I’ve replaced this “theistically dead God” with an awe-inspiring yet amorphous feeling of “the Sacred” or “the Holy.” It seems to have arisen out of my profound longing for a deeper sense of meaning and understanding of the universe and my particular place in it. But that is a feeling that I share with most, if not all, other human beings. From those first stirrings of wonder and awe at life and their surroundings, human beings always have invested in some kind of deistic concept of all that was beyond our comprehension. The trouble began when we began to make up answers to our incomprehension by inventing this theistic god in order to explain it all. I do not. But I remain in awe as I contemplate the universe and my place in it.

3. Is the God described on p. 58 too anthropomorphic? What happens to God when humans are replaced by the next step in evolution?

Well, this is Spong’s take on Isaiah, after all, and such phrases as “the kingdom of God” or “the ultimate reign of God,” still have inevitable connections to worldly kingdoms and the emperors who hold sway over them. So, in that sense, such language remains to be overly anthropomorphic. I’d give Spong credit, though, for attempting to move us away from that imagery as he interprets Isaiah this way:

“The presence of God, Isaiah was seeking to communicate, will be seen not in a being, but in the image of human beings achieving wholeness.”

He was speaking “of a reality beyond words.” Which is always the problem when we presume to speak about this truly infinite concept. Where I did pause, scratching my head though, was when Spong makes this claim:

“The divine can be seen only in and through the human. One must look inward not outward to experience the meaning and reality of God.”

What does that first sentence mean? To say “only in and through the human” seems like saying God can’t exist without us. While I take the next sentence to mean that we should finally and irrevocably get rid of this idea of a three-tiered universe – with a God-being hovering somewhere “up in the heavens” looking down upon “His” creation – if we are going to look, we ought to look everywhere, and not just inward or outward. If we do only look inward, the danger remains that we, yet again, will conjure up a god from out of our own wildest imaginings. That’s what I love about parables, though. In Spong’s words here, they’re “filled with symbols and pointers.” None of them “can be literalized.” So, even our language about “God” doesn’t reveal who or what “God” is. Our words about “God” remain to be symbolic and fallible attempts at describing an ineffable Mystery.

I'm uncertain how to answer your second question here, Peter. If human beings will be "replaced by the next step in evolution," I haven't a clue how that species will look or act. Some say it will be the dreaded AI (Artificial Intelligence) and so it won't be an evolution as much as it will be a takeover. If that does happen, I'm glad that I won't be around to witness it.

4. Must theology be coercive? Can’t it just be descriptive? [p.62]

Theology must never be coercive; it should only be descriptive. As Spong points out here (and, rightly so, I think): “Theology…represents little more than human attempts to organize the explanations.” What I find more intriguing about this portion, however, is when he says “Religion is not and never has been based on a divine revelation.” Oh, really? If he means by “divine” the magical conjurings of a theistic deity, I’m with him. But I see, hear and experience things that I would label as “divine revelations” all the time – in nature, in music, …in the eyes of my grandchildren. These experiences are not divine in the sense that they reveal a “Supreme Being,” but they are deeply religious, sacred, holy, …unusually lovely.

5. What (information?) is added to love when we say “God is the name by which we call the experience of love.”? Why not just use love and stop there? [p.65]

I think that throughout this section Spong is just speaking of how we experience God – i.e., as life, love and being all we were created to be. I can see where you might be troubled by his equating God with love (or with life or with being itself). I think that all he’s saying is that in knowing love, in knowing life, in knowing our very being, we may come to know that larger Reality that he wants to name “God.” As he says earlier, God is his “name for the transcendent dimensions of my own life. God is the name for the power and the source of life” [p.64]. As he speaks about love in that sense, then, he will come to the conclusion that “The more we give love away, the more we make the experience of God visible” [p.65]. On the following page, in this same vein, he can say that we all “are part of something greater than any of us can be. God is our name for this reality” and “the timeless eternity to which we are attached” [p.66]. Why not just live, love and be “and stop there?” Good question. You could do all of those without believing in God. But because Spong is wanting to stay connected to the Source, the Prime Mover in all of this, he wants to say that it all originates there. I may be with him in this.

6. Spong cites only the positive connections of love among people as the God experience. What about negative connections? [p. 66]

I’m tempted to say that those “negative connections” are the Devil in us! But, of course, I’d never mean that in the satanic sense. I will say, however, that as much as we can be possessed by goodness, we also can be possessed by evil. We can allow one or the other to consume us. The choice is always up to us, however, and is never due to the contrivances of the mythical creations of God or Satan that we find in the Bible. We are not victims in this. We can be both creators as well as destroyers. This fact is why I love the words of Deuteronomy 30: 19 so much: “I have set before you this day life and death, blessings and curses; therefore choose life, that both you and your descendants may live.”

7. “[S]ecurity … turns out to be … idolatry.” Comments? [p.69]

I think Spong’s point is further revealed within the next sentence, that “…certainty in religion is always an illusion, never a real possibility.” When it comes to the kinds of absolutes that have been codified in doctrines and dogma, I might agree with him. But if religion is defined (as I want it to be) as that which binds us together because it’s about what we most value – then such certainty isn’t just blind adoration, but comes out of a profound longing for community and the good that we can find in it.

8. Compare the Christian Trinity to the particle/wave characteristics of light. [p.73]

I’m not sure where you’re going here, Peter. As Spong says at the beginning of this page, “definitions of God” are “always definitions of human experience” – about our own understandings of God – so, “it is not about God.” The Doctrine of the Trinity is one of those [Never mind that sticking Jesus in the middle of that triumvirate and making them co-equal never worked for me!]. And as I understand that wave-particle duality in physics, light and matter exhibit properties of both waves and particles. [We’re talking quantum mechanics now here, so it’s way over my head!] Conventional concepts like “particles” and “waves,” though, just don’t completely explain the behavior of quantum objects. I think it was Einstein who first thought of light as a massless particle, called a photon, and that the flow of photons is then thought of as a wave. But if low energy photons tend to behave more like waves and higher energy photons behave more like particles, I am completely out of my depth in understanding this. If there is any comparison at all to the Trinity, finally, I don’t know what it might be. That doctrine has been nonsensical enough over the last couple of millennia; let’s just let it go, shall we?

Week 1 Questions

1 – What question(s) do you think the church should be trying to answer? 3

2 – What do you say to someone who believes there was an actual “virgin birth”? 9

3 – What do you think Christianity has to offer that a secular future does not? 14

4 – Have you ever done something that had consequences far beyond those you envisioned? 19

5 - “No one can escape from their own frame of reference.” Comments? 24

6 – How would you describe “the Christ experience”? 25

7 – Which thesis do you think is most significant? 26-29

8 – Describe your alternative to theism? 38

9 – How do you resolve the differences presented by the Bible and evolution? 48

Response to Week 1 Questions

Week 1

Part I – Setting the Stage

1. What question(s) do you think the church should be trying to answer? [p.3]

This is fascinating to ponder. To begin with, I can think of at least six: 1.) What do we value most in life? 2.) To what should we be devoted – personally and/or communally? 3.) How should we build such a community? 4.) How can we best commit ourselves to those values? 5.) How should we interpret and live the life we’ve been given? 6.) What, finally, “binds” us together (which is at the root of the meaning of the word “religion” – from the Latin religare, meaning “to bind”)?

2. What do you say to someone who believes there was an actual “virgin birth”? [p.9]

Unless you actually believe in a magical god, such a birth is physiologically impossible. By the way, this story from the Bible is a myth that was first invented by the author of the Gospel According to Matthew. That gospel was written some ninety years after Jesus’ actual birth from the body of a woman who had become pregnant in the usual way. This magical idea of being impregnated by God just was meant to elevate Jesus of Nazareth to be at least equal to or above those in power at the time who claimed that they had the right to rule over others because they, themselves, were gods (or the offspring of gods). Tradition tells us that a carpenter by the name of Joseph was the father, however, the truth is, we can’t be certain who Jesus’ father was. We have absolutely no way of knowing.

3. What do you think Christianity has to offer that a secular future does not? [p.14]

I think most major religions of the world – Christianity included – offer some points of view that we could claim are sacred, profoundly holy, and therefore worth revering and saving. So, in my opinion, Christianity does have the opportunity to offer a profoundly religious purpose to our reason for living that a completely secular future does not. Both points of view, however, are important – i.e., we ought not to eliminate one at the expense of the other. I do believe, however, that there is wisdom in keeping the church and state separate – even while each can continue to inform and affect the other.

Part II – Stating the Problem

4. Have you ever done something that had consequences far beyond those you envisioned? [p.19]

Yes, certainly. I chose to move from an island in the Caribbean to California after graduating from high school. I became an officer in the Marine Corps. I got married. We decided to have children. We moved from Virginia to California. I became a counselor and secondary school teacher. We moved from California to North Carolina. I chose to enter seminary and achieved a master’s degree in theology. We moved back to California. I was ordained in the United Methodist Church. Shall I go on? With every decision, with every move (both physically and psychologically), all kinds of things happened that I hadn’t envisioned – some deeply troubling, however most were surprisingly fulfilling. Throughout it all, the journey has been far more important than any single destination I’ve had along the way.

5. “No one can escape from their own frame of reference.” Comments? [p.24]

This is true. In the context of this book, Spong is correct here when he says that “biblical explanations inevitably reflect the worldview of the first century.” One cannot assume a “frame of reference” that is not his or her own – especially when that framework is separated by over two millennia from the present day. Thanks to the advances in the sciences, we know a whole lot more about the nature of reality than did those people in the first century of the common era. So, one of my favorite quotes in this same paragraph is where Spong says, “Biblical literalism thus quickly becomes biblical nonsense.”

What is also true, though, is that the families and cultures in which people have been raised have profoundly affected the ways that they come to view their world – be they families and cultures from the Ancient Near East or the San Francisco Bay Area of California. That’s not to say that we can’t (in fact, we should) begin to understand and appreciate the worldviews of others. It’s the only way we might be able to finally overcome the kind of tribalism that has created such enmity between people – across those thousands of years, across vastly different cultures, or even the kind of enmity that arises within the same country and culture (e.g., witness the deep divisions that we now see in the United States itself that have been created between people who hold significantly different political points of view).

6. How would you describe “the Christ experience”? [p.25]

Those people who were profoundly affected by the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth became convinced that he – in deeds and in fact – was the long-waited-for Messiah spoken about in Jewish prophecy. That title in Hebrew literally means “Anointed One” – which was then translated into the Greek as “Christos,” or Christ. While history, tradition, and subsequent Christian cultures have since given that title to mean “God’s chosen one,” originally it just meant “useful.” Isn’t that interesting? It might be fascinating to ponder that ancient meaning alone as it might apply to this Jesus of Nazareth. In modern Greek, though, “Christos” means “ethical,” “righteous,” “good,” “just,” “upright,” “virtuous” – and all other such synonyms. That’s where I would draw my “Christ experience.”

To begin with, for me, “the Christ experience” does not mean that in this man Jesus we see God fully revealed. Jesus was not nor ever “became” divine – no matter how the Church came to create that label for him. What’s more, the doctrine of the Trinity just obfuscated and deepened the confusion of who this man was. So, if I were to describe “the Christ experience” at all, I simply would use all of those words above from the modern Greek – in Jesus of Nazareth you would’ve seen them all, and more. I would not give the experience the elevation, then, that Judaism gave to the term “Messiah,” nor would I give it its early Christian equivalent title “Christ.” In my opinion, the result of doing that has been to obscure the remarkable life and teachings of that humble itinerant rabbi named Jesus – a Greek derivation of the name which, oddly enough, wasn’t his actual name anyway; his name would’ve been pronounced Yeshua, which itself, is a derivation of the Hebrew name Joshua. Let’s listen to this man, then, ponder how he seemed to live out his life, and begin to look at him in a completely new way. That would be a revolutionary “Christ experience” worth having.

7. Which thesis do you think is most significant? [pp.26-29]

If you mean by “most significant,” in order of importance, then I think that we ought start at the point where all of this started and get rid of #2 – “Jesus as the incarnation of the theistic deity.” Without that, everything changes! You then should be able to fully reclaim his humanity, thus also taking away #4 (the virgin birth), #5 (someone who does miracles), #6 (the need for sacrificial atonement ), #7 (the need for Easter) as well as #8 (a bodily ascension). Bring the man back to earth! Please!

Part III – Thesis 1: God

8. Describe your alternative to theism? [p.38]

I remain curious about what’s historically been referred to as “monistic monotheism” – more recently it’s become known as “panentheism” (note, not pantheism). Depending upon who you talk to, it’s been described as thinking of God as that Mystery which is greater than the universe and yet includes and interpenetrates it all. In other words, the universe is part of God, but not all of God. So, God exists inside of everything, but is at the same time, transcendent of everything. In some ways, you may view this concept of God as the Prime Mover of all that is. In the final analysis, God is not a being, but an ineffable Mystery. There is just something powerfully Sacred about this concept which, I admit, I don’t seem to be able to let go of.

9. How do you resolve the differences presented by the Bible and evolution? [p.47]

They cannot be resolved because, in this specific instance, the Bible and its theory of creation is mythic fiction. The theory of evolution is based upon sound scientific observation.

I also would take issue with what Spong calls “the work of God” there – that it’s “to bring about human completeness or wholeness.” Nope. That’s up to us – always was and always will be. In the final analysis, there is no theistic deity somewhere “out there” or even hovering around “everywhere” ready to assist or rescue us from ourselves. If we’re going to survive and evolve, it’s going to be up to us to figure out how to do it.

Even so, I still hear people mumbling in prayer, “God help us!” But you might as well call the “Ghost Busters” – and you might get more help from them!