This bookstudy will begin July 10, 2022 only on Zoom.

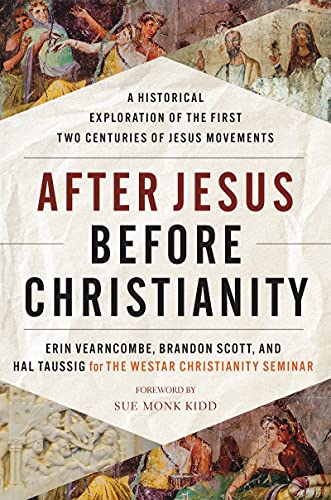

From the creative minds of the scholarly group behind the groundbreaking Jesus Seminar comes this provocative and eye-opening look at the roots of Christianity that offers a thoughtful reconsideration of the first two centuries of the Jesus movement, transforming our understanding of the religion and its early dissemination.

Christianity has endured for more than two millennia and is practiced by billions worldwide today. Yet that longevity has created difficulties for scholars tracing the religion’s roots, distorting much of the historical investigation into the first two centuries of the Jesus movement. But what if Christianity died in the fourth or fifth centuries after it began? How would that change how historians see and understand its first two hundred years?

Considering these questions, three Bible scholars from the Westar Institute summarize the work of the Christianity Seminar and its efforts to offer a new way of thinking about Christianity and its roots. Synthesizing the institute’s most recent scholarship—bringing together the many archaeological and textual discoveries over the last twenty years—they have found:

- There were multiple Jesus movements, not a singular one, before the fourth century

- There was nothing called Christianity until the third century

- There was much more flexibility and diversity within Jesus’s movement before it became centralized in Rome, not only regarding the Bible and religious doctrine, but also understandings of gender, sexuality and morality.

Exciting and revolutionary, After Jesus Before Christianity provides fresh insights into the real history behind how the Jesus movement became Christianity.

And, it's really easy to read.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Week 9 Questions

1 – How much of what you read “is about practice and not philosophy or theology”? (by %) 305

2 – How do you reconcile Jason BeDuhn’s quote on pg. 307 with my copy of his book “The First New Testament Marcion’s Scriptural Canon” containing the Gospel of Luke and 10 letters of Paul?

3 – What texts in particular do you “expect[] to cooperate in the production of meaning”? 309

4 – Has the word processor returned fluidity to writing that was removed by the printing press? Comments? 310

5 – Stratonike’s memorial makes it sound as though deification is like “going to heaven” when one dies. Comments? 313

6 – What difference, if any, did pgs. 314-5 make to your understanding of the Gospel of Mark?

7 – What is one thing that you had to “unknow” after reading this book? 319

8 – Have you ever tried to imagine what would be going on in your head if you lived 2000 years ago? Comments? 325

9 – What are your concluding comments on this book?

Responses to Week 9 Questions

Chapter 19: Better than a New Testament? (pp. 303-317)

1. How much of what you read “is about practice and not philosophy or theology”(by %)? (p.305)

Since I consider orthopraxy far more important than orthodoxy, I’m always looking for how a religion expects its followers to live, and much less so about the concept(s) of its deity. So, in the end, in almost all of my reading of such literature, I’m spending 95% of my time searching for what the authors have delineated as to how one should behave, not on how or what one should believe.

Let’s be clear, however, sometimes it’s about all three: practice, philosophy and theology. Two of my favorite quotes come to my mind in that regard:

He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God?

[Micah 6: 8 - NRSV]

I call heaven and earth to witness against you today

that I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses.

Choose life so that you and your descendants may live....

[Deuteronomy 30: 19 - NRSV]

2. How do you reconcile Jason BeDuhn’s quote on pg. 307 with...his book The First New Testament Marcion’s Scriptural Canon - containing the Gospel of Luke and 10 letters of Paul?

BeDuhn is just reconstructing Marcion’s text and exploring its impact on the study of Luke/Acts (a.k.a. the “two-source theory” or the “Q hypothesis”). He’s saying “Scriptural Canon” there as it’s traditionally been labeled – i.e., he doesn’t say that he, himself, would call it scripture. He’s simply presenting what he considers to be a methodologically sensitive treatment of Marcion’s significance. After all, BeDuhn is Professor of the Comparative Study of Religions; and yet I don’t know that he’s ever called himself a “religious” person.

3. What texts in particular do you “expect...to cooperate in the production of meaning”? (p.309)

I think that “the production of meaning” about how we should interpret the life and teachings of Jesus would be enhanced by further consideration of the ways in which he is presented in the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Mary.

In his book, "The Gospel of Thomas: The Hidden Sayings of Jesus," Marvin Meyer points out that it “belongs to a rich heritage of sayings collections” attributed to Jesus (p.9). He also says:

“The value of the Gospel of Thomas as a primary source for the

Jesus tradition is underscored by the presence within Thomas of

sayings of Jesus not included in the New Testament and sometimes

totally unknown prior to the discovery of this gospel” (p.14).

I have found two of these sayings to be extraordinarily important to me:

#70 – “Jesus said, ‘If you bring forth what is within you, what you

have will save you. If you do not have that within you, what you do

not have within you [will] kill you.’” (p.53)

That sounds a whole lot like the invitation to us outlined in Abraham Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” – the achievement of “self-actualization”(see my responses for Week 6, question #4). We should all learn that lesson.

And then there’s this one:

#113 – “His followers said to him, ‘When will the kingdom come?’

‘It will not come by watching for it. It will not be said, ‘Look, here

it is,’ or ‘Look, there it is.’ Rather, the father’s kingdom is spread out

upon the earth, and people do not see it.’” (p.65)

Shockingly, that’s as true now as it was two millennia ago.

As Meyer recognizes in his conclusion, “Between Jesus and any Christianity, at least a generation of silence intervenes” (p.119).

And even though about half of the Gospel of Mary is probably lost to us forever, it’s extraordinary insights, I think, are well worth our consideration. As Karen King has presented in the opening pages of her book The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle:

“This astonishingly brief narrative presents a radical interpretation

of Jesus’ teachings as a path to inner spiritual knowledge; it rejects

his suffering and death as the path to eternal life; it exposes the

erroneous view that Mary of Magdala was a prostitute for what it is –

a piece of theological fiction; it presents...the legitimacy of women’s

leadership; it offers a sharp critique of illegitimate power and a

utopian vision of spiritual perfection; it challenges our rather romantic

views about the harmony and unanimity of the first Christians; and it

asks us to rethink the basis for church authority. All written in the

name of a woman” (pp.3-4).

Those sayings of Jesus from Thomas, along with all of these revelations about Mary, would go a long way toward helping us “in the production of meaning” of who Jesus actually was.

4. Has the word processor returned fluidity to writing that was removed by the printing press? Comments? (p.310)

I’m assuming that by “word processor” you’re referring to the computer program that helps us with input, editing, formatting, and output of text. While that does allow us to store documents for future reference, that it has special editing tools (like spelling and grammar checks), that it gives us different kinds of fonts, and it makes it easy to insert or replace words and phrases without affecting the neatness of a document, it does not, however, automatically make our writing more flowing. You can have all of that stuff and still be a lousy writer.

As our authors point out (okay, somewhat facetiously):

“...it is clear that members of the many different Jesus movements

gathered almost exclusively at festive meals. Discovering now that

their ‘writings’ were not books for intellectuals matches well with

the activities of their boisterous banquets” (p.311).

5. Stratonike’s memorial makes it sound as though deification is like “going to heaven” when one dies. Comments? (p.313)

The apotheōsis (Greek for “elevation to the status of a god”) here is a cultural phenomenon – implying that some individuals are so revered in this life that they cross the dividing line between gods and human beings. The operative phrase used here for Stratonike on her monument, is that she “was blameless by all people during her life-time,” so is worthy of this honor. It doesn’t, however, imply some kind of spiritual elevation into a mythical heaven.

6. What difference, if any, did pgs. 314-5 make to your understanding of the Gospel of Mark?

No difference at all, really. I agree that it was “a way for members of Jesus associations to remember him and respond to a situation of absence” (p.314). He was gone, and his followers felt lost. That moved them to create stories out of their various memories of him, so that he might live on among them. As our authors go on to say,

“The ‘thing’ that is the Gospel of Mark is the thing that happens

when the actual community’s time together adds to and redoes

the stories” (p.315).

As our authors, again, remind us, in the original copy of Mark...

“There is no validating presence of the risen Jesus in this textual

object. Both content and composition in this story make Jesus’s

absence palpable” (p.316).

It’s a memorial that led to Jesus’s own apotheōsis – but, unfortunately (led by Emperor Constantine and the “early Church fathers”), later generations took it literally and made him into a god.

Chapter 20: Conclusion (pp. 318-326)

7. What is one thing that you had to “unknow” after reading this book? (p.319)

I can’t think of a single thing, really. It just brought back together the threads of what I was taught while I was in seminary at Duke. Because I disagree with the authors’ conclusion that there was no such phenomenon as Gnosticism, I don’t “unknow” a premise that I simply disagree with.

8. Have you ever tried to imagine what would be going on in your head if you lived 2000 years ago? Comments? (p.325)

Yes, but if I had a functional time machine, I’d never choose to exist during that era.

9. What are your concluding comments on this book?

“We must continue to listen for these buzzing, urgent voices.

These voices can and need to reshape our understanding of

group experience and belonging in the two vibrant centuries

after Jesus, before Christianity” (p.326)

I would respond to these last two sentences by simply saying, Amen! May we make it so.

Week 8 Questions

1 – Have you experienced (first or second hand) any kind of spirit possession? Comments? 268

2 – What other parable(s) of Jesus do you find with a similar hidden transcript to the legion of pigs? 271

3 – Extra Credit: What can you say about the connection between Roman violence and the various evil spirits mentioned in the non-canonical writings we have been reading (about)? 272

4 – Does the idea of Revelation being a song by a singer change your understand of it, and if so, how? 276

5 – How do you feel about yourself as you read The Thunder Perfect Mind? 281

6 – Why do you think martyrdom has faded away from modern Christianity? 286

7 – What is the modern equivalent to the “suffering self”? 292

8 – What would be your most important “I AM…” statement? To what are you most interested in belonging? 295

9 – If the gladiator performed empire, what did Jesus perform? Compare the honor of each. 297

10 – What do you think about the replacement of physical suffering with modern economic suffering and death (perhaps bankruptcy)? Is this an improvement? 301 Are we honoring a different god?

Reply to Week 8 Questions

Chapter 17 (supplementary questions)

1. Have you experienced (first or second hand) any kind of spirit possession? Comments? (p.268)

I have never been “possessed” by the spirit in the way that such “possession” has been traditionally described, nor do I know someone who has – i.e., as if such an individual spirit had taken over my mind and/or body (whether one claims it to be God or some other kind of spirit).

I have, however, been overwhelmed with emotion by awe-inspiring or beautiful experiences that I would claim were deeply spiritual experiences – many times. At some of those times, I’ve even felt that I’ve been in the presence of God – but nothing like the anthropomorphized deity that’s been portrayed in the Bible. These experiences have touched me with a variety of feelings: of wonder, reverence, joy, ecstasy, empathy, tenderness or communion. I’ve learned to stop and pay attention to them – to simply be still and rest in awe during those moments. They remain precious to me.

2. What other parable(s) of Jesus do you find with a similar hidden transcript to the legion of pigs? (p.271)

In a way, all of Jesus’s parables have a “hidden transcript” – where he speaks of things in this life that are actually meant to be symbols for a deeper, spiritual, reality. Some obvious examples might be the parable of the treasure hidden in a field (Matthew 13: 44). The word translated as “treasure” here, in Greek (thẽsaurós or θησαυρῷ), could literally mean “wealth” of any kind, but Jesus is referring to something else – Matthew is reporting to us that he meant the Kingdom of God (elsewhere also referred to as the Kingdom of Heaven). He then goes on to present another of Jesus’s parables, the one about the “pearl of great price” (Matthew 13: 45-46); it, too, is meant to be a symbol for the realm of God. Much the same is going on in the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15: 11-32) or the parable of the Sower (Mark 4: 3-9, Matthew 13: 3-9, and Luke 8: 5-15). All relate to a profound spiritual truth wrapped in what seems like a simple story. That’s the essence of a parable.

I could go on. There are more than 50 recorded parables of Jesus in the New Testament alone – some are duplicated, while others appear only once. Regrettably, people who remain completely unaware of spiritual things will never understand the deeper truths that Jesus was presenting in his parables. They neither have the ears to hear nor the eyes to see (By the way, Jesus is actually quoting Isaiah 6: 9-10 when he says this – cf. Mark 4: 10-12, 33, Matthew 13: 10-17, 34-35 and Luke 8: 9-10).

3. Extra Credit: What can you say about the connection between Roman violence and the various evil spirits mentioned in the non-canonical writings we have been reading (about)? (p.272)

Tragically, throughout human history, there is every bit as much evil perpetrated by people as there is goodness – but you can’t blame “demon possession” or “evil spirits” for such evil (unless the perpetrator were to be certifiably insane). In the end, as our authors point out:

“There is no single guiding story against violence. We find instead

creative commitments to difference and to communal strength

through challenging times” (p.275).

With the scourge created by people like Vladimir Putin or Donald Trump, such “challenging times” are as present, now, every bit as much as they were two millennia ago.

4. Does the idea of Revelation being a song by a singer change your understand of it, and if so, how? (p.276)

I don’t know where our authors came up with that analogy, but I do know that the Book of Revelation has more in common with the Book of Daniel than it does anything else in the New Testament. Both are apocalyptic literature – a kind of prophetic writing that first developed in Jewish culture after the Exile, but then became popular among, so-called, millennialist Christians. It’s just a kind of literary genre supposedly foretelling supernaturally inspired cataclysmic events that will happen at the end of the world.

I don’t know how one might even hum that tune.

5. How do you feel about yourself as you read The Thunder: Perfect Mind? (p.281)

I find myself feeling glad that I have devoted most of my adult life in opposition to bullies of all sorts – the kind who dishonor and afflict someone such as this woman who speaks with a divine feminine voice. No one should have to experience such humiliation and violence – for any reason.

Chapter 18: Romancing the Martyr (pp. 285-302)

6. Why do you think martyrdom has faded away from modern Christianity? (p.286)

The simple answer is that “modern Christianity” at least is no longer insisting upon the physical death of those it continues to label as heretics. People continue to be shunned and separated from their communities in other ways, however. Without physical, emotional, and communal support, sadly, many continue to experience a different kind of death today.

7. What is the modern equivalent to the “suffering self”? (p.292)

I’d say it would be the person who would always “do the right thing” in the face of powerful opposition and so often experiences profound personal suffering because of it. But, as our authors point out, such a life is not a requirement; it is a choice. Too few of us, sadly, have the courage of our convictions to choose to live such a life.

It reminds me of what the prophet Micah spoke of (in 6: 8) – and here’s my translation:

“What does the Lord require of you? Do justice. Act with loving

kindness. And show some humility in whomever you’ve decided

your image of God might be.”

We could use more people who follow that kind of trinity.

8. What would be your most important “I AM…” statement? To what are you most interested in belonging? (p.295)

“I am the Way, the Truth and the Life” – and whether or not Jesus did say it exactly that way, he wasn’t making some kind of declaration that he was God come down to earth. He was trying to show his people what kind of life they should choose to live – as he had tried to do. It was a life of compassion shown toward those who were suffering, a life of loving kindness instead of self-centeredness, a life that spoke truth to power no matter what the consequences – a life that all of us are meant to live if we would have the courage to do so. Even as I have fallen short of living such a life, it is the one that I still desire to belong to.

9. If the gladiator performed empire, what did Jesus perform? Compare the honor of each. (p.297)

The majority of gladiators never “voluntarily” chose to fight because most of them were slaves. Even those few who were freemen, it was their job to appear in the arena – they had a contract and a manager; but they either fought or they were killed. Any “performance” of empire was the demonstration of powerful men showing off their prowess by killing those who were weaker. If we feel, as I do, that there was no honor or virtue in that, still, it was the “Roman Way.”

The greater honor was exemplified by Jesus who showed compassion toward the weak and disenfranchised, who acted with loving kindness, and spoke truth to power. His life was a supreme example of a different kind of empire – the Empire of God.

10. What do you think about the replacement of physical suffering with modern economic suffering and death (perhaps bankruptcy)? Is this an improvement? (p.301) Are we honoring a different god?

Wherever suffering or premature death continues to be accepted as “just the way things are,” our modern-day empires are no better than ancient Rome’s. In this we are “honoring a different god” than the One revealed by Jesus of Nazareth. While the empires of today (including our own) may not appear as blatantly cruel as ancient Rome’s, they are more powerful, so the devastation and suffering that they have created is greater, now, than it’s ever been. The longer that it continues, the more meaningless, sadly, the life and teachings of people like Jesus or Gandhi seem to become.

Week 7 Questions

1 – How do you feel about Paul’s claim of “superior intimacy with the Anointed through his personal call”? Does Paul get more standing than Jesus’ students because of his call? 232

2 – Why do you think Paul “disappeared” for a century? 233

3 – What are the dates of Clement, Ignatius and Polycarp? 235

4 – “how much of early writings are lost”? Make a wild guess at the percentage. 237

5 – Without books like AJBC, do you see the contradictions between the Acts of the Apostles and Paul’s own letters? 240

6 – What struck you as particularly interesting in the pro / con discussion of Paul? 245

7 – Describe your awakening of gender in today’s world. How much effect have our assorted books made? 250

8 – Do you see elements of Gnosticism in the Gospel of Mary? (Is this a fair question?) 254

9 – Why do you think it was Jesus, out of many thousands of crucified peasants, who was the basis of what became Christianity? What combination of things went into the development of the myth? 255

10 – Which of the images of Jesus: True Human, Rescuer, Parent, Noble Death, Enslaved Savior, Spiritual Body or Anointed lord do you like best? Why? 282

11 – you may want to add other names to your answer to #3 above. As I grow to understand the development of Christianity, it helps me see where in time various authors are active.

Responses to Week 7 Questions

Chapter 15: Paul Obscured (pp. 232-246)

1. How do you feel about Paul’s claim of “superior intimacy with the Anointed through his

personal call”? Does Paul get more standing than Jesus’ students because of his call? (p.232)

Well, whether it was sun stroke, a seizure, or a genuine spiritual experience as outlined in Acts (9: 1-19 and retold in Acts 22: 6-21), in his former life – as Saul the Pharisee – he was large, in charge, and very much in control of his world. Being struck blind, and then not eating or drinking for three days, might cause hallucinations for almost anybody. Would such an experience give him the right to claim “superior intimacy with the Anointed” because of it? I think not. And yet like many who’ve persecuted others earlier, but turned their lives completely around (e.g., the slave trader who’s reputed to have written the beloved hymn “Amazing Grace” after his conversion), the new Saul, now Paul, experienced the nearest thing to a resurrection that any human being can have. But, again, it doesn’t make him worthy of greater standing in the community. That kind of conclusion has led to some awful misuses of power – witness just such awful history exhibited by popes, bishops and other ambitious and self-righteous clergy.

2. Why do you think Paul “disappeared” for a century? (p.232)

I think our authors answer that question on the next page:

“Writings in the ancient world did not have the wide distribution and

circulation that they have today, and this was especially true of letters

that were not composed with a larger audience in mind” (p.233).

3. What are the dates of Clement, Ignatius and Polycarp? (p.235)

The writings of these so-called Apostolic Fathers are particularly informative because they speak of what they considered to be dangerous administrative and doctrinal deviations that were going on twenty to forty years after the Church lost Peter and Paul. Doctrine during this time was chaotic and wouldn’t stabilize into something like orthodoxy until the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE.

Clement (c. 35-99) is known to have been a leading member of the church in Rome during the late 1st century and was bishop there from 88 to 99 CE.

Ignatius (c. 35-110) became the bishop of Antioch in c. 107 CE and died a martyr in Rome.

Polycarp (c. 69-155) was bishop of Smyrna and also died there – another Christian martyr.

4. “...how much of early writings are lost”? Make a wild guess at the percentage. (p.237)

Since much of that culture was illiterate, it may not be as much as you might think. Again, as our authors pointed out (and I mentioned above in #2):

“Writings in the ancient world did not have the wide distribution and

circulation that they have today, and this was especially true of letters

that were not composed with a large audience in mind” (p.233).

My completely uninformed guess, then, would be that we lost, at most, only 20% of writings from those who considered themselves followers of Jesus.

5. Without books like AJBC, do you see the contradictions between the Acts of the Apostles and Paul’s own letters? (p.240)

Well, I have the benefit of a seminary degree in this stuff, so many of the contradictions were pointed out to me while I was at Duke – especially in my Koiné Greek and New Testament studies. Like most of these writers, the author of Luke/Acts had his own point of view to promote and defend.

6. What struck you as particularly interesting in the pro/con discussion of Paul? (p.245)

What struck me as particularly interesting were the ways in which Marcion used much of Paul’s writings as sacred “scripture.” I had no idea that, as our authors point out:

“Outside of Marcion’s circles those who want to make room for Paul

value him as a legendary founder of non-Judean communities...[but]

not as a theologian. ...only Marcion shows much interest in Paul as a

theological witness” (p.247).

We know, of course, that Marcion was dismissed by the early “church fathers” as a heretic. So, “Paul was controversial in his own day and [has] remained so” (p.246) – in many ways he still is today.

Chapter 16: Jesus by Many Other Names (pp. 247-264)

7. Describe your awakening of gender in today’s world. How much effect have our assorted books made? (p.250)

While I had my suspicions as a youth, my real “awakening” to the broad spectrum of gender actually happened while I was working on my Masters Degree in Counseling Psychology at Santa Clara University (ironically, a private Jesuit university!). Human sexuality, finally, is not just a binary heterosexual/homosexual matter; it’s every shade and nuance in between. What’s more, one can be both masculine and a feminist at the same time. I am, myself. After millennia of male dominance, we should, finally, work to establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of all genders. Women have been treated unjustly for far, far too long – but then so have others on that full spectrum of human sexuality between men and women.

This “enlightenment” (you might say) of mine was also around the time when in 1973 – as a result of extensive scientific research – the American Psychiatric Association (APA) declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder. Prior to that – beginning with their first edition in 1952 – the APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) had classified homosexuality as just that, a mental disorder. It’s taken a long, long time to break down the “good old boy” networks in our culture about such things as this – and we still have much work to do.

So, I can’t say that our “assorted books” have had that much effect on my conclusions about gender – except to affirm what I already suspected or knew from my own studies and life experiences.

8. Do you see elements of Gnosticism in the Gospel of Mary? (Is this a fair question?) (p.254)

I do not. There’s nothing in this wonderful gospel claiming that some people have been given “secret knowledge” (γνώσεις or gnosis) by God while others have not: that’s Gnosticism in a nutshell. Mary’s insight into the ultimate spiritual value of both the soul and the mind keeps in balance the kinds of insights that we get from our intuition as well as from the methods of science. If there is any hint of gnostic thinking in this gospel, it might be how our gender (our “outer garment”) distorts the true image of the soul. However, I don’t see this gospel as bifurcating the two, but actually encouraging an ongoing dialogue within and between our body (mind) and our spirit.

What’s more, the Gospel of Mary invites us to not just be male or female, but be in touch with aspects of both genders within our own sense of self. In a very real way, this gospel invites us to see how we might become a true – and so complete – human being. For its time, it was an extraordinary hypothesis.

9. Why do you think it was Jesus, out of many thousands of crucified peasants, who was the basis of what became Christianity? What combination of things went into the development of the myth? (p.255)

I think that he was a particularly gifted and charismatic storyteller that just touched the longings and imagination of his people. In that vein, our authors note:

“The parables of Jesus, as characteristic of Jesus’s style of teaching

...come as close to Jesus’s perspective of himself as we can reasonably

get” (p.247).

What’s more,

“...his death resulted in stories and songs of hope, inspiration, and a

commitment to remembering him throughout the Mediterranean area.

People who needed an expression of their own devastation found

stories of Jesus filling those needs. ... Jesus’s story gave them hope

when no end to the suffering was in sight” (p.255).

PART IV – FALLING INTO WRITING

Chapter 17: Hiding in Plain Sight (pp. 267-284)

10. Which of the images of Jesus: True Human, Rescuer, Parent, Noble Death, Enslaved Savior, Spiritual Body or Anointed Lord do you like best? Why? (p.282)

If I were to choose only one from this list, the image of Jesus that I like best would be “True Human.” To me, he just personifies that peak of maturity exemplified by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs described as “self-actualization” (See my answer to question #4 of Week 6 above). Jesus was a supreme example of what it must mean to be a fully developed human being – exhibiting all of the skills, compassion, love and courage that we should all aspire to have. He shows us the way, the truth, and the life (even though he probably didn’t say that about himself as John 14: 6 claims that he did). I think that his contemporaries experienced that about him, so the legends began from there and grew into all of the stories and scripture that we now have about him.

11. You may want to add other names to your answer to #3 above. As I grow to understand the development of Christianity, it helps me see where in time various authors are active.

I might add Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260-339), a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist who became the Eastern church bishop of Caesarea in c. 314 CE. While he created a ten-volume work purporting to be the history of Christianity, he wasn’t a very good historian (He knew next to nothing about the Western church.). His historical works are really apologetic – i.e., showing by “facts” how the Church had vindicated itself against heretics and heathens. Curiously enough, however, he was one of the key proponents of Arianism – the doctrine that claimed Jesus was not the same substance as God – and eventually became the leader of an Arian group that came to be called the Eusebians.

Unfortunately, he also described the Emperor Constantine as a “model Christian” and “most beloved by God,” so, in his day, he was as much a maker of history as he was a recorder of it. Still, he was a fascinating guy.

Week 6 Questions

1 – Do you recall when you first realized you were a heretic? Comments? 202

2 – (How) Has your participation in our book study changed the way you relate to others at church on Sunday? 205

3 – How does our current education system teach “control of the passions”? Does it do a good job now? Did it 2000 – 2500 years ago? 205

4 – What do you think about salvation as defined by self-control? 209

5 – While the story of Thecla is obviously legendary, do you think there was a real person behind the legend? 213

6 – So is there, or is there not, Gnosticism? 219

7 – What is another word that is not a “thing” but because it is a word, we use it to think with? 220

8 – How does changing the word Gnostic to something else make any difference? 225

9 – There was a great deal of power associated with producing orthodoxy, and none associated with Gnosticism. What difference does (did) this make? 225

10 – Now that our authors have demolished Gnosticism, what difference does that make to you? 230

Responses to Week 6 Questions

PART III – REAL VARIETY, FICTIONAL UNITY

Chapter 13: Inventing Orthodoxy Through Heresy (pp. 199-215)

1. Do you recall when you first realized you were a heretic? Comments? (p.202)

I knew that I was a heretic when I was 12 years old — I just didn’t know that you called it that. I always felt like “the odd kid” in my Sunday school classes because of this. In one form or another (by both my peers and some adults) I was told, “But, Doug, y’ just gotta believe!” But that never ever worked with me. I needed other options. And I got them.

2. (How) Has your participation in our book study changed the way you relate to others at church on Sunday? (p.205)

Sadly, I just wouldn’t feel right being there. Not only have I been uncomfortable with much of the patterns of the worship itself, it might even undermine the role of the pastor because my theology would be in opposition to significant traditional (i.e., orthodox) parts of the liturgy.

3. How does our current education system teach “control of the passions”? Does it do a good job now? Did it 2000 – 2500 years ago? (p.205)

I think that we still struggle with this every bit as much as they did twenty millennia ago. As a former classroom teacher, I can say that “control of the passions” was always a key part of my first six-week’s lesson plan at the beginning of every year. I never told my students about it but, for myself, I titled it “How to Behave Like a Human Being.” I would talk, we would discuss together, and they would write about what “good manners” meant. We would also talk in class about the issues of bullying in school – of why it happened and what to do about it. I would often remark to other teachers during our off-period, how sad it was that kids didn’t seem to learn these things at home; so I had to teach them all about it in my own classroom.

I wish that I’d had Robert Fulghum’s book back then: "All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten: Uncommon Thoughts on Common Things" (©️ 1986). I would’ve used it. These are the things that he learned:

• Share everything.

• Play fair.

• Don’t hit people.

• Put things back where you found them.

• Clean up your own mess.

• Don’t take things that aren’t yours.

• Say you’re sorry when you hurt somebody.

• Wash your hands before you eat.

• Flush

• Warm cookies and cold milk are good for you.

• Live a balanced life – learn some and think some and draw and paint and sing and dance and play and work every day some.

• Take a nap every afternoon

• When you go out into the world, watch out for traffic, hold hands, and stick together.

• Be aware of wonder. Remember the little seed in the Styrofoam cup: The roots go down and the plant goes up and nobody really knows how or why, but we are all like that.

• Goldfish and hamsters and white mice and even the little seed in the Styrofoam cup – they all die. So do we.

• And then remember the Dick-and-Jane books and the first word you learned – the biggest word of all – LOOK.

As Fulghum points out, “Everything you need to know is in there somewhere. The Golden Rule and love and basic sanitation. Ecology and politics and equality and sane living” (pp.6-7). I agree.

4. What do you think about salvation as defined by self-control? (p.209)

I prefer “salvation” to be a state of being that the renowned psychologist, Abraham Maslow, called “self-actualization.” That’s the closest thing to “salvation” in this life that I can think of. And forget about what might or might not happen after we’re dead – that shouldn’t figure in at all on how we live in the here-and-now. Maslow’s self-actualization would be considered to be at the top of what he called our “hierarchy of needs.” It’s a theory of motivation that claims that anybody’s behavior is actually only dictated by his or her place within these five categories:

1.) physiological needs: all of those things that are the biological requirements for human survival (e.g., clean air, food, water, shelter, clothing, warmth, sleep, et al.)

2.) safety needs (e.g., protection from the elements, security, order, law, stability, et al.)

3.) love and belonging needs: the first of every human being’s social needs (e.g., the desire for interpersonal relationships and being accepted as part of a group – to include friendship, intimacy, trust, acceptance, and the receiving and giving of affection and love)

4.) esteem needs: including self-esteem (which would come from having a sense of dignity, achievement, and a mastery of something so some measure of independence) and then the kind of esteem that one gets by achieving a reputation that leads to respect from others – it could also include some level of status or even prestige.

5.) self-actualization needs, then, would be finally realizing your full potential so that you have a sense of self-fulfillment – while still looking to have further personal growth and deeply meaningful spiritual experiences (i.e., what some might call “peak” experiences)

Acquiring all five of those – and, usually, in that order – will lead a person to feel healthy, happy and fulfilled. If you miss out on any one of the first four, though, you’ll never make it to #5. Getting all of these would be my idea of salvation and, at the last, finally becoming the kind of person that you were meant to be – that you could and should want to be.

While it’s a leap ahead in the text, I do like the conclusion that our authors reach later in Chapter 16. What’s more, it’s what we ought to work toward in this life – never mind the next:

“Salvation in the second century did not deal with God’s judgment

but was more readily conceived as an escape from fear, disease,

chaos, emotional torment, physical danger, and death” (p.259).

5. While the story of Thecla is obviously legendary, do you think there was a real person behind the legend? (p.213)

In spite of the stories of her miraculous powers (and, after all, Jesus was venerated in much the same way), anyone whose teachings lasted a lifetime, who was a well-known follower of Paul, who had hundreds (if not thousands) of followers, and then was publicly memorialized in stone – as Thecla was (see p.200) – must have been a real person.

Chapter 14: Demolishing Gnosticism (pp. 216-231)

6. So is there, or is there not, Gnosticism? (p.219)

Well, there are some biblical scholars who still would say that there was such a loosely organized religious and philosophical movement like this that flourished during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE (One notable such scholar is Elaine Pagels, the author of The Gnostic Gospels.). These movements all seemed to have at least one common element: a certain position of “anti-cosmic world rejection.” Adherents of this movement simply came to be referred to as “Gnostics” because they believed that some human beings were fortunate enough to hold a piece of the Divine within themselves (i.e., the “highest good” or “divine spark”) which somehow had fallen from the immaterial world into their bodies. That, supposedly, gave them a special kind of intuitive awareness of hidden mysteries (in Greek, γνώσεις or gnosis) – so, a special kind of knowledge in comparison to just ordinary analytical knowledge.

While there probably was no actual cult that called itself “Gnostics” during that time, I would say that it is a “thing” even though it may have been a category created by early biblical scholars (The 17th century English poet and philosopher, Henry Moore, is believed to be the one who first used the term.). After all, we’ve done much the same thing with the categories of “orthodox” and “non-believers” (therefore “heretics” and “atheists”), or “fundamentalists” and “progressives.”

7. What is another word that is not a “thing” but because it is a word, we use it to think with? (p.220)

How about that word “heresy?” It’s not a “thing.” It’s a choice. As I’ve been saying for quite a long time, it was the institutional Church that turned the very act of choosing into “a wrong belief.”

8. How does changing the word Gnostic to something else make any difference? (p.225)

It takes away the understanding that some people – unfortunately and mistakenly – have long believed that they’ve had some “secret” knowledge given to them by God. It was a mistake in the first two centuries of the common era; and it’s a mistake many often continue to make today.

9. There was a great deal of power associated with producing orthodoxy, and none associated with Gnosticism. What difference does (did) this make? (p.225)

If there is a difference, it’s in what we may have lost of the beliefs and teachings of those first two centuries. Our authors put it this way:

“These documents offer important information about the many

different Jesus movements, Wisdom schools, and adherents of

the Anointed in the second century” (p.224)

They still may not have made the canon or ever been considered orthodox, but at least we’d have had access to them to be able to make up our own minds – to be thoughtful and informed “heretics.”

10. Now that our authors have demolished Gnosticism, what difference does that make to you? (p.230)

I wouldn’t say that they “demolished” that early movement – which was just one reality among many of those first disparate Jesus groups – but it makes no difference to me, either way.

Week 5 Questions

1 – Can you recall what you first thought about Jesus renouncing his family? Are your ideas different now? 152

2 – What does “proper shame” mean on pg. 154, line 4?

3 – When we were studying Scott’s “The Real Paul” I suggested that you read Philemon. You may want to read it again after this chapter. What differences do you see now? 157

4 – Compare non father led families of this era to modern single mom households. 158

5 – How many clubs do you (or have you) belong[ed] to? What are important similarities and differences among them? 168

6 – What do you think are the most significant A) similarities and B) differences between today’s churches and the associations (of a religious nature) of Jesus’ time? 170

7 – Why do you think people of Jesus time took their meals reclining? 181

8 – Have you experienced anything like the exchange between Jesus and Salome? Comments? 182

9 – Have you participated in meals (banquets?) where those present were VERY different? 185

10 – How would you feel about the Prayer of Thanksgiving being offered before our final potluck? 187

11 – Why the decline in festive communal meals? 190

12 – When you bathe, are you conscious of washing off physical, moral, attitudinal and social “dirtiness”? Which ones? 192

Responses to Week 5 Questions

Chapter 10: Experimental Families (pp. 147-162)

1. Can you recall what you first thought about Jesus renouncing his family? Are your ideas different now? (p.152)

I never have seen this as a “renouncement” of his family. If, in fact, Jesus actually said something like this (Mark 10: 29-30, et al.) – and I remain unconvinced that he ever did – I’ve always read it as a way of saying that family loyalties should be transcended by his message of the gospel (“good news”). That overcomes everything – and, by that, I don’t mean the traditional orthodox substitutionary sacrifice of his life theory that supposedly “saves” us from our sin. I think that it means living a life of lovingkindness and justice in much the same ways that he did. Period.

2. What does “proper shame” mean on pg. 154, line 4?

In the context of that culture, it means behaving in ways that promote social cohesion within the family – in this case, whatever the paterfamilias says that behavior should be.

3. When we were studying Scott’s “The Real Paul” I suggested that you read Philemon. You may want to read it again after this chapter. What differences do you see now? (p.157)

I’ve not read Scott’s book, but I have read the one titled The Authentic Letters of Paul, (written and edited by Art Dewey, Roy Hoover, Lane McGaughy and Daryl Schmidt).

I think that our authors of After Jesus Before Christianity aren’t strong enough here. The burden of Paul’s argument is that the slave, Onesimus, is no longer what he was but is somehow very “special” to Paul and so should be even more so to Philemon – to see him...

“...not now as a servant, but above a servant, a brother beloved, specially

to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh, and in the Lord?” (v.16)

Paul also plays upon Onesimus’s probable nickname “Useless” by giving him the new nickname of “Useful” – alluding to the root meaning of Onesimus which means “useful” or “beneficial.”

We need to remember that slavery was intrinsic to the social pyramid of the ancient world. And yet what Paul believed God had done in Jesus led him to conclude that a new age had begun; a new world order was underway and that he, Paul, was an envoy of that new regime – where there is “no longer slave or freeborn.” Paul was asking Philemon to move beyond the established social assumptions of the first century and make a real step in the direction of true human freedom.

So, while Paul may have been an extraordinarily zealous Pharisaic Jew, he was able to experience a paradigm shift so profound that it literally transformed the way that he saw the world and everything in it. This is someone who glimpsed what it must mean to live beyond tribal or ethnic boundaries and imagined that those who once were considered to be outsiders could – and should – now be seen as equals. For its day and time, this point of view was absolutely extraordinary.

4. Compare non father-led families of this era to modern single-mom households. (p.158)

I really don’t see a comparison. Women like Chloe and Thecla led families because they rejected the paterfamilias model that denigrated women and denied them positions of equality next to the men of that era. They chose to strike out on their own. The single-mom households of today had no choice. They were abandoned – largely as the result of “dead-beat dads” who refused to share the role of parenting their own children and either just walked out or were forcibly incarcerated for breaking the law and then never came back.

Chapter 11: Join the Club (pp. 163-178)

5. How many clubs do you (or have you) belong[ed] to? What are important similarities and differences among them? (p.168)

I’ve chosen to accept the wide-ranging definition of a “club” which – according to my dictionary – is this: “a group of persons organized for a social, literary, athletic, political, or other purpose.” Given that broad understanding, I’ve been a member of a number of them:

• Church – first the UCC and now the UMC (a lifetime of active membership which began in Sunday School and youth fellowship, then continued on into my entering the ordained ministry)

• Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts & Sea Scouts (from childhood to my teenage years)

• numerous athletic leagues and teams (from track, tennis, soccer, softball, baseball, basketball & football during my youth and young adulthood, to table tennis, cycling, golf & bocce ball here in retirement)

• Theta Chi fraternity (as a university undergraduate)

• American Counseling Association (as a post-graduate)

• Secondary School teaching, coaching & counseling positions

• American Federation of Teachers (AFT)

• Swim & Racquet Club

• Divinity School (post-graduate degree in theology)

• Lions & Rotary Clubs

• Bridge Club

• Green Circle Program (e.g. https://greencircle604767361.wordpress.com/green-circle-outline/)

• B.A.S.K. – the Bay Area Sea Kayakers (fun + environmental activism)

• Spiritual Directors International

• Book Clubs (on theology, but also groups centered on social justice and anti-racism)

• Writers Group (sharing our creative side through our own poetry and prose)

While the central thread through them all might be socializing with like-minded friends, many of these “clubs” also involved activities that helped build a better community (i.e., made for a more kind, compassionate, egalitarian, just and – in the case of B.A.S.K. – even a cleaner one!)

6. What do you think are the most significant A) similarities and B) differences between today’s churches and the associations (of a religious nature) of Jesus’ time? (p.170)

I think that the “sense of belonging” (pp. 166 ff.) that both provide may be the most significant similarity. Secondarily, however, both also creatively provided a way to “get together.” As our authors point out, the Hebrew word בֵּית כְּנֶסֶת – or synagogue – literally first meant “a bringing together” (p.168). Only later did it actually become “a place of gathering” and so became associated with a building – in that sense, a modern-day church has a lot in common with today’s synagogue. Whenever we do just that – get together – we have a lot in common with those first communal associations which were the disciples and earliest followers of Jesus.

Other than the fact that there were no buildings set aside as gathering places because they met in people’s homes, I’d say that the most significant difference between then and now is the elaborate and strict hierarchy exemplified within today’s institutional Church. It didn’t exist in those 1st century gatherings. Establishing community seemed to be more important than any single individual (i.e., no clergy, so no bishops, cardinals or popes.).

Chapter 12: Feasting and Bathing (pp. 179-196)

7. Why do you think people of Jesus’s time took their meals reclining? (p.181)

I think, initially, it was just a sign of power and luxury enjoyed by the elite, but then was carried over into those further on down the social ladder. Anyone who could afford it, just copied this laid-back dining style.

Personally, I don’t think that it would help my digestion – at all.

8. Have you experienced anything like the exchange between Jesus and Salome? Comments? (p.182)

Yes, I have. It seems to me that at its heart, that interaction in Thomas 61 is about when a man and a woman both are enlightened about the presence and reality of God so become “filled with light.” In the unity of that moment, they “become one.” I have experienced sharing those kinds of moments in many small groups – even here in the Lutz book group. For me those moments are filled with deep emotion and a sense of blessedness. Ultimately, however, it transcends any sense of gender. We’ve both been caught up in a feeling of wonder, so rare, that we share in a kind of spiritual union. It has nothing at all to do, however, with whether one of us is male and the other female.

Separated from any such shared experience, all we might feel would be emptiness – “darkness.” And I’ve been there as well. But, again, this has nothing at all to do with one’s gender. It doesn’t matter whose son or daughter you are in this world; in the end, all that matters is that you experience yourself as a child of God.

As the scholars of the Westar Jesus Seminar pointed out, this theme of “light” runs all throughout the Gospel of Thomas (e.g. Thomas 11: 3, 24: 3, 50: 1, 83: 1-2) as well as this concept of unity as opposed to division (e.g. Thomas 11: 4, 22: 4, 106: 1). The exchange between Jesus and Salome here is reminiscent of the claim in Thomas 24: 3 that “there is light within a person of light” – i.e., that there’s something of God revealed in and through that person. Thomas talks a lot about that kind of “coming together” (see The Five Gospels, p. 507). The point is, either you are “filled with light” or you’re “separated from God” and, so, “filled with darkness.”

9. Have you participated in meals (banquets?) where those present were VERY different? (p.185)

Yes, I have. Oddly enough, they’ve often come at wedding celebrations where it’s become very clear to me that “these are not my kind of people.”

10. How would you feel about the Prayer of Thanksgiving being offered before our final potluck? (p.187)

While that prayer might have some redeeming features, I feel like it’s too anachronistic and paternalistic in its imagery for God. The only lines that I do find meaningful, though, are these:

“...if there is [any] sweet and simple teaching, it gives us mind, word,

and knowledge; mind that we may understand [God]; word that we

may interpret [God]; knowledge that we may know [God]” (p.186).

So, I expect that I’d “tune out” if this prayer were presented to our group as printed. My mind and heart would wander somewhere else – which wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing; I find myself doing it during many services of worship these days.

Besides, Evelyn absolutely can come up with a better one!

11. Why the decline in festive communal meals? (p.190)

People just don’t want to have to cook for pot-lucks that often. At most, they are happy to share cookies and a drink after worship services and chat with friends for a while – but they’re probably not talking about theology or the worship that they just experienced.

12. When you bathe, are you conscious of washing off physical, moral, attitudinal and social “dirtiness”? Which ones? (p.192)

When I bathe (and it’s usually by taking a shower), I’m just cleaning my body. That other step requires a different kind of “washing.” In my case, that only happens during times of deep reflection or meditation. If I do sense any kind of “dirtiness” at times like that, it probably would be dealing with any feelings of anger or resentment that I might be carrying.

Week 4 Questions

1 – It appears that Westar makes no distinction between canonical and non-canonical literature. What do you think about this? 104

2 – Today women get into leadership roles by copying men. Hod do you think our culture would differ if it were run by women, as women, and not as copies of men? 108

3 – Do you think there is any significance to the use of “sexual status or sexuality” rather than gender on page 112?

4 – Compare the handling of 1 Corinthians in as many sources where you have an interest. 114

5 – Did any of you have gender issues (that you want to share) in your life? I suppose these would occur in adolescence. 115

6 – How important is your gender in the definition of your identity? 120

7 – “resist, to keep living in a world of crushing opposition.” But no one except Antiochus lives. I don’t understand. Comments? 125

8 – If the question of whether the early movements of the Way were positive or negative toward women is the wrong question, what would you ask instead? 128

9 – If you were to make and identity statement as Paul did on pg. 135, what would you include?

10 - What do you think is the difference between belonging to the God of Israel and belonging to the Methodist (or Presbyterian) church? 139

11 – Can you give a better one sentence or phrase description of this chapter than their final “A Messy Blend”? 145

Responses to Week 4 Questions

PART II – BELONGING AND COMMUNITY

Chapter 7: Testing Gender, Testing Boundaries (pp. 99-114)

1. It appears that Westar makes no distinction between canonical and non-canonical literature. What do you think about this? (p. 104)

I don’t see where that is so. Westar has distinguished between the two or they wouldn’t have given the non-canonical texts so much attention. They have a place. They have a voice worth hearing – even if those who closed the Bible to them did not think so. The result is a whole new orientation with respect to the texts and the issue of just what constituted monotheism in Israel at the time of Jesus.

To clarify the terms: “canonical” refers to something that follows the law stated by the canon – i.e., the sixty-six books of the Bible as they’ve been published for millennia, first by Judaism and then by Christianity. A “non-canonical” translation means that it deviates from those general known rules of translation. So, the work of the Westar Institute and its scholars has suggested a number of new perspectives on certain issues (for example, the place and role of women within those earliest followers of Jesus). Westar has proposed an alternative paradigm for understanding what pre-Christian communities looked like and the diversity of beliefs that they held.

A significant conclusion in this chapter is stated on the next page:

“Women and men have equal rights to teach and to lead. This equal

right derives from a shared focus beyond gender: a focus on the

attainment of true, perfect human status” (p.105).

In the canonical book of 1 Timothy, on the other hand, no such egalitarian status exists; in fact, it’s just the reverse:

“Women in 1 Timothy are not authorized for anything except childbirth.

Women are to be invisible in public and in the activities of the community.

They are commanded to be silent” (p.107).

2. Today women get into leadership roles by copying men. How do you think our culture would differ if it were run by women, as women, and not as copies of men? (p.108)

I think that it’s an overgeneralization to conclude that women “get into” such roles simply by “copying men.” It may be true that women, at least initially, have stepped into well-established roles that have long been defined by men as they follow behind them. But, significantly, many women have been quick to present particularly feminine ways of redefining those roles that have been, for far too long, defined only by males. Does it mean that they’d do a better job? Not necessarily; they’d just approach it differently – and, yes, might even do it better. But they need a chance to do it.

Our culture could benefit from both women and men learning to adopt the historically positive attributes of another gender while, at the same time, refraining from the negative attributes that each has as well. Curiously enough, we’ve yet to determine the benefits and drawbacks of nonbinary ways of being – those remain vastly underrepresented in politics, business and the media.

3. Do you think there is any significance to the use of “sexual status or sexuality” rather than gender on page p.112?

If there is any significance, it’s used to point out the ways in which the culture of that era further denigrated women. As our authors point out there, “‘Woman’ was a status a person became.” Along with defining sexual “deviance,” as well as exactly how and when a girl became a woman, that male-dominated society even went so far as to determine what was to be the acceptable expression of a woman’s sexuality.

As far as “implications of transgressive sexuality” were concerned, apparently that culture (as with some cultures still today) regarded sex as dangerous territory that must be rigorously controlled, regulated, and subjected to strict rules. It led to the conclusion that any sexual acts that defied acceptable practices would be seen, in various ways, as defiling, immoral, even unnatural.

4. Compare the handling of 1 Corinthians in as many sources where you have an interest. (p.114)

Regrettably, I couldn’t access those papers that are listed there at the end as relevant to this chapter, but I would be interested in reading Joanna Dewey’s on how women of that era lost their “agency” and even their visibility.

I do agree with our authors’ conclusion:

“First Corinthians is just one example of contradictions at most,

ambiguity at best, within a single writing. Such ambiguity is often

found in studying and interpreting ancient writings, which have an

internal history and social situation that are not always apparent to

later readers.”

Such ambiguity and uncertainty, unfortunately, has led to some really bizarre doctrinal conclusions by the institutional Church.

Chapter 8: Forming New Identities Through Gender (pp. 115-129)

5. Did any of you have gender issues (that you want to share) in your life? I suppose these would occur in adolescence. (p.115)

The only “gender issue” that I confronted as a teenager had to do with the acts of violence perpetrated by male bullies – and my having to make “fight or flight” decisions when confronting them. I finally did come to the conclusion that doing one or the other did not define what “being a man” meant for me. In so many ways, confronting bullies of every sort actually came to be an integral part of my lifetime vocation – first, as an officer in the Marine Corps, then a teacher, coach, counseling psychologist, and finally a pastor.

6. How important is your gender in the definition of your identity? (p.120)

It’s very important to me, because I’ve redefined what I’ve felt “being a man” should mean in this day and age. For me, it begins with treating everyone with respect. Nobody should act in malicious ways toward others – for any reason. Being a “real man” should also mean knowing what to do if you are bullied, as well as standing up for others who’ve been bullied.

While women can be bullies, too, the vast majority of bullies are men. So, as a man, myself, I’ve felt the need to get involved to stop this kind of behavior – whether the bullying is physical, psychological or spiritual. I need to be there to stop it to be a “real man.” [Note: I wish that I knew a way to be more involved with our grandchildren so that they know how to protect themselves from cyberbullying – something my generation never had to face.]

Whenever any of us experiences or sees bullying happening, we all should know that there are safe things we can do to make it stop. Tragically, however, that’s not yet been possible for the Ukrainians who’ve been forced to face the biggest bully in today’s world: Vladimir Putin (who, I think, actually suffers from the insecurities of being a man of small stature). Not doing or saying anything in the face of any bully like that, though, will only make it worse for everyone – even the bully, himself, who will then think that it’s okay to keep treating other people that way.

So, we should all get more involved to make the cycles of bullying stop. Start at home within your own family, then move out to your community, your place of work, even within your own Church (capable of a kind of bullying of a different sort) – and don’t stop if your only influence left is the power of your vote to keep someone like Donald J. Trump out of office, finally rendered powerless, and turned back into the shadows from where he came.

7. ...“resist, to keep living in a world of crushing opposition.” But no one except Antiochus lives. I don’t understand. Comments? (p.125)

Our authors rightly point out that “No one should be a man if the ideal man is a vicious tyrant like Antiochus” – which simply means don’t be someone like him. What’s more, the reimagination of gender could actually become a way to “resist” even while “living in a world of crushing oppression.” In other words, it could make those who continue to misuse their power in abusive ways to finally lose that power over others. Then no one – regardless of gender or station in life – will ever again remain powerless.

8. If the question of whether the early movements of the Way were positive or negative toward women is the wrong question, what would you ask instead? (p.128)

How about this: “In what ways did the misuse of power by the early ‘church fathers’ affect the communal movement that became Christianity?”

Chapter 9: Belonging to Israel (pp. 130-146)

9. If you were to make an identity statement as Paul did on pg.135, what would you include?

That is a very tall order; but “off the top of my head “ my list would include:

• Cherish the life you’ve been given. With me, it’s all that it’s meant, first, to be a spirit-filled child, then a son, a brother, a friend and spiritual companion, a husband, a father, a teacher, a counselor, a pastor, and finally a grandfather.

• Nurture, in yourself as well as in others, ways to be a humane human being. Don’t be a bully.

• Find your own way to live out the truth of Micah 6: 8 – Do justice. Act with lovingkindness. And (with all sincere humility) share your own understanding of the God you know and love while inviting others to do the same.

• Accept diversity and find as many ways as you can to continue to be in an ongoing dialogue with it – because diversity is the nature of reality itself.

• Be the kind of person who will be remembered with fondness – if not love – when your gone.

10. What do you think is the difference between belonging to the God of Israel and belonging to the Methodist (or Presbyterian) church? (p.139)

The “God of Israel” is a bit more universally tyrannical than the Church has become – but both are in need of a radical top-to-bottom reformation. It’s the only way that I still continue to call myself a Christian (NOTE: my answer to Brian McLaren’s new book "Do I Stay Christian?").

11. Can you give a better one sentence or phrase description of this chapter than their final “A Messy Blend”? (p.145)

I don’t know about “better,” but how about this: “Following Jesus also meant identifying with Israel and Judaism.” ... or one of these phrases: “Jesus the Jew” or “Jesus, Israel and Judaism”

Week 3 Questions

1 – What are your thoughts on so many of the Roman emperor’s families killing each other? 67

2 – Imagine being a Roman soldier whose job it is to crucify Judeans. What does this feel like to you? 71

3 – Can you think of a modern analogy to “My God defeated your God, so we are better….”? 76

4 – Why do you think Roman policy of war against a people (but not their God[s]) changed to war against both people and their God[s]? 78

5 – What would you die for? What would you have died for in the past but no longer OR (the reverse), what would die for now but not earlier? Comments? 84

6 – How do the noble death stories in Maccabees relate to you? 87

7 – What has happened to the noble death tradition today? I don’t hear about it. 90

8 – What kind of connection (if any?) do you see between Jesus’ last supper and our book study final potluck? 92

9 – How do you feel about replacing the ! With a ? in Mark 15:39? 95

10 – Is there a better alternative to dying for truth? 96

Responses to Week 3 Questions

Chapter 5: Violence in Stone (pp. 66-80)

1. What are your thoughts on so many of the Roman emperor’s families killing each other? (p. 67)

I’m reminded of that two-pronged quote that goes something like this: “Power corrupts; but absolute power corrupts absolutely.” At the center of that dynamic are those who seek to either take away the power they see others have and they want – or the reverse – those who seek to hold onto the power they have by eliminating others who might want to take it away from them. It happens in all kinds of relationships. It just doesn’t always lead to homicide.

But look at all of the totalitarian governments across our world today that continue to function much this same way – from Vladimir Putin’s Russia to Bashar Hafez al-Assad’s Syria. The families they decimate are their own people.

2. Imagine being a Roman soldier whose job it is to crucify Judeans. What does this feel like to you? (p. 71)

Wherever capital punishment has existed, there have been executioners. While the means of execution has changed over the centuries (some, paradoxically enough, attempting to make it more “humane”), it is still maintained and controlled by the governments of those countries in which it exists – and, tragically, we’re one of them. If the executioner has convinced himself that the punishment is justified, it may just seem like another day at work.

To me it just seems like vengeance. Such executions make me feel sick. But then so does the way that the execution of Jesus has been taught by the institutional Church: as a celebration that it came to call the doctrine of substitutionary atonement. Both are an abomination – and the latter makes a horror out of God.

3. Can you think of a modern analogy to “My God defeated your God, so we are better….”? (p. 76)

I’ve an idea that members of the Taliban’s Islamic hierarchy now ruling Afghanistan feel that their recent defeat and expulsion of the armed forces of the West (U.S.A., U.K. et al.) is proof of just such a theological position.

4. Why do you think Roman policy of war against a people (but not their God[s]) changed to war against both people and their God[s]? (p. 78)

When those defeated by Rome refused to pay homage to the holy Roman empire and accept its claim of divinity for their emperors, Rome set about trying to prove to them that they were wrong.

Chapter 6: The Death of Heroes (pp. 81-96)

5. What would you die for? What would you have died for in the past but no longer OR (the reverse), what would die for now but not earlier? Comments? (p. 84)

If my death would, in any way, save innocent lives or the lives of those I love, I would accept it.

When I first became an officer in the United States Marine Corps, I thought that I might have been willing to die to protect freedom and democracy. But our war against the Vietnamese came to convince me that it had been an unjust war from the very beginning and not worth anyone’s death. Since then, I’ve felt much the same way about every war we’ve gotten ourselves into.

6. How do the noble death stories in Maccabees relate to you? (p. 87)

The only “relationship” I can see for myself is a very thin one: I might choose medically assisted euthanasia (i.e., not suicide – euthanasia, after all, literally means “a good death”) if my health and well-being had diminished to the point where I felt life was no longer worth living. By virtue of such a “voluntary” death, could it ever then be considered “noble?” I don’t think so. It would be expeditious, at best, but not in any way that I understand nobility – i.e., that it is admirable or exemplifies some form of exalted moral character.

If, by my dying, I saved the life of another person, it might be considered noble – but not if it were just simply my own death. In the final analysis, for any death to be considered a “noble” one, I think that there at least would have to be a very clear and sufficient justification for it.

7. What has happened to the noble death tradition today? I don’t hear about it. (p. 90)

As our authors point out, here, it has to be “heroic” in some way: “The hero’s noble death of resistance to the tyrant must be remembered to have its effect.” In our tradition today, I’d say that the only death that comes close to being considered “noble” in that way are those who died in defense of their comrades during a time of war and were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor – even if resistance to some kind of “tyrant” isn’t as obvious as it once seemed to be.

As a website [ https://valor.defense.gov/description-of-awards/ ] explains, the Medal of Honor is conferred upon members of the Armed Forces of the United States – but to only those who...

“...distinguish themselves through conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity

at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty:

• While engaged in action against an enemy of the United States;

• While engaged in military operations involving conflict with an

opposing foreign force; or

• While serving with friendly foreign forces engaged in an armed

conflict against an opposing armed force in which the United

States is not a belligerent party.”

If there is a “noble death tradition today” – at least in our militaristic culture – this might be it.

8. What kind of connection (if any?) do you see between Jesus’ last supper and our book study final potluck? (p. 92)

Both are gatherings in which we have come to share our love for each other in a communal meal – with the life and teachings of Jesus at the heart of our conversation. In that, we are his disciples, then, every bit as much as were those first ones (And I suspect that not only were there more than just 12, many of them were women.). So, we’re part of an ancient tradition that existed before there was ever anything called Christianity.

We are twice blessed.

9. How do you feel about replacing the ! With a ? in Mark 15:39? (p. 95)

Ambivalent. Our authors seem to think so at this point: “It could just as easily be read as sarcasm, which would be the more likely interpretation.” In the final analysis, we have no way of really knowing – and saying that we do is sheer speculation.

I like to think that Jesus died a “good” death, though – if not a noble one. That might have given rise to feelings of awe within those most intimate witnesses of his dying – whether Jesus actually said anything at all or not during those last few hours of his life.

10. Is there a better alternative to dying for truth? (p. 96)

Yes: being a witness of its value by simply, but fully, living it.

Week 2 Questions

1 – What do you think Mark 8:34 means in today’s English? Is it significant that the original Jesus Seminar voted this black? 33

2 – Do you find “Romans crucified hundreds of thousands” consistent with a single iron nail embedded in a heel? Comments? 35

3 – Find out the ratio of non-slaves (free) to enslaved people in the Roman Empire over time. 38

4 – How would “the lure of work in different parts…” be any different 2000 years ago than it is now? How many of us expected to work in our home town? 40

5 – Perhaps the original resurrection claim for Jesus was ONLY a claim of victory over Roman violence. Comments? 43

6 – Why do you think Mark has no resurrection story while that is the major theme in the rest of the gospels? 49

7 – What do you see as the biggest difference between the Roman Empire and our current first world empire? 54

8 – What do you think an engraved art piece representing the Empire of God would look like? Draw an example. 59

9 – How much do you think the idea of equality entered into early diverse Jesus groups? 62

10 – Do you think modern fundamentalism would be different if pistis had originally been translated as trust or confidence rather than belief? 64

11 – The “church” of the first 200 years grew and succeeded, partly as a reaction against the Roman Empire. How can that success be recreated now? 65

My Responses to Week 2 Questions

PART I – LIVING WITH THE EMPIRE

Chapter 3: Engine of Empire: Violence (pp. 33-51)

1. What do you think Mark 8:34 means in today’s English? Is it significant that the original Jesus Seminar voted this black? (p.33)

How about this:

“Jesus called the crowd together, along with his disciples, and said to

them all, if any of you want to follow me, you’ve got to set aside selfish

interests, endure whatever may come, and live as I have chosen to live.”

However, I would say, yes, it is significant that the Jesus Seminar voted this black (i.e., that Jesus probably didn’t say it – or that it came from a different tradition). To begin with, I think they concluded that Jesus wasn’t about creating such a following as much as he was trying to reform Judaism and the society of which he was a part. At most, he’d be calling people (in the image of Micah 6: 8) to do justice and act with kindness. What’s more, there was no shadow of a crucifixion at this point in his life, so the symbol of “taking up a cross” is completely out of context so, most likely, an insertion from a later era – probably sometime in the 2nd century CE.

2. Do you find “Romans crucified hundreds of thousands” consistent with a single iron nail embedded in a heel? Comments? (p. 35)

Yes, because most crucifixions of that era (and reputable historical accounts confirm at least that amount) didn’t bother with nails; they simply tied the people to their crosses. In that way, it took them even longer to die – and that was the whole point – a way that Rome further intimidated its opponents.

3. Find out the ratio of non-slaves (free) to enslaved people in the Roman Empire over time. (p.38)

Well, there’s this from the Wikipedia website*:

“Estimates for the prevalence of slavery in the Roman Empire vary.

Estimates of the percentage of the population of Italy who were slaves

range upwards of two to three million slaves in Italy by the end of the

1st century BC, about 35% to 40% of Italy's population. For the empire

as a whole during the period 260–425 AD, according to a study by

Kyle Harper, the slave population has been estimated at just under

five million, representing 10–15% of the total population of 50–60

million inhabitants. An estimated 49% of all slaves were owned by

the elite, who made up less than 1.5% of the empire's population.

About half of all slaves worked in the countryside where they were

a small percentage of the population except on some large agricultural,

especially imperial, estates; the remainder of the other half were a

significant percentage – 25% or more – in towns and cities as

domestics and workers in commercial enterprises and manufacturers.”

[*See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_in_ancient_Rome]

4. How would “the lure of work in different parts…” be any different 2000 years ago than it is now? How many of us expected to work in our home town? (p. 40)