This Book Study runs from July 17 through September 4.

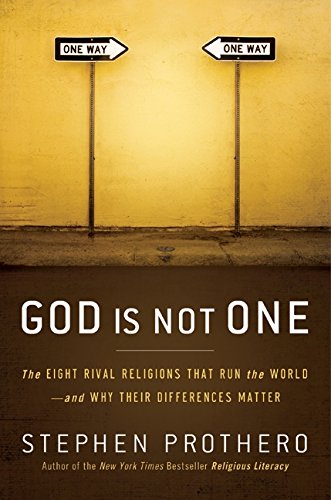

In eight chapters, Stephen Prothero sets out to evaluate eight of the world's religions:

• Islam: The Way of Submission

• Christianity: The Way of Salvation

• Confucianism: The Way of Propriety

• Hinduism: The Way of Devotion

• Buddhism: The Way of Awakening

• Yoruba Religion: The Way of Connection

• Judaism: The Way of Exile and Return

• Daoism: The Way of Flourishing

The author also offers a brief coda on Atheism: The Way of Reason.

Here are some of the high points in Prothero's express train ride through the religions. His valid insights into these different "ways" takes away some of the sting of his view of religions as rivals. Whereas the nineteenth and twentieth centuries may have belonged to Christianity, the twenty-first is in the hands of Islam with its mix of fundamentalists, moderates, and Sufi mystics. For Muslims the problem is pride, and the solution is submission.

Conservatives dominate Christianity with evangelicals and Pentecostal influences still exerting their power and presence. For these believers and others the problem is sin, and the solution is salvation.

Confucianism advocates overcoming challenges through character. This is done by cultivating ren (human-heartedness) and li (ritual, etiquette, propriety). Prothero confesses that Confucius is his "professional hero" thanks to his advocacy of learning as a pleasure and a means of becoming a better human being.

Hinduism is the umbrella term for a religious tradition that gave the world karma, reincarnation, and yoga. It puts a lot of emphasis upon devotional activities.

Buddhism is more about experience than it is about doctrine and it has much to say about suffering, speech, impermanence, and emptiness. In Buddhism, the problem is suffering and the solution is awakening.

In both Africa and in the America, Yoruba religion seeks to connect earth and heaven, human beings and orishas, and individuals with each other.

Judaism stands apart for being both a religion and a people. In this way, the problem is exile, and the solution is to return to God.

Prothero ends with an overview of Daoism with its emphasis upon nurturing life and flourishing as a human being.

Each religion, Prothero argues, has made a distinctive contribution to answering eternal questions and providing guidance for how to live one's life. Religious pluralism is alive and well in the world. Instead of trying to prove they are are One, he wants us to respect the diversity of religious faith and expression.

Book Review by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Week 8 Questions

Chapter 9 Atheism

1 – Can you only deny the gods you know? 318

2 – Which of the new (Angry) atheists have you read? How about older atheists? 319

3 – Comments on the Dawkins quote on pg 321?

4 - “Why isn’t the world exactly like us?” 323

5 – Do you think atheism is a religion? Why? 325

6 – Remember that for most of history / pre-history, there was no such thing as religion, only culture. 326

7 – What kind of atheism do you hear from me? 328

Conclusion

8 – How satisfied are you with your religion? How satisfied are you with your religious community? 333

9 – How well do we do as a group at understanding our individual differences? Does this help you outside our group? 335

10 – Does your worldview control what is available for your religion, or does your religion control what is available for your worldview? Or, if neither, how does it work for you? 337

My Responses to Week 8 Questions

Chapter 9 – Atheism

1 – Can you only deny the gods you know? 318

A somewhat flippant response might be, “If you don’t know what you’re talking about, then just shut up.” I do understand, however, the conundrum behind the question. As for me, I deny all gods that simply do not make any sense to me. And since most gods are human inventions anyway, most of this is pure speculation.

2 – Which of the new (Angry) atheists have you read? How about older atheists? 319

I haven’t read enough of any of them in depth to be worth a comment. I don’t read what they have to say because most seem to completely discount religion and spirituality to begin with. I find that almost as disturbing as the extreme right wing fundamentalists who, in much the same way, are completely closed to any true dialogue. Prothero, himself, points out the problem for me when he says that most (if not all) atheists consider religion itself to be the problem, that it is “murderous – irrational, superstitious, and hazardous to our health” [p. 318].

3 – Comments on the Dawkins quote on pg. 321?

The most problematic sentence there, for me, is his sweeping conclusion that “Revealed faith is …dangerous nonsense…because it gives people unshakeable confidence in their own righteousness.” I have faith in deeply felt – profoundly spiritual – moments that have been revealed to me throughout my entire life. But they haven’t given me “unshakeable confidence” in my “own righteousness.” Those experiences are my own. I don’t impose them on anyone. But I have found it compelling, interesting and ultimately worthwhile to be able to share such experiences with others who’ve had much the same kinds of experiences and want to explore the ways that we might respond to them – both individually and communally. For me, that’s what “church” is all about.

4 - “Why isn’t the world exactly like us?” 323

Because it just isn’t – and never will be. So, get over it.

5 – Do you think atheism is a religion? Why? 325

As I’ve come to understand and interpret religion, it’s the kind of deep devotion (personal and/or communal) to an ideal that then becomes a conscientious concern for and commitment to whatever matters most to us in life. Religion not only aligns a person with his/her values, but can become a total way that person interprets and lives his/her life. When it’s identified with a community, it can be the very thing that “binds” people together (cf. the Latin religare which means “to bind” – as in a church, a synagogue, or mosque).

If atheism does all those things, for anybody, I suppose that it could be defined as a religion. I can’t imagine, however, any atheist claiming to be “religious” in that sense. The very word is anathema to an atheist. Religion for most atheists (as Prothero points out) is the enemy, so they probably would identify with being “anti-religious” [p. 323].

6 – Remember that for most of history / pre-history, there was no such thing as religion, only culture. 326

That’s not the way I read history. Religion has always been an integral part of people’s lives and therefore part of the cultures that they’ve created. In that sense I agree with Prothero’s interpretation here of Tillich that religion “stands at the center of their lives, defining who they are, how they think, and with whom they associate.”

7 – What kind of atheism do you hear from me? 328

If you’re talking about yourself here, Peter, I certainly haven’t experienced you as an “angry man” spewing out disbelief. If you didn’t care so much about religion you wouldn’t be spending so much of your time hearing, reading and talking about it (Okay, maybe Evelyn has something to do with it!). You definitely are unorthodox in your approach toward religion, but then so am I!

Most of us, I suspect, are actually agnostics – i.e., we cannot, in all honesty and unequivocally, say that there is a God or that there is no God. We either can’t agree on the term or concept, or we simply do not and cannot know for certain. The more that I ponder the reality of God, the more Mysterious and incomprehensible (i.e., impossible to fully understand) that concept has become for me.

That does not mean, however, that God is fundamentally inconceivable and therefore unreal or nonexistent. As with most journeys, for me the search has become more important than the destination.

Conclusion

8 – How satisfied are you with your religion? How satisfied are you with your religious community? 333

As I have defined “religion” [see the first part of my response in question #5 above], I am fairly satisfied with mine. If, however, I had to define my “religious community” as limited only to the denomination called The United Methodist Church, I am profoundly dissatisfied with it. Theologically, I now probably have more in common with Unitarian Universalists. But my closest companions on this journey have been, and remain to be, deeply committed Christians. That is my heritage. That is the community with which I most clearly identify. But I will keep the dialogue going with and among all who care enough to want to do so [NOTE: I said “dialogue” here, not “debate.”].

9 – How well do we do as a group at understanding our individual differences? Does this help you outside our group? 335

I’m not sure how “well” we do this. For some of us who’ve been used to this free-wheeling dialogue – indeed, thrive on it – we feel completely comfortable speaking up and feel as if we’ve been heard. For others, who’ve not felt comfortable speaking up in other settings, and/or don’t think that they “know enough” to speak their mind, we may not be doing as well as we could to make them feel “safe” and comfortable.

So I do agree with Prothero here who says “we must start with a clear-eyed under-standing of the fundamental differences in both belief and practice.” And he does a good job describing what, for me, is the meaning of true dialogue: “What is required in any relationship is knowing who the other person really is.” Denying our differences only leads to disaster. “What works is understanding the differences and then coming to accept, and perhaps even to revel in, them.”

Prothero goes on to say (and I agree with him), “genuine dialogue across religious boundaries must recognize the existence of these boundaries and the fundamental difference between the lands they bisect” [p. 336].

I think our conversations – our dialogue – over these Sunday evening gatherings do help me outside the group, because it helps me coalesce my thoughts, opinions and beliefs into a more cogent theology – if not for others then certainly for me.

10 – Does your worldview control what is available for your religion, or does your religion control what is available for your worldview? Or, if neither, how does it work for you? 337

I agree with Prothero here when he says, “people act every day on the basis of religious beliefs and behaviors that outsiders see as foolish or dangerous or worse.” I know that I do. But, as Prothero says at the close, “the claim that all religions are one is no more effective than the claim that all religions are poison” [p. 340]. I’ve been called everything from a hopeless idealist to a sinner who will be damned to hell. But I try very hard to do what I say and to say why I do what I do.

So I continue to try to bring together both my worldview and my religion. To me they should never be separate – one should not control the other but each should inform the other. For most of my life I’ve avoided being pigeon-holed into such “either/or” positions. I’ve always been more of a “both/and” kind of person – i.e., both my worldview and my religion are important to me, and I can tell you why.

How about you?

Week 7 Questions

Chapter 6 – Yoruba

1 – How much does the problem of disconnection and its associated solution of reconnection resonate with you? 206

2 – Would you prefer the Christian god of perfection or the Yoruba gods of the people? 209

3 – Can you think of another religious interaction with technology like Eshu and the computer/internet? 213

4 – Which of the sections did you find most interesting, and why? 216+

Chapter 8 – Daoism

5 – Why does half the world see life as all there is while the other half see the after life as the final destination? Is one half or the other gaining? 279

6 – Is wandering important in your life? Do you wander now more or less than in the past? Why? 284

7 – How do you get to be a sage without learning how to live in society? 287

X – DO NOT experiment with cinnabar!

8 - “when everyone acts authentically and without artifice the natural result is social order.” Comments? 293

9 – Does maturity look the same (or at least very similar) in all cultures and religions? 306

10 – Compare Lord Lao with Jesus Christ. 309

My Responses to Week 7 Questions

Chapter 6 – Yoruba

1 – How much does the problem of disconnection and its associated solution of reconnection resonate with you? 206

It very much resonates with me. Early on in his exposition of the Yoruba religion, Prothero pointed out that even his students recognized that “Much of our sadness and suffering…comes from trying to live a life other than our own. So each of us should seek to discover our purpose and pursue it with passion and resolve” [pp. 203-204]. That speaks of our disconnection and need for reconnection. Curiously enough, for a very long time I’ve told myself and others just that: “Find your passion and pursue it!”

So, “for the Yoruba, as for the ancient Greeks, wisdom is recalling what we already know within” us [p. 205]. If we can come to know how truly disconnected we are – from ourselves and our environment – the solution might just present itself to us. And that solution begins with reconnecting ourselves to the person we were created to be, as well as “to one another, and to the sacred power” which animates us all.

I don’t believe, however, that this is “accomplished through the techniques of divination, sacrifice, and spirit/body possession” unless that means, simply, being in touch with the spirit that resides within us all – accepting the presence, fundamentally, of who we are.

2 – Would you prefer the Christian god of perfection or the Yoruba gods of the people? 209

First of all, I would question the assumptive dichotomy that “the Christian god” is a “god of perfection” whereas “the Yoruba gods” are “gods of the people.”

I do like the fact, however, that “the Yoruba put huge stock in the capacities of human beings” and that we are “animated by the same sacred power that animates the orishas” [p. 205]. They call it ashe and, as Prothero understands it, it’s “the awesome power to make things happen” [p. 209]. If that’s what we have in common with “the gods,” then I affirm it.

Just like the god of the Bible, however, I could never embrace the Yoruba gods which are simply anthropomorphized versions of the best and worst in ourselves. For the Yoruba the orishas are neither all good or all evil. “They can be generous and petty, merciful and vengeful. They can harm as well as heal” [pp. 208-209]. That sounds bizarrely human-like to me. That is definitely not how I understand God.

In the end, if what we share with God/the gods, however, is this “equally awesome power to make things change” – to make things happen – then I agree with that and affirm it. But I also believe that’s a feature of “the Christian god” every bit as much as it seems to be a feature of “the Yoruba gods of the people.”

I like something Prothero says along this line just a bit later: “The net effect of this net of correspondences is to make everything, everyone and everywhere potentially sacred. Every moment presents a possibility to reconnect with the orishas and, through them, with your destiny and the harmony that pursuing it brings” [p. 210]. That sounds very much like the Hebrew concept of shalom to me. In the end what we’re really pursuing is wholeness, health, harmony, self-actualization (being the best person that we can be)…and being at peace with it. I embrace that aspiration – wholeheartedly.

3 – Can you think of another religious interaction with technology like Eshu and the computer/internet? 213

To begin with, as I understand Prothero’s explanation of Eshu, that orisha, “as the holder of ashe,…has the power to take almost any situation in whatever direction he pleases” [p. 212]. That sounds dangerously capricious to me – and very much like a human being who’s been given far too much power. What’s more Eshu is portrayed as “the trickster” – “He inserts uncertainty and unpredictability into a world otherwise governed by fate, and he then sits back and laughs at the chaos that follows” [p. 213]. I cannot give any credence at all to such a god. And it certainly doesn’t explain computer malfunctions, viruses or other malware.

This may be, however, how some people misunderstand the Hindu concept of karma – i.e., that one’s decisions and actions (bad or good) will come back to haunt you. And yet even the Bible has parallels:

• “Whoever digs a pit will fall into it, and a stone will come back on him who starts it rolling.” – Proverbs 26: 27

• “His mischief returns upon his own head, and on his own skull his violence descends.” – Psalm 7: 16

• “As I have seen, those who plow iniquity and sow trouble reap the same.” – Job 4: 8

• “Do not be deceived: God is not mocked, for whatever one sows, that we he also reap.” – Galatians 6: 7

• “So whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them, for this is the Law and the Prophets.” – Matthew 7: 12

In the end, I really can’t think of any “religious interaction with technology.”

4 – Which of the sections did you find most interesting, and why? 216+

If I’m forced to choose from p. 216 forward, I’d pick up on the thread begun in the section entitled “Elasticity” [p. 230f.] – specifically where Prothero says that “Yoruba religion sees the human problem as disconnection. To be human is to be connected…. We are even disconnected from our destinies, alienated from our truest selves. Yoruba practices seek to reconnect us across all these divides” [p. 232]. This is how I’ve come to understand, once again, that Hebrew concept of shalom which is so central to my theology. In this case it might also be compared to the peak of Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” – which he labeled “self-actualization” [take a moment to view the explanation at http://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html Our task, finally, is simply to become the best kind of human being that we can – to strive to become who we were always meant to be.

Prothero comes full circle on this interpretation, I think, in his closing section of the Yoruba religion entitled “Flourishing” [p. 240f.]. Religion should never be focused upon life-after-death concerns. Instead, “religion’s primary purpose is to make sense not of death but of birth, not of destruction but of creation… where religions really compete is on the question of how to flourish” [pp. 240-241]. Our very reason for being is “to repair our lives and our world by reconnecting earth and heaven…each of us with our own particular destinies and natural environments” [p. 241]. I hear an echo of tikkun olam (the Jewish concept of repairing our world) in this. I see it again, as well, in Daoism where “led only by intuition and desire and the innate curiosity of the child, is to discover who you really are – your natural spontaneity, vitality, and freedom” [p. 280]. Not surprisingly, I very much like this idea. Our task as human beings is to keep at it over and over and over again. One day, we may finally get it right!

Chapter 8 – Daoism

5 – Why does half the world see life as all there is while the other half see[s] the after life as the final destination? Is one half or the other gaining? 279

I’m not sure that dichotomy is all that clearly defined (i.e., 50/50). And I don’t pretend to know the reasons for one over the other. However, it could be that those cultures whose people are constantly having to struggle just to survive, or for whom life is marked by endless suffering in the face of outside forces, these cultures might come up with life-after-death scenarios as their way of coping – their only hope of rescue.

On the other hand, if you are in a culture of people that finds much to celebrate about life as it is, you’ll probably embrace and focus more on the present and your role in it. This world is the most important one, not some mythical one that you will find and expect to enter only after your death.

6 – Is wandering important in your life? Do you wander now more or less than in the past? Why? 284

I have a kayaker’s t-shirt that has a marvelous picture of the outdoors – centered, of course, with a kayaker on a body of water – and the caption simply says, “Not all who wander are lost.” I love that expression! It’s actually a close quote from a poem written by J.R.R. Tolkien for The Lord of the Rings and describes the character Aragorn:

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken,

The crownless again shall be king.

That first line, of course, is a variant and rearrangement of the proverb “All that glitters is not gold” known primarily from Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice, but here it takes on a completely different meaning: Aragorn is a far more important person then he looks. And the second line emphasizes the importance of the Rangers, suspiciously viewed as vagabonds (“wanderers”) by those that the Rangers actually protect from evil.

In so many ways I’ve always thought of myself as a “wanderer.” But I have never felt as if I were lost. It’s much like another saying that I embrace which says, “It’s all about the journey, not the destination.” I’ve become quite content to continue to wander every bit as much as I did as a child. More than that, it’s an essential part of who I believe I am.

Thanks, very much Peter, for this question!

7 – How do you get to be a sage without learning how to live in society? 287

X – DO NOT experiment with cinnabar!

As I understand Prothero’s explanation of Daoism, “Whereas Christians and Muslims tend to view this world as a dress rehearsal for the world to come, ‘This is it!’ is the Daoist mantra” [p. 279]. So Daoism is about discovering “who you really are – your natural spontaneity, vitality, and freedom” [p. 280]. What’s more, “most Daoists agree that the highest value is life, so the highest practice is the art of nurturing life” [p. 285]. It seems to me, then, that you can’t be a true Daoist, let alone become a sage, “without learning how to live in society.”

Supposedly Daoism believes that “social harmony…is possible only when everyone does what they naturally do” [p. 286]. So “the ‘genuine person’ (zhenren) – functions as the exemplar in the Daoist tradition. …the sage acts authentically and spontaneously, without expectation or goal. … And the sage embodies” what it means to be nurtured “back to life, … combining in his own body the vitality of the child and the potency of the mother” [p. 287].

Wouldn’t all of this actually be in harmony with “learning how to live in society?” I think so.

And, no, I would not want to explore the possibilities for immortality by experimenting with alchemy – whether it be cinnabar, LSD, or any other “elixir of immortality” that you might grind out “with mortar and pestle”… [pp. 305-306]!

8 - “when everyone acts authentically and without artifice the natural result is social order.” Comments? 293

As long as this excludes the clinically insane, the Trump-level-wealthy narcissist, the bigot, the wounded bully, the…etcetera – do you get my drift? – this might make sense. Unfortunately, far too many of us, however, seem to be ruled by our flaws and not our “higher powers.” The key, as I understand Prothero’s explanation here, is that “untamed nature” and “the way of authentic human life” must find a “harmonious union.” Unfortunately, all too often what we see and experience instead is disharmony, dissension, animosity and conflict.

Which would bring me back, yet again, to what I find attractive about the essential power intrinsic in the Hebrew concept of shalom.

9 – Does maturity look the same (or at least very similar) in all cultures and religions? 306

In short, no. I would agree, however, that most cultures and authentic religions probably would affirm “the proximate goal of human flourishing: good health, long life, and vitality” [p. 306]. If that’s one feature of “maturity,” then I affirm it. But I also understand maturation as the kind of natural growth development that would allow anyone – or any culture for that matter – to become all that he/she/it could possible be in every healthy sense of such a fulfillment of those possibilities. In that sense, many cultures and religions have that in common.

10 – Compare Lord Lao with Jesus Christ. 309

If one assumes that “Lord Lao” and Jesus as “the Christ” both embodied Quanzhen (“Complete Perfection” or “Perfect Realization”), then I don’t see it. No human being has ever been completely perfect or realized anything close to perfection. What’s more, this Wang character seems to be more than a little bit off to me (...”digging a grave for himself and living in it for three years”). Is this the actual history of Lao-tzu (or Laozi)? I doubt it.

If what is meant by the essence of Daoism, however, that it “is nothing more magical than a life well lived” [pp. 313-314], then I would claim Jesus of Nazareth to have been an admirable example. I don’t know enough about “Lord Lao” to be able to claim the same for him.

Week 6 Questions

Chapter 7, Judaism

1 – Why do you think Jews have been so influential in American culture? 246

2 – Why do you think “a large minority of Jews do not believe in god.”? 248 What about the Shema? 251

3 – If the problem is exile, should the solution be return, or should it be something else? 253

4 – What does it mean to say that Judaic monotheism is ethical? 258

5 – What does it fee like to “go[..] forth from Egypt.”? 265

6 – (Extra Credit) Bring a Haggadah to read.

7 – which modern branch of Judaism would you fit into best? Why? 270

8 – How do you feel (or think) about Zionism? 272

9 – Compare Kabbalism with the Gospel of Mary. 275

10 – What characteristics of Judaism do you like best?

My Responses to Week 6 Questions on Judaism

1 – Why do you think Jews have been so influential in American culture? 246

As Prothero points out earlier, “The Jewish narrative is a story of slavery and freedom… But above all else it is a story of a people banished and then called home – a story of exile and return” [p. 243]. So I think that America’s heritage (problematic though it may be) of welcoming refugees and immigrants, of offering a home for everyone looking for a new beginning, has uniquely appealed to Jews looking for exactly that. What’s more, again as Prothero points out, because a central tenet of their faith is “to repair the world (tikkum olam),” for most Jews “redemption is thisworldly, accomplished not in heaven but here on earth. And it comes by doing rather than believing” [p. 245]. Both of these aspects have then become tremendous motivations for Jews to “do well” in this life – wherever they may be.

2 – Why do you think “a large minority of Jews do not believe in God.”? 248 What about the Shema? 251

I think that so many Jews “do not believe in God” because whether one “believes” or not is not central to that religion. It certainly is not in the way that so many who claim to be Christians say that “belief” must be central to Christianity. So I like what Prothero says in the very next paragraph: “That there are as many Jewish opinions as there are Jews…” Judaism has long been a religion which considers disagreements helpful, indeed, “that disagreements are a path to learning” and arguing should be viewed as simply “trying to get at the truth” [p. 248]. As Prothero goes on to say, “What is required in Judaism is not to agree, but to engage” [p. 249]. Because of this innately Jewish mindset, it makes good sense to me, then, that a Jew might say, “I don’t believe in God.” But the way in which I hear that statement is that the person actually may be saying, “I don’t believe in your God. Give me one good reason why I should?” It’s an invitation to an argument. And that, I think, is healthy.

In that same vein, Prothero points out that “Jews are trained not just to abide ambiguity but to glory in it. If, as Oscar Wilde wrote, ‘The well-bred contradict other people’ while ‘the wise contradict themselves,’ the Jewish scriptures are wisdom personified” [p. 250]. It certainly does make for stimulating conversation!

And as far as the Shema is concerned (as Prothero rightly points out), “Judaism has no real creed” even though the Shema “does function as a creed of sorts…” [p. 251]. However even the Shema itself “points beyond doctrine to practice, underscoring Judaism’s affinity for doing over believing, orthopraxy over orthodoxy” [p. 252]. Even the “quasi-creed” of Maimonides “was controversial and not universally accepted” [p. 252, cf. end-note #17 on p. 366]. Which leads Prothero to conclude (and rightly so, I think) that “Judaism has always been more about practice than belief” [p. 252].

I might add that this might be the real genius of Judaism and the central reason for its remarkable staying power. As Prothero puts it, “The purpose of this tradition was not to solve the human problem but to keep a people together. … Not to believe something but to do something – to repair the world (tikkun olam)” [p. 252]. It’s genius. Would that it were done.

3 – If the problem is exile, should the solution be return, or should it be something else? 253

In much the same way that most people (even Muslims) misunderstand the concept of jihad (i.e., that it ought to be about a personal struggle for goodness before it is anything else), the exile/return motif in Judaism is more than just “getting back home.” It’s about striving “to make things ready and to make things right” – again, “to ‘repair the world’” – and, as Prothero again reminds us, that’s what will “put an end to exile” [p. 254]. Neither the Jews nor we are anywhere near that yet.

4 – What does it mean to say that Judaic monotheism is ethical? 258

I think it might mean that however the Jews might see their God as having “failed” them, they still maintain that their faith requires that any relationship between one human being and another ought to be ethical. Yes, it is odd that while Jews might view God as a failure, so many continue to “trust in God.” Maybe they conclude that it’s only because God asks so much more of them than they already have given. It just doesn’t make sense to a Jew that an “all-powerful” God isn’t also “all-good.” What would be the point of that?

5 – What does it feel like to “go[..] forth from Egypt.”? 265

First of all, I think Prothero’s right when he says there, …”if this story is not also our story, then it is not worth retelling.” If you’ve never felt imprisoned, exiled, or set apart in any way as inferior, then you absolutely cannot know what it might feel like to be one who’s “gone forth from Egypt.”

On the other hand, as this daughter who’s been able to interpret “the Exodus story through the prism of the civil rights movement,” any experience of exile can be reinterpreted by this story and become a deeply powerful image of personal liberation.

6 – (Extra Credit) Bring a Haggadah to read.

I wouldn’t know how to choose because I’m not Jewish, but in case you’re interested in exploring the genre, here’s a wonderful resource: www.haggadot.com. Check it out.

7 – Which modern branch of Judaism would you fit into best? Why? 270

I can’t be limited to just one, but these following features are what I find most intriguing:

• from Reconstructionist Judaism: “God” is only “an expression of the highest ethical ideals of human beings.” In that sense this form of Judaism is “not a supernatural religion but an evolving civilization” [p. 270]. I think that’s what any religion ought to be about, otherwise it keeps us captive to outdated theology and enslaved to such phrases as “But we’ve always done it this way!”

• from Humanistic Judaism: We ought to celebrate what’s best of “Jewish culture and the power of the individual without invoking God, praying to God, or reading from the revelation of God. For Humanistic Jews, Judaism is first and last about ethics – doing ‘good without God’” [p. 271]. Why do we always have to appeal to a transcendent deity for salvation when we already have within our power the capability of being the best person we can possibly be?

• from Feminist Theology: If one does feel compelled to anthropomorphize God (and I do not), let’s at least transcend gender-specific references (i.e., solely patriarchal) and consider both the compelling and endearing aspects presented by feminine points of view – after all, sophia, the Greek word for wisdom, is a feminine noun. Let’s take the best masculine and feminine points of view that, at least historically, have been restricted to only one gender.

• from the mystical tradition of the Kabbalah: Because I am one who continues to be fascinated by spirituality and the kind of longing for the More that I associate with my own spiritual journey, I agree that any “experience of what we call God is bigger and more mysterious than anything the term Judaism might convey” [p. 274]. From this point of view “God is said to be Ein Sof, which is to say endless and limitless and beyond mental grasping” [p. 275]. “Another key concept in Kabbalah is Shekhina, the feminine and immanent aspect of God,” which fits with my Christian interpretation that, in fact, “the Kingdom of God is within you” (cf. Luke 17: 21 and Leo Tolstoy’s philosophical treatise in which he uses that very phrase for the title of one of his books).

For anyone who might be interested, this is also why I have the following statement about myself on the Spiritual Directors International website (www.sdiworld.org):

“I offer Spiritual Direction from a distinctively interspiritual perspective – that just means I believe that there are many ways of experiencing the Sacred. There is so much more to the nature of the Holy than can ever be disclosed within any one religion. It's not about correct doctrine or orthodox belief, finally; it's about nourishing that relationship with the Sacred that’s already within you – one that is accessible to us all.”

8 – How do you feel (or think) about Zionism? 272

I can understand how an historically “homeless” race of people would find the “homecoming” aspects of Zionism compellingly attractive. As Prothero rightly points out, “The Holocaust proved to be the tipping point for the Zionist cause” [p. 272]. I have trouble, however, identifying that horrendous event with the phrase that followed: “the biblical Promised Land” – as if 20th century Jews had a better claim on “a Jewish homeland” than the Palestinian people who actually lived there when the state of Israel was “arbitrarily created” in 1948.

9 – Compare Kabbalism with the Gospel of Mary. 275

As we’ve read in this gnostic gospel, Mary Magdalene appears as a disciple, singled out by Jesus for special teachings. Jesus supposedly said – and only to Mary – cryptic things like “…where the mind is, there is the treasure” and “the All is being dissolved, both the earthly and the heavenly”…”What binds me has been slain, and what surrounds me has been overcome, and my desire has been ended and ignorance has died” …. Of course, Peter is made to play the patriarchal “Father-knows-best” role and finds it preposterous that Jesus would ever “speak with a woman without our [i.e., the guys’] knowledge”…. Isn’t that “just like a man?”

I suppose that what this gospel has in common with Kabbalistic thought is, as Prothero points out: “Our job is to reverse this primordial exile of the many from the One, to return the sparks inside us and inside everything around us to their original wholeness” [p. 275]. Where a Jew would say that you accomplish this by following the commandments of God that one can find in Scripture, I suspect the gnostic parallel would be that gnosis can be reached by practicing philanthropy to the point of personal poverty and diligently searching for wisdom by helping others.

But then Gnosticism has a wide variety of meanings, so who knows?

10 – What characteristics of Judaism do you like best?

If it could be summed up in one word it might be “midrash” – everything, and I mean absolutely everything, in Judaism is open to interpretation and commentary. I like that. It says to me, “Let’s talk. You tell me how you interpret it, and I’ll tell you how I see it.” That’s the foundation of any and every healthy dialogue. It’s not about hitting each over the head with some biblical text, doctrine or dogma, but reinterpreting it in light of new and present knowledge. So I agree with Prothero’s observation that “The Jewish tradition has always been a dance, or perhaps a wrestle, between the old and the new. And it is this give and take that keeps it vital.” …. “…what has kept it alive is conversation and controversy” [p. 277]. A central aspect of Judaism that I like, then, is that it’s all about the “narrative” – of telling and retelling the stories, and yet giving them new spin and understanding them in a modern context [cf. p. 243].

I also like the concept of tikkun olam – that our task is to “repair” a broken world in whatever ways that we can clearly see that it is broken and in need of remaking. In the end it’s about “doing” more than it is about “believing.” If you forget that then you’ve also forgotten the story and the reasons why it was told in the first place.

My Responses to Week 6 Questions on Judaism

1 – Why do you think Jews have been so influential in American culture? 246

As Prothero points out earlier, “The Jewish narrative is a story of slavery and freedom… But above all else it is a story of a people banished and then called home – a story of exile and return” [p. 243]. So I think that America’s heritage (problematic though it may be) of welcoming refugees and immigrants, of offering a home for everyone looking for a new beginning, has uniquely appealed to Jews looking for exactly that. What’s more, again as Prothero points out, because a central tenet of their faith is “to repair the world (tikkum olam),” for most Jews “redemption is thisworldly, accomplished not in heaven but here on earth. And it comes by doing rather than believing” [p. 245]. Both of these aspects have then become tremendous motivations for Jews to “do well” in this life – wherever they may be.

2 – Why do you think “a large minority of Jews do not believe in God.”? 248 What about the Shema? 251

I think that so many Jews “do not believe in God” because whether one “believes” or not is not central to that religion. It certainly is not in the way that so many who claim to be Christians say that “belief” must be central to Christianity. So I like what Prothero says in the very next paragraph: “That there are as many Jewish opinions as there are Jews…” Judaism has long been a religion which considers disagreements helpful, indeed, “that disagreements are a path to learning” and arguing should be viewed as simply “trying to get at the truth” [p. 248]. As Prothero goes on to say, “What is required in Judaism is not to agree, but to engage” [p. 249]. Because of this innately Jewish mindset, it makes good sense to me, then, that a Jew might say, “I don’t believe in God.” But the way in which I hear that statement is that the person actually may be saying, “I don’t believe in your God. Give me one good reason why I should?” It’s an invitation to an argument. And that, I think, is healthy.

In that same vein, Prothero points out that “Jews are trained not just to abide ambiguity but to glory in it. If, as Oscar Wilde wrote, ‘The well-bred contradict other people’ while ‘the wise contradict themselves,’ the Jewish scriptures are wisdom personified” [p. 250]. It certainly does make for stimulating conversation!

And as far as the Shema is concerned (as Prothero rightly points out), “Judaism has no real creed” even though the Shema “does function as a creed of sorts…” [p. 251]. However even the Shema itself “points beyond doctrine to practice, underscoring Judaism’s affinity for doing over believing, orthopraxy over orthodoxy” [p. 252]. Even the “quasi-creed” of Maimonides “was controversial and not universally accepted” [p. 252, cf. end-note #17 on p. 366]. Which leads Prothero to conclude (and rightly so, I think) that “Judaism has always been more about practice than belief” [p. 252].

I might add that this might be the real genius of Judaism and the central reason for its remarkable staying power. As Prothero puts it, “The purpose of this tradition was not to solve the human problem but to keep a people together. … Not to believe something but to do something – to repair the world (tikkun olam)” [p. 252]. It’s genius. Would that it were done.

3 – If the problem is exile, should the solution be return, or should it be something else? 253

In much the same way that most people (even Muslims) misunderstand the concept of jihad (i.e., that it ought to be about a personal struggle for goodness before it is anything else), the exile/return motif in Judaism is more than just “getting back home.” It’s about striving “to make things ready and to make things right” – again, “to ‘repair the world’” – and, as Prothero again reminds us, that’s what will “put an end to exile” [p. 254]. Neither the Jews nor we are anywhere near that yet.

4 – What does it mean to say that Judaic monotheism is ethical? 258

I think it might mean that however the Jews might see their God as having “failed” them, they still maintain that their faith requires that any relationship between one human being and another ought to be ethical. Yes, it is odd that while Jews might view God as a failure, so many continue to “trust in God.” Maybe they conclude that it’s only because God asks so much more of them than they already have given. It just doesn’t make sense to a Jew that an “all-powerful” God isn’t also “all-good.” What would be the point of that?

5 – What does it feel like to “go[..] forth from Egypt.”? 265

First of all, I think Prothero’s right when he says there, …”if this story is not also our story, then it is not worth retelling.” If you’ve never felt imprisoned, exiled, or set apart in any way as inferior, then you absolutely cannot know what it might feel like to be one who’s “gone forth from Egypt.”

On the other hand, as this daughter who’s been able to interpret “the Exodus story through the prism of the civil rights movement,” any experience of exile can be reinterpreted by this story and become a deeply powerful image of personal liberation.

6 – (Extra Credit) Bring a Haggadah to read.

I wouldn’t know how to choose because I’m not Jewish, but in case you’re interested in exploring the genre, here’s a wonderful resource: www.haggadot.com. Check it out.

7 – Which modern branch of Judaism would you fit into best? Why? 270

I can’t be limited to just one, but these following features are what I find most intriguing:

• from Reconstructionist Judaism: “God” is only “an expression of the highest ethical ideals of human beings.” In that sense this form of Judaism is “not a supernatural religion but an evolving civilization” [p. 270]. I think that’s what any religion ought to be about, otherwise it keeps us captive to outdated theology and enslaved to such phrases as “But we’ve always done it this way!”

• from Humanistic Judaism: We ought to celebrate what’s best of “Jewish culture and the power of the individual without invoking God, praying to God, or reading from the revelation of God. For Humanistic Jews, Judaism is first and last about ethics – doing ‘good without God’” [p. 271]. Why do we always have to appeal to a transcendent deity for salvation when we already have within our power the capability of being the best person we can possibly be?

• from Feminist Theology: If one does feel compelled to anthropomorphize God (and I do not), let’s at least transcend gender-specific references (i.e., solely patriarchal) and consider both the compelling and endearing aspects presented by feminine points of view – after all, sophia, the Greek word for wisdom, is a feminine noun. Let’s take the best masculine and feminine points of view that, at least historically, have been restricted to only one gender.

• from the mystical tradition of the Kabbalah: Because I am one who continues to be fascinated by spirituality and the kind of longing for the More that I associate with my own spiritual journey, I agree that any “experience of what we call God is bigger and more mysterious than anything the term Judaism might convey” [p. 274]. From this point of view “God is said to be Ein Sof, which is to say endless and limitless and beyond mental grasping” [p. 275]. “Another key concept in Kabbalah is Shekhina, the feminine and immanent aspect of God,” which fits with my Christian interpretation that, in fact, “the Kingdom of God is within you” (cf. Luke 17: 21 and Leo Tolstoy’s philosophical treatise in which he uses that very phrase for the title of one of his books).

For anyone who might be interested, this is also why I have the following statement about myself on the Spiritual Directors International website (www.sdiworld.org):

“I offer Spiritual Direction from a distinctively interspiritual perspective – that just means I believe that there are many ways of experiencing the Sacred. There is so much more to the nature of the Holy than can ever be disclosed within any one religion. It's not about correct doctrine or orthodox belief, finally; it's about nourishing that relationship with the Sacred that’s already within you – one that is accessible to us all.”

8 – How do you feel (or think) about Zionism? 272

I can understand how an historically “homeless” race of people would find the “homecoming” aspects of Zionism compellingly attractive. As Prothero rightly points out, “The Holocaust proved to be the tipping point for the Zionist cause” [p. 272]. I have trouble, however, identifying that horrendous event with the phrase that followed: “the biblical Promised Land” – as if 20th century Jews had a better claim on “a Jewish homeland” than the Palestinian people who actually lived there when the state of Israel was “arbitrarily created” in 1948.

9 – Compare Kabbalism with the Gospel of Mary. 275

As we’ve read in this gnostic gospel, Mary Magdalene appears as a disciple, singled out by Jesus for special teachings. Jesus supposedly said – and only to Mary – cryptic things like “…where the mind is, there is the treasure” and “the All is being dissolved, both the earthly and the heavenly”…”What binds me has been slain, and what surrounds me has been overcome, and my desire has been ended and ignorance has died” …. Of course, Peter is made to play the patriarchal “Father-knows-best” role and finds it preposterous that Jesus would ever “speak with a woman without our [i.e., the guys’] knowledge”…. Isn’t that “just like a man?”

I suppose that what this gospel has in common with Kabbalistic thought is, as Prothero points out: “Our job is to reverse this primordial exile of the many from the One, to return the sparks inside us and inside everything around us to their original wholeness” [p. 275]. Where a Jew would say that you accomplish this by following the commandments of God that one can find in Scripture, I suspect the gnostic parallel would be that gnosis can be reached by practicing philanthropy to the point of personal poverty and diligently searching for wisdom by helping others.

But then Gnosticism has a wide variety of meanings, so who knows?

10 – What characteristics of Judaism do you like best?

If it could be summed up in one word it might be “midrash” – everything, and I mean absolutely everything, in Judaism is open to interpretation and commentary. I like that. It says to me, “Let’s talk. You tell me how you interpret it, and I’ll tell you how I see it.” That’s the foundation of any and every healthy dialogue. It’s not about hitting each over the head with some biblical text, doctrine or dogma, but reinterpreting it in light of new and present knowledge. So I agree with Prothero’s observation that “The Jewish tradition has always been a dance, or perhaps a wrestle, between the old and the new. And it is this give and take that keeps it vital.” …. “…what has kept it alive is conversation and controversy” [p. 277]. A central aspect of Judaism that I like, then, is that it’s all about the “narrative” – of telling and retelling the stories, and yet giving them new spin and understanding them in a modern context [cf. p. 243].

I also like the concept of tikkun olam – that our task is to “repair” a broken world in whatever ways that we can clearly see that it is broken and in need of remaking. In the end it’s about “doing” more than it is about “believing.” If you forget that then you’ve also forgotten the story and the reasons why it was told in the first place.

Week 5 Questions

Buddhism

1 – What did you know about Buddhism before reading this chapter and what do you “know” differently now?

2 – What have you learned about Buddhism from popular media? 176

3 – What Buddhist meditations have you tried? 178

4 – The “self is a figment of the imagination.” Comments? 179

5 – Does the Eightfold Path imply that we should stifle our emotions (entirely)? 183

6 – What do you do to eliminate suffering? Does it work? 187

7 – How do you feel or think about koans? 192

8 - “Trust only what you yourself have seen to be true in your own experience.” Comments? 199

My Responses to Week 5 Questions

1 – What did you know about Buddhism before reading this chapter and what do you “know” differently now?

I did know about Siddhartha Gautama being a royal prince who “walked away from it all” to become “a wandering holy man” (p. 171). I did not know that he’d been shown such a “sannyasin” as that (p. 170) before he left and that such a wandering ascetic then became a kind of model for him – i.e., that he wasn’t the first in his culture to do such a thing.

I did know that Siddhartha’s primary concern (and, therefore, later, Buddhism’s) was “searching for a solution to the problem of human suffering” (p. 171). And while I vaguely remembered something about a “Middle Path,” I couldn’t recall just what it was – i.e., that it’s basically finding contentment in having “just enough” to be happy and by doing so it would “solve the problem of suffering” (p. 171).

I was also aware that one tenet of Buddhism is that “all things are impermanent and ever changing” (p. 171). Nothing stays the same. That is a truth worth knowing. However, Prothero’s observation may be a bit of an over simplification, in my opinion, that Siddhartha’s central conclusion for why we suffer is that we wish the world would stay the same and not change (p. 171). There are more reasons for suffering than just that one.

I also knew that the word “Buddha” meant “One Who Is Awake” (or, as Prothero has translated it, the “Awakened One” – implying some cause for “waking up”). In that sense it’s a philosophy of waking up to a deep truth that then sets you free of desiring more. More what? That seems to differ with every human being. What does anyone need to be happy – or at least content with life and it’s impermanence?

If there’s one thing that I may “‘know’ differently” now it’s a deeper appreciation of what Buddhism has in common with philosophy itself. As a teacher of English (and so very much a “word person”) I know that the etymology of the word “philosophy” is that it’s derived from the two Greek words for “love” (philo) and “wisdom” (sophia) – so philosophy itself is the love of wisdom as well as the blending of both love and wisdom together. This seems to perfectly describe what Siddhartha “woke up” to and what released him from his suffering. For the rest of his life he tried to model what it meant to simply love others unconditionally. The level of his compassion became legendary – so much so that he attracted devoted followers. And the legend became a religion.

2 – What have you learned about Buddhism from popular media? 176

In a word: nothing.

3 – What Buddhist meditations have you tried? 178

I guess that I use anapanasati – “breath mindfulness” (p. 357, note 8) – most often simply to calm myself. I use it as a technique toward full-body relaxation when I’m doing yoga, but I’ve also used it to help “switch my mind off” in trying to relax into the time of sleep late in the evening.

I suppose that I use vipassana – or “mindfulness” – most often as a way of trying to silence “the monkey mind” (the chittering away of my own self-centered thoughts) and empty my thoughts as much as possible so that I might be open to whatever comes. I’ve used this as a sitting meditation, but I’ve also used it outdoors (most often when I’m kayaking by myself) so that all of my senses might be more open to whatever presents itself to me. I find this kind of focused “paying attention to what is” to have been the most helpful. It’s led to what I’d claim to be deeply mystical moments.

A version of this may be the Soto Zen term shikantaza – a practice where you just sit, without thinking, and empty yourself of any self-centered concerns (cf. p. 192). Typically, though, this has been the most difficult kind of meditation for Westerners as we find it very hard simply to be still. All too often we want much of life to be about solving problems, about getting up and doing things. In opposition to that urge, I’ve found it helpful to simply say to myself: “Don’t just do something. Stand there.” I often have been in awe at what has come to me out of such moments of stillness.

4 – The “self is a figment of the imagination.” Comments? 179

I think that this may be the one thing about Buddhism that I cannot accept. That the essence of who I consider myself to be really doesn’t exist at all seems ridiculous to me. I can’t even see how that might be useful – in the sense that Prothero observes there that Buddhists believe “their teachings are true only insofar as they are useful.” It may make sense in some kind of koan-like way that if “the self does not actually exist” then you also eliminate the one who is suffering. But then it eliminates all of who one is and, indeed, reality itself. So I’m with Descartes (“I think, therefore I am.”).

5 – Does the Eightfold Path imply that we should stifle our emotions (entirely)? 183

I don’t think so. To begin with, I like Prothero’s shorthand version of the Eightfold Path here: “be kind, be wise, be mindful.” How can anyone be compassionate, wise and deeply aware without being in touch with one’s emotions? It’s simply not possible.

Footnote number 11 (from p. 179 and noted on p. 358) may be helpful here. It’s not that we’re meant to stifle our “desire,” just our “craving.” Selfish and desperate longing can be irrational, but a profound longing for wholeness, well-being, harmony…peace (i.e., the essence of shalom), that kind of desire “can be a teacher.”

6 – What do you do to eliminate suffering? Does it work? 187

I find ways to constantly (i.e., in a mindful way) remind myself that I have everything that I need to be happy. I do have health concerns. I do have limited financial resources. But I have a comfortable place in which to live. I find many ways to love and to feel that I am loved in return – not just by my wife, my family and my friends, but by the natural environment itself. I am surrounded by beauty. I listen to it. I smell it. I taste it. I see it. I feel it deeply. I long, deeply, for more of the same – and because I do, more of these same kinds of good things present themselves to me. I am blessed.

7 – How do you feel or think about koans? 192

The most clever and ingenious koan can be much like a parable – i.e., the “answer” is often the one that you least expect. If for no other reason a koan can simply push you into more profound moments of contemplation because they do seem like puzzles with elusive or seemingly impossible solutions. And yet I think they can lead one onto divergent paths that will lead to satori – exactly those flashes of intuition or “moments of awakening that bring qualities of spontaneity and openness to everyday life.”

They can, however, frustrate a strictly rational person [Isn’t that right, Peter?]. As Prothero points out: “Apparently you need to wear out the left side of the brain so the right side can do its work. … You can’t think your way to nirvana; it comes when you are out of your mind” (p. 193).

8 - “Trust only what you yourself have seen to be true in your own experience.” Comments? 199

I think Prothero’s right here that “more than belief, Buddhism is about experience.” Its “teaching of emptiness…is a teaching of freedom.” But it’s the kind of liberation “from enslavement to people, judgments, objects, and ideas.” It leaves one open to…a different point of view…something else…something More.

There is a part of me, though, that can’t quite agree with Prothero’s conclusion here that “anything that comes to you secondhand is worse than worthless” – or the second half of that quote – “trust only what you yourself have seen to be true in your own experience.” Maybe it’s just my objection to such absolute language. I don’t think that I need to jump out of an airplane without a parachute to discover for myself that such a foolish decision will kill me. On the other hand, I did learn as a child for myself that falling from a great height can hurt. Is that the point?

If a truth comes to me “secondhand” and I explore it enough to embrace it – to make it my own – that it arrived secondhand doesn’t, by virtue of a circuitous route, automatically make it “worthless.” That I discovered the truth of it for myself should not negate my “trust” in that other source that initiated my exploration in the first place.

There must be a koan for this.

– “How can I fill my cup until I first empty myself of myself?”

– Or, how about this one: “The Kingdom of God is within you.”

Week 4 Questions

Hinduism

1 – Which description of the Hindu gods explained in the second paragraph on p. 134 do you prefer? Why?

2 – How much do you believe in reincarnation? 136

3 – How important is order to you, or how comfortable are you with chaos? 140 (How should order be obtained?)

4 – How do you believe in souls? 147

5 – What do you get with / in moksha? 147

6 – How have you tasted the salt water? 150

7 – What do you think is the benefit of all the complexity and diversity of Hinduism? 158

8 – What is the content of Hinduism? 164

9 – Is all religion (including Hinduism) simply a vehicle for each person to make their own impression on the world? up to 168

My Responses to Week 4

Week 4 Questions

Chapter 4 – Hinduism

1 – Which description of the Hindu gods explained in the second paragraph on p. 134 do you prefer? Why?

Most of their deities just seem bizarre to me. I would agree with those Hindus that see them only as symbols anyway – pointing to a deeper Reality. So I lean toward the group that simply says “there is no god whatsoever – that the gods are a by-product of our hyperactive imaginations.” This seems especially true, for me, given the bizarre pantheon posited by many Hindus.

On the other hand, I remain fascinated by, and so continue to consider, just who or what was and is the Prime Mover/Creator of all that is (I still don’t believe that it all came about by accident.). If that is my “god,” it’s without form or image and more like an inexplicable Force with which we can either cooperate and so flourish and grow or ignore at our peril (in the “Don’t-mess-with-Mother-Nature” sense).

2 – How much do you believe in reincarnation? 136

While it is fascinating to consider, I do not believe in reincarnation at all – but I have no way of knowing either way. I have been known to say, however, that if reincarnation were true, and if I were restricted to choosing to return only as some kind of animal, I’d probably choose to be a wild dolphin (emphasis on “wild” because I can’t stand those captives held at places like Sea World).

3 – How important is order to you, or how comfortable are you with chaos? 140 (How should order be obtained?)

I think Prothero’s discussion of chaos actually begins on the following page [p. 141] i.e., that “this first of religions begins by attacking the problem of disorder.”

While creation itself is not without disorder (e.g., “chaos theory” – that small alterations can give rise to strikingly large consequences), most of the disorder and chaos that we human beings struggle with are of our own making. Bringing order out of chaos, however, isn’t just “a political task to be undertaken by secular means,” it’s also “a religious burden.” It’s both because both have an effect on whether there is order or chaos (e.g., consider the events currently affecting the Middle East). So I disagree with Prothero’s shaping of the two as separate.

I would disagree, as well, “that ritual is the glue that holds society together” [p. 141]. Ritual is all too often nothing more than stylized acts pointing toward a deeper Reality that many religious people think is in control of things. Again, more often than not, we are the ones who create the chaos and disorder.

All things considered, I’d choose order over chaos anytime. I can’t stand for things to be out of control – not just out of my control, but totally out of control. To my mind order can only best be obtained and maintained through intelligent decision making – i.e., based upon compassionate concern for our environment, cooperation with others, and guided by scientific discovery.

4 – How do you believe in souls? 147

I don’t know “how” – intuition maybe. But when I look into another person’s eyes (or into the eyes of any sentient and intelligent creature for that matter), there seems to be a “soul” there – i.e., a spiritual entity distinctly separate from the body which embraces life, feeling, thought and action. When a person (or some other soulful creature) dies, it’s gone. Gone where? Who knows? And as I don’t believe in the traditional concepts of “Heaven” and “Hell,” I simply don’t speculate too much about “life after death” and the state of “disembodied souls.” To me all of that is pure speculation.

So I can’t quite get my mind around the philosophical Hindus who claim here that “there is an unchanging and eternal soul. And we are that soul.” What does that mean?

5 – What do you get with / in moksha? 147

What you get is “liberation from ignorance” and so I like that idea. I’m also intrigued, though, by the concepts of karma and rebirth – but not in any “woo-woo” life-after-death sense. Karma and rebirth constantly present themselves at almost every moment of our lives. Setting aside circumstances and outside forces for the moment (i.e., circumstances and forces beyond our control), much of what we experience in this life as “good” or “bad” is often a result of our own actions or failure to act – thus karma. I lean toward philosophical Hinduism in that regard, I guess, in that none of this comes from the outside (from gods, spirits or through ministrations by priests), but “by your own efforts and by your own experience” [p. 148]. If there is a “rebirth” it’s as we get many chances to get it right – but in this life, not in any next one.

6 – How have you tasted the salt water? 150

I agree that one attains “liberating wisdom” only through lived experience. It isn’t just given to us. I must admit, though, I have been given many opportunities and have benefited from the assistance and guidance of many wise teachers (gurus, if you will) throughout my life. They began with my father and grandfather, but continued through teachers, pastors and friends who crossed my path. I am deeply grateful for having paid attention to them. In the end, though, I could only achieve the “taste” of this “salt water” by my own responses and through my own efforts. Except for the accident of being born into a wonderful family and to have benefitted from a comfortable socioeconomic status, much of this wasn’t just handed over to me. For the most part, I could either accept it or reject it – make what I valued of it my own, “tasted the salt water” myself.

It’s all shaped me into the Liberal/Progressive that I am.

7 – What do you think is the benefit of all the complexity and diversity of Hinduism? 158

A simplistic answer might be that it just gives you many choices amongst a plethora of religious possibilities. And as a heretic (in the original sense), I will always want to be able to choose. It’s one aspect that defines my very humanity. I will always struggle against those forces that would try to take away that power to choose from me.

If there is any “benefit of all the complexity and diversity of Hinduism,” then, it might be that. However, because so much of Hinduism (like most religion) is myth and legend, it makes its “benefit” questionable in any existential sense. Life and ongoing creation are “beneficial” in and of themselves without any need for proof-texting either with this-or-that kind of religious belief.

8 – What is the content of Hinduism? 164

At its essence it might be described by a clothing analogy: “whatever fits wear it.” If you don’t like it, or if it feels uncomfortable, drop it and move on to something else that does fit and feel comfortable to you – i.e., that aligns with your own beliefs, values and point of view and helps you understand and appreciate the nature of reality.

I do like Prothero’s observation there, however, that “Hinduism divinizes human beings, but…also humanizes the gods.” How I hear that is illuminated by a comment that he makes on the very next page: “…no one religion has a monopoly on religious truth. All religions are flawed human efforts to capture the elusive divine” [p.165]. I agree.

9 – Is all religion (including Hinduism) simply a vehicle for each person to make their own impression on the world? up to 168

I’m not sure what you mean by the phrase “on the world” – maybe “of” the world might be more helpful.

Religion, however, has and will always be more than any one person or culture’s impression on or of the world. Its roots are in cultures and people as diverse as the societies and geography that make up the entire world. Separate religions, then, are the result of diverse people trying to make sense of “their” world – the world as they’ve experienced it, how they’ve come to know it, and what they value about it.

If you mean by “on,” a religion’s actual effect on the world, that would imply that religion is an attempt to affect the outcomes of our experiences in it. In that sense then, yes, I suppose many religions do try to shape their experience of the world in ways that align with what its adherents consider most important about it – what they ultimately value.

Week 3 Questions

Confucianism

1 – What do you think causes three Chinese religions to cooperate and three Abrahamic religions to compete instead? 103

2 – How well does the quote from Chi-lu fit into your religion? 107

3 – What would the combination of ethics and ritual look like in Christianity? 109

4 – (Extra Credit) Are Confucians more extroverted than U. S. Christians? 111

5 – How close are you to attuning duty and desire into one voice? 114

6 – Li or ren, which do you think is more important, and why? 118

7 – How well does Confucian Christian resonate with you? 124

8 – What is virtue? 126/7

9 – How is Jesus (or Christ or Jesus Christ) “a model we can emulate instead of a simply revere.”? 129

10 – Why did our author assign “propriety” to Confucianism rather than “community”? 130

Week 3, Confucianism

I'm getting the hang of this website now....

5. Duty and desire in one voice. That fits into the Christian/Jewish tradition rather well where we read, "I will write my Law on to their hearts." In other words, that virtue has its own reward; people should be "righteous" because they would feel shame for not doing so. Or, as Lincoln was reported to have said, "When I do right, I feel good; when I do wrong, I feel bad." I wonder if he really said that. It sounds pretty "California!" I like it, anyway.

8. Virtue. Such an easy question! (ha!) Acting ethically. The best definition of that for me is Kant's Categorical Imperative: "What would happen if everyone did it?"

9. Emulate Jesus, or revere him? When I began a Bible study in the county jail, I quickly learned that theology was a quicksand. Too many theories, many of them quite strange. So I simply went though the Gospel of Luke and we discussed what Jesus did and said. For me, it made a huge difference to study the man rather than interpretations of the man. I now conclude that to be a Christian, one should "walk in the footsteps of Jesus (not Christ)."

My Responses to Week 3

Week 3 Questions

Chapter 3 – Confucianism

1 – What do you think causes three Chinese religions to cooperate and three Abrahamic religions to compete instead? 103

Chinese religions seem to be more metaphysical (i.e., abstract, subtle, mystical, transcendental) and poetic to me, whereas the so-called “Abrahamic religions” appear more concrete and law-driven. What’s more, if you’re more interested in maintaining an open dialogue (e.g., Chinese) than you are in proclaiming your own point of view (e.g., Abrahamic), there will be greater cooperation – as our author points out the Chinese saying here: “Every Chinese wears a Confucian cap, a Daoist robe and Buddhist sandals.”

On the other hand, anything that is the least bit driven by commandments and legalities is bound to be drawn into competition with its neighbor (e.g., the Jewish Talmud which is primarily about instruction) because you’ll always want to prove that your point of view is right and the other’s is wrong.

2 – How well does the quote from Chi-lu fit into your religion? 107

I hear this quote saying that if you’re having difficulty dealing with what you know, how can you expect to grasp what you cannot know? I would agree with that. Speculations about other-worldly aspects of creation or life-after-death should remain just that: speculations – i.e., subjects of conjecture and personal opinion.

As Prothero points out there, this is why Confucianism is so often considered to be “a thisworldly religion – an attempt to find the sacred hidden in plain sight.” So I would agree with his further point: “There is a persistent, unexplored bias in the study of religion toward the extraordinary and away from the ordinary.”

3 – What would the combination of ethics and ritual look like in Christianity? 109

In short, whatever we’d be doing, saying, singing or praying about in our ritual would be not just what we believed but the way we acted. It would be a profound test of Luke 6: 27-36 (which begins with “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you” [v. 27] and ends with the classic “Do to others as you would have them do to you" [v. 31].

I really like what Prothero says there, then, that “virtue needs a neighbor.” It’s easy to claim that you’re a virtuous person. The hard test of that claim is living with reality and so dealing with world-views (and the people who have them) that are radically different from your own. So, if your ethics and ritual don’t seem to match, what you end up with are people that have been labeled “Sunday-morning Christians” – those whom you wouldn’t recognize as Christians outside of their staid responses to the rituals of Sunday morning worship.

While it may not be true for every Confucian, Tu Weiming’s pronouncement there rings true to me: “self-transformation…is a communal act.” As Prothero pointedly put it: “We become human by becoming social.”

4 – (Extra Credit) Are Confucians more extroverted than U. S. Christians? 111

There’s no way of being able to prove that glittering generality. Being an introvert or an extrovert is simply a personality trait. It has nothing to do with one’s religious beliefs.

5 – How close are you to attuning duty and desire into one voice? 114

I don’t know what gave rise to this question, but I do like Confucius’ statement there when he says, “I have transmitted what was taught to me….” We should do the same. In that sense duty must be attuned to desire because it’s simply something that we ought to do by virtue of our understanding of morality and longing for a better life.

6 – Li or ren, which do you think is more important, and why? 118

As I understand the term, li, it simply means doing what you know is the right thing to do in any given circumstance. And I like to think of ren as the kind of compassion that strengthens community, but it has to begin within the family. It begins early as we teach a child to move out of their natural self-centeredness into caring for others beyond themselves.

I can see why Prothero would note that “at the heart of Confucian ethics is the virtue of ren” [p. 115]. I would agree. You’ll never know right from wrong without learning to appreciate and then embody ren. Our community, country, nation and, indeed, our world will be better when we’re able to empathize with others needs and aspirations and help them realize those needs and aspirations as much as we desire them ourselves.

7 – How well does Confucian Christian resonate with you? 124

I don’t know Robert Neville, but I think that I can understand why he’d label himself as a “Confucian Christian.” As I understand it, a tenet of his duality is that we are co-creators with the Divine Creator. In that sense (as has been said), “the only hands that God has are our hands.” It’s up to us to realize “heaven on earth.” No savior will magically appear to provide it for us. We serve whatever we name as Sacred with compassion, common sense and the help and revelations of science.

I would disagree, however, with the supposed doctrine from both religions claiming that all human beings are essentially sinful. And yet neither are we essentially good. We must be carefully nurtured and taught. If there are any innately evil human beings, they’re insane.

So I like Prothero’s observation that li and ren are “two sides of the same coin” [p. 118]. It’s how I’ve come to understand the Hebrew concept of shalom. But shalom is like a many faceted jewel and not just with two sides. Yes, it is peace, but it also refers to concepts such as wholeness, harmony, health and, indeed, self-actualization – in the sense of doing all that we can as we become the kind of person we were meant to be.

8 – What is virtue? 126/7

I think that it begins for Prothero here in the ways in which “Confucius redirected our collective attention from the solitary individual to the person in community.” This is especially true in learning early on to “defer to those who know more than we do.”

In the end, though, virtue must mean conforming your life to situational but concrete ethical principles – i.e., knowing the difference between right and wrong at any given moment, and then having the moral courage to choose and act upon what the situation tells you is the right and good thing to do.

9 – How is Jesus (or Christ or Jesus Christ) “a model we can emulate instead of simply revere.”? 129

The short answer would be to act as he acted and love as he loved (Think of Bob Funk’s classic book published back in 1998: The Acts of Jesus: What Did Jesus Really Do?.). He did not walk on water, feed a multitude, change water into wine, or raise Lazarus from the dead. He was executed as a public nuisance, not for claiming to be the son of God…and he certainly did not rise bodily from the dead.

What Jesus did was show us how to live. We ought to be able to do the same within the limits of our own life. What’s more it should be a lot safer for us in this day and age than it was for Jesus. After all, I can’t see any of us being crucified just for being a public nuisance.

10 – Why did our author assign “propriety” to Confucianism rather than “community”? 130

As I understand Prothero’s use of the word, “propriety,” it’s to live a good, right, and just life. That would include, it seems to me, “how to become a human being.” The assumption is that you cannot be fully human in isolation; you must engage with life in community. So, in that sense, I think that Confucius may very well have agreed with Wendell Berry who argued that “only in community…is it possible to become fully human.”

Week 2 Questions

Chapter 2 - Christianity

1 – How do you feel (or, what do you think) about the huge diversity in the Christian church? 67

2 – Any explanation of the trinity you can understand is heresy. Comments? 69

3 – Which part of the “broader Jesus story” do you like best and worst? 72/3

4 – Where do you stand on the question of “faith and works” vs. “faith alone”? Did that question have anything to do with your choice of church or denomination to attend? 76

5 – Who gets to determine what is “true religion” and what is superstition, and why? 81

6 – How do you understand the difference between inspiration and infallibility? 86

7 – List, in order, elements of Christianity with which you are most and least comfortable. 88

8 – Do you have a preferred order for the four pillars of Methodism? What is it, and why? 91

9 – Why do you think Christianity is moving South? 95

My Response to Week 2 Questions

Chapter 2 – Christianity

1 – How do you feel (or, what do you think) about the huge diversity in the Christian church? 67

I not only agree that “the diversity inside Christianity alone is staggering” [p. 66], I think it’s the only reason Christianity still exists. Every time ecclesiastical hierarchies have wanted to impose their own version – through doctrine, liturgy, and dogma – some kind of separation has happened and that choice for diversity has kept the faith alive in a new way.