This book study begins January 10, 2021 only on Zoom.

Why did Jesus happen when and where he happened? Why then? Why there? Sharpen the questions a little. Why did two popular movements, the Baptism movement of John and the Kingdom movement of Jesus, happen in territories ruled by Herod Antipas in the 20s of the first common-era century? Why not at another time? Why not in another place?

Imagine two ways of answering those questions: by stone or by text, by ground or gospel, by material remains or scribal remains, by the work of the archaeologist or the work of the exegete.

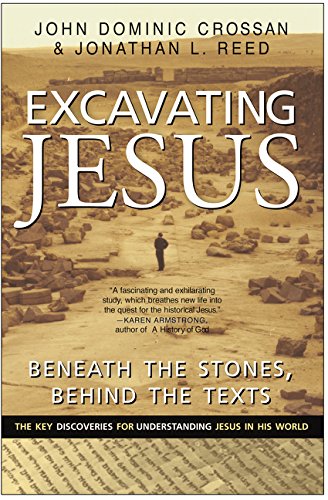

The premier historical Jesus scholar joins a brilliant archaeologist to illuminate the life and teaching of Jesus against the background of his world. There have been phenomenal advances in the historical understanding of Jesus and his world and times, but also huge, lesser known advances in first–century Palestine archaeology that explain a great deal about Jesus, his followers, and his teachings. This is the first book that combines the two and it does it in a fresh, accessible way that will interest both biblical scholars and students and also the thousands of lay readers of Biblical Archaeology Review (150,000+ circulation), National Geographic, and other archaeology and ancient history books and magazines. Each chapter of the book focuses on a major modern archaeological or textual discovery and shows how that discovery opens a window onto a major feature of Jesus's life and teachings.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Week 7 Questions

1 – Compare the mausoleum of Augustus to modern presidential libraries. 234 / 276

2 – Comment on the differences between the death of Augustus and Herod. 237 / 279

3 – How about a comparison of modern with ancient <burial> or whatever end-of-life practices. 244 / 287

4 – What kind of preparations have you made for after death? How much do you care about what happens? 246 / 290

5 – Anthropologists often use the findings of usable tools in ancient graves as an indication that the culture believed in an afterlife. What other things could the buried tools indicate? 255 / 299

6 – Is there any way the “justice” discussed in connection with resurrection can be seen as distributive justice and not retributive justice (or any other kind)? 258 / 302

7 – Is there any way that you can understand resurrection that makes sense? 260 / 304 (I’m a scientist, convince me or offer a demonstration.)

8 – How do you understand apocalypse now? 262 / 305

9 – Do you see a world under transformation by Christian cooperation with divine justice (and therefore accept Crossan’s version of Christianity)? Evidence? 270 / 314

10 – Can you envision any way other than (distributive) justice or power for ruling the land? 274 / 318

11 – Are modern, first world countries too rich for what Jesus was proposing: go into the world to heal and eat together? 276 / 320

12 – A final comment on the book? (last page)

Responses to Questions for Week 7

Chapter Six: “How to Bury a King”

1. Compare the mausoleum of Augustus to modern presidential libraries. [p.234]

There’s really no comparison. As our authors point out, (1), “Augustus’s mausoleum placed him atop the pinnacle of the social pyramid” [p.231]. Most presidential libraries just place them alongside other notable persons scattered about the countryside – most of them either famous celebrities or titans of industry. None of them have the stature of an emperor of ancient Rome. (2) “Augustus put up a spectacular façade of monumental proportions on his sepulcher” [p.232]. Ronald Reagan at least stuck the Boeing 707 that served as Air Force One for him in his building, but most of it – very much like all of the rest – are just museum galleries. (3) “Augustus’s mausoleum immortalized his legacy and dynasty in Rome” [Ibid.]. To my mind, only Washington and Lincoln have come close to that legacy – and neither of theirs is memorialized in a “presidential library” but in really colossal monuments. Finally, Augustus was the kind of imperial monarch who truly wanted later generations to understand this: “That is how you bury a king” [p.234]. None of our presidents ever established anything close to the kind of kingdom created by the emperors of ancient Rome.

2. Comment on the differences between the death of Augustus and Herod. [p.237]

Again, as our authors point out, Herod the Great may have been a great imitator of Augustus, but his constructions were really only “a signal to Jerusalem about who was in charge at society’s pinnacle” [p.235]. Augustus Caesar was way above and beyond that. As William Shakespeare had Cassius say to Brutus about another other Caesar, named Julius:

“Why, man he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonorable graves.”

[- Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene II]

You could never imagine anyone saying that in reference to Herod – even though some came to refer to him as the Great one.

3. How about a comparison of modern with ancient <burial> or whatever end-of-life practices. [p.244]

Most ancient burial practices – especially those worthy of attention – were more concerned about life-after-death and surrounded the dead with all of the trappings and finery one would expect for that journey and subsequent arrival. I know of no one in their right mind here in the modern world who expects to be resurrected in such an afterlife. We’ve even no proof in this day and age of the reality of an immortal soul – although many still wish it were so. So, most bodies today are either burned, buried or turned over for scientific research and only live on in the monuments of someone else’s memory. It’s even been said that a “second death” occurs when there’s no one around any longer who remembers the one who has died.

4. What kind of preparations have you made for after death? How much do you care about what happens? [p.246]

I’ve suggested to my family that if they can find no good use for my body, it should be cremated and my ashes be put to good use as mulch somewhere – preferably under a newly planted tree. But I’d be just as “happy” to have my ashes scattered in one or more of the waterways around the Pacific Northwest – places where I spent so many wonderful hours in my kayak while I was alive. We did this with the cremains of my father and two older brothers. In the end, I don’t much care what happens – except that I not be forgotten (that “second death”) but be remembered with gratitude by those I’ve loved and who’ve loved me in return.

5. Anthropologists often use the findings of usable tools in ancient graves as an indication that the culture believed in an afterlife. What other things could the buried tools indicate? [p.255]

Tools buried in an ancient grave could also indicate the vocation of the deceased – i.e., that these were the tools that he or she used in life and helped define who they were when they were alive.

6. Is there any way the “justice” discussed in connection with resurrection can be seen as distributive justice and not retributive justice (or any other kind)? [p.258]

I think that our authors make this point there when they say:

• “There must be a time and place of justice for the persecuted.”

• “...that hope went out to all the just, to all those who had lived for justice or suffered from injustice.”

So, it isn’t always just “getting even” or punishing the perpetrators of injustice, but rewarding everyone equally who “kept the faith” and carried on in the face of a seemingly hopeless situation.

7. Is there any way that you can understand resurrection that makes sense? [p.260]

Certainly, from a scientific point of view, a bodily resurrection makes no sense at all. It doesn’t happen. It never did. Those Jesus followers who invented it possibly wanted to go one better than the claims that were being made by those other “sons of god,” the emperors of Rome. More importantly, however, is how our authors (principally Crossan, I’m sure) point out that resurrection had to be claimed by the nascent Christian church as the beginning of a new day or Jesus’s death would’ve been in vain. It gave the Jewish peasantry hope – if not in their own lifetimes, then in the next. As our authors note:

• “The Jesus resurrection and the general resurrection stand or fall together. ...they are the beginning and end of a single process” [ibid.]

• It is “...the final moment when a God of justice publicly and visibly justified the world, turned it from a place of evil and violence to one of goodness and peace. To announce the resurrection of Jesus was to claim that such an event had already started” [p.261].

8. How do you understand apocalypse now? [p.262]

It was (and, for some, still is) the last hope of a people crushed by the ongoing reality of violence and injustice in their world; it’s their answer to the question posed by theodicy: “If God is a god of love, why is there evil?” And if they weren’t receiving a satisfactory answer in their lifetime (“instantive”), God surely must be about working it out eventually (“durative” – i.e., as “an ongoing process” over time).

Paraphrasing the words of The Rev. Theodore Parker – a Unitarian minister and prominent abolitionist from an earlier generation – The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. once famously said that “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” As I’ve said before, however, I’ve become convinced that nothing like that will bend without us doing the bending. The only “hands” God has are our hands; or as Walt Kelly’s cartoon character, Pogo, said decades ago, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

9. Do you see a world under transformation by Christian cooperation with divine justice (and therefore accept Crossan’s version of Christianity)? Evidence? [p.270]

Let me say, at the outset, that I disagree with Crossan’s earlier conclusion that “Jesus was raised from the dead by divine power. [And that event] “is, in fact, the heart of Christian faith” [p.231]. My faith doesn’t stand or fall on that proclamation, because I simply do not believe that it ever happened. I don’t know that Crossan believes that it ever happened either. I am persuaded, however, that to do what is right is to do what is just [cf. p.273]. If it means putting our faith in some form of “divine power” behind us – helping us all to do that – then I would want to be aligned with such a power. The only evidence that I can point to is that we have learned – somewhere, somehow, and from somebody – what is right and just and what is not. All that we need now is the will to pursue it with every fiber of our being. If the Kingdom of God as envisioned by Jesus helps us get there, then I want to be part of it. That, fundamentally, is why I joined the United Methodist Church. That is why I became ordained.

Epilogue: “Ground and Gospel

10. Can you envision any way other than (distributive) justice or power for ruling the land? [p.274]

If there’s a better way, then I’d like to see it. At the very least, a local, regional, national, and global system of distributive justice would be a good beginning. I just don’t think that you need to insist upon “divine ownership” [p.275] of it all. The danger of that conclusion is then having someone with real power define the nature of that divinity for us – like a Roman emperor, a Pope, Bishop, ...even a pastor – because holding such power has (all too often) led to the perverted use of it. Our system of democracy in this country at least has been a system intended to be “of the people, by the people, for the people” alongside the kinds of checks-and-balances that would avoid having all of the power held only by a handful of elites. So, it’s still a work in progress and we’ve a long, long way to go.

11. Are modern, first world countries too rich for what Jesus was proposing: go into the world to heal and eat together? [p.276]

Sadly, we are a long, long way away from the kind of egalitarian society Jesus was proposing. But wealth, alone, isn’t the reason why it’s not working. It’s those that hold the power (and, yes, much of the wealth) that have refused others equal access to it.

12. A final comment on the book?

All of the prognosticating about resurrection aside, I still think that the life and teachings of one Jesus of Nazareth are worth following. Finally, I believe Crossan has it right when he speaks about Jesus and his kind of kingdom building:

“The Kingdom of God, in other words, was not just a vision but a program, not just an idea but a lifestyle, not just about heaven hereafter but about earth here and now, and not just about one person but about many others as well. ... He said: do it, just do it.” [p.275]

Week 6 Questions

1 – How do you think the difference between the monarchy and the priesthood compare with the U. S. separation of church and state? 183 / 225

2 – What is one important characteristic of: Essene Judaism, Pharisaic Judaism, Sadducean Judaism and (if you can figure it out) Fourth-Philosophy Judaism? 184 / 226 (Read further for more details.)

3 – What are the advantages and disadvantages to destroying the Temple? 186 / 228

4 – How would you compare the first (66 – 74 CE) revolt with the storming of our capital on Jan. 6? 188 / 230

5 – If you can remember what we discussed / learned from Resa Aslan’s “Zealot”, compare that description of Jesus with the Zealots mentioned here. 191 / 233

6 – What do you think about “casting lots” to determine an outcome? (both ancient and modern) 191 / 233

X – To get some local idea of the size of the Temple, I used Google Earth. Kathryn and I live near the Justin Sienna complex. From Solano to Maher along Trower is just over 1000 feet, and going up Maher 1550 feet gets us to the bus parking lot driveway. The northern most corner then includes most of the Watermark at Napa Valley retirement home.

7 – What do we have in the modern world that corresponds to the Gentile, Jew, Men, Priests, High Priest layers at the Temple? 198 / 240

8 – When did the Golden Eagle com and go? 200 / 242

9 – What is your opinion on both Entry and Clensing? Are they “historical”? Which (, 1 or 2) immediately caused Jesus’ death? 222 / 264

10 – How do you reconcile the Pilate of the Gospels with the Pilate of the “historians” 226 / 268

Responses to Questions for Week 6

Chapter Five: “Beauty and Ambiguity in Jerusalem”

1. How do you think the difference between the monarchy and the priesthood compares with the U. S. separation of church and state? [p.183]

There’s no comparison. As our authors point out, “both the Herodian and, later, the direct Roman rule treated the high priests like subordinate civil servants” [ibid.]. While many of our politicians are profoundly affected by their religious belief, at least we’ve not degenerated into some kind of theocracy as existed in 1st century Palestine.

2. What is one important characteristic of: Essene Judaism, Pharisaic Judaism, Sadducean Judaism and Fourth-Philosophy Judaism? [pp.184-193]

What distinguished the Essenes from others is that they lived in gatherings much like communes and dedicated themselves to poverty and asceticism. Like the Pharisees, the Essenes did meticulously observe the Law of Moses, the sabbath, and ritual purity and also professed belief in immortality and divine punishment for sin. But, unlike the Pharisees, the Essenes denied the resurrection of the body and refused to immerse themselves in public life.

What is most important about Pharisaic Judaism is that their belief system became the foundational, liturgical, and ritualistic basis for Rabbinic Judaism – the normative form of Judaism that came to be established after the fall of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE.

The Sadducees were the party of high priests and all of them were from aristocratic families – even merchants – so, the wealthier elements of the population. Unlike other religious leaders in Judaism, they were very much influenced by Hellenism and so tended to have good relations with their Roman rulers even, oddly enough, as they represented the more conservative views within Judaism. In that regard, one important characteristic of Sadducean Judaism is that they refused to go beyond the written Torah (first five books of the Bible) and, unlike the Pharisees, denied the immortality of the soul, bodily resurrection after death, and any thing like the existence of angelic spirits.

It was the Zealots who were also known as the “Fourth Philosophy” and their most important characteristic was their passion for liberty – i.e., “doing their own thing.” That led them to absolutely despise any Jews who sought peace and conciliation with the Roman authorities. They may have agreed with the Sadducees that there was no such thing as a soul which would still exist after death, but they didn’t believe in some kind of eternal punishment after death either. Beyond their passion to be left alone, I’d say that their one important characteristic is that they rejected the Oral law and focused, instead, on Temple worship.

3. What are the advantages and disadvantages to destroying the Temple? [p.186]

If you want to demoralize and then dominate a people, destroy the one thing that they love the most – that’s at the very heart of their life and faith. For the Jews, that was Jerusalem and their Temple. As the emperor Hadrian “Romanized the city,” he “eradicated all signs of Judaism” [ibid]. Advantage Rome. The disadvantage was that the Jews never forgot. They would get back what had been so cruelly taken from them. It’s not that they then fought long and hard for their freedom again, but through centuries of “covenantal protest” they would demand “divine justice” [p.188]. Did they get it? You tell me.

4. How would you compare the first (66 – 74 CE) revolt with the storming of our capital on Jan. 6? [p.188]

There’s no comparison. The earlier one was an uprising of an entire nation who’d experienced a crushing defeat by the world-domineering culture of Rome. The tragic incident of January 6, 2021 was no more than a bunch of disaffected white supremacists who blamed others for their empty lives and then allowed a humiliated fascist – under the grip of his narcissistic personality disorder – to foment them into a day of rioting and social disorder.

5. If you can remember what we discussed / learned from Reza Aslan’s “Zealot”, compare that description of Jesus with the Zealots mentioned here. [p.191]

As I recall, Reza Aslan argues that Jesus was a political, rebellious, and eschatological Jew whose proclamation of the coming kingdom of God was a call for regime change – for ending Roman hegemony over Judea and ending a corrupt and oppressive aristocratic priesthood. In short, he was a Jewish zealot.

Let me say at the outset, I disagree with him, but the central argument of Aslan’s book, "Zealot," is something like this: Jesus, like other messianic figures of his day, called for the violent expulsion of Rome from Israel. Driven by a kind of religious zeal, Jesus supposedly believed that God would empower him to become the king of Israel and overturn the hierarchical social order. According to Aslan, Jesus believed that God would honor the zeal of his lightly armed disciples and give them victory. Instead, Jesus ended up being crucified as a revolutionary. It was early Christians, then, according to Aslan, who changed the story of Jesus to make him into a peaceful shepherd and they did this for two reasons: because Jesus’s actual prediction had failed, and because the Roman destruction of rebellious Jerusalem in 70 CE made Jesus’s real teachings both dangerous and unpopular. What’s more, again according to Aslan, Paul radically changed the identity of Jesus from human rebel to divine Son of God – against the wishes of other leaders like Peter and James. It’s all fiction and history reimagined.

6. What do you think about “casting lots” to determine an outcome (both ancient and modern)? [p.191]

It makes as much sense as spending all that you have feeding a single slot machine at a casino and expecting that you’ll win all of your money back through prayer – because you believe that God’s on your side.

7. What do we have in the modern world that corresponds to the Gentile, Jew, Men, Priests, High Priest layers at the Temple? [p.198]

It’s called the caste system. It’s all there in Isabel Wilkerson’s stunning book, "Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents."

8. When did the Golden Eagle come and go? [p.200]

Herod the Great put it there “representing Roman domination and Jewish submission” [ibid.]. It must have happened sometime after retaking Jerusalem in 37 BCE and during his 33-year reign as king of Judea – remember, however, he ruled as a client of Rome. So, the eagle went up sometime during the 30s BCE. If the incident of its removal happened just before Herod’s death [p.199], it must’ve come down in 4 BCE – long before the first Jewish Revolt which happened a century after he died.

9. What is your opinion on both Entry and Cleansing? Are they “historical”? Which (1 or 2) immediately caused Jesus’ death? [pp.220-222]

I agree with Crossan’s conclusion that Jesus’s “triumphal entry into Jerusalem” is a myth – it just doesn’t sound like something that he’d ever do [pp.221-222]. However, it seems to me, that he would have done something like “cleansing” the Temple of those corrupt moneychangers because they had desecrated “a house of prayer for all the world” [p.220]. From his humble beginnings to his tragic end, that’s what Jesus was about: a reformation of Judaism – nothing more, nothing less. Neither one of these events, however, would have “immediately caused Jesus’ death.” Between Rome and their Jewish quislings in power, Jesus was just viewed as a local troublemaker and needed to be taken out of circulation.

10. How do you reconcile the Pilate of the Gospels with the Pilate of the “historians”? [p.226]

I imagine the Gospel accounts as religious theater. It was never written as history, and it was never meant to be read as history. So, even though we know very little of Pontius Pilate, the man, beyond his posting as prefect (or governor – c. 26-36 CE) of Judea under the emperor Tiberius, I’d trust the historians before I would the Gospel stories. Rome kept good records. As our authors note here, there’s that historic evidence that the Samaritans reported Pilate to Vitellius, the governor of Syria, after Pilate had attacked them on Mt. Gerizim in 36 CE [NOTE: I looked up the rest of the story.]. The rest of the record from "Jewish Antiquities" confirms that Pilate was then ordered back to Rome to stand trial for (get this!) “cruelty and oppression” – particularly on the charge that he’d executed men without a proper trial. What’s more, according to the historian, Eusebius, Pilate killed himself on orders from the emperor Caligula (That does sound like something that Caligula would do!). Pilate had finally run out of options.

Week 5 Questions

1 – What do you think the difference is between changing your religion in our modern era and changing your religion in Jesus time? 138 / 179

2 – Would you make a good martyr? And for what? 145 / 187

3 – Where are you likely to be on the multidimensional resistance spectrum? Do you feel you practice that now? 147 / 183

4 – Do you think Josephus is reliable or just the only source available or ??? 148 / 190

5 – What do you think would be labeled as pure or impure? How did it get that way? 151 / 192

6 – What personality trait do you think would be most distinctive in determining whether a person would wish to display or hide their social status? 157 / 198

7 – Does having God on your side give you a measure of hope? Any comments about this idea? 162 / 203

8 – Do you think Jesus (and followers) may have had any influence that helped pacify Sepphoris? 166 /206

X – For Bob: what can you tell us about working limestone on a lathe? 167 / 208

9 – If the miqwaoth “restor[ed] the individual’s place in the community of Israel under the covenant”, what do modern’s have / do that corresponds? 172 / 213

10 – How do you understand the debate about whether Jesus was an apocalyptic or non-apocalyptic figure? What does it mean? 174 / 214

11 – What do you think about the progression from nonviolence to defensive violence? 180 / 222

Responses to Questions for Week 5

Chapter Four: “Jewish Resistance to Roman Domination”

1. What do you think the difference is between changing your religion in our modern era and changing your religion in Jesus time? [pp.136-138]

Since religion was an integral part of one’s culture and customs during the 1st century CE, “changing your religion” essentially would mean rejecting every aspect of your being. It’s not likely to happen. The principle difference between then and now, is that’s no longer true in “our modern era,” where changing one’s religion is much more common – even trendy – particularly in the United States and in other, so-called, 1st world countries.

2. Would you make a good martyr? And for what? [pp.145 ff.]

I doubt that I’d ever walk boldly into becoming a martyr, and definitely not “for God’s sake” – whether or not that god were either understood as apocalyptic or nonviolent. That being said, I hope that I would put my life on the line for the sake of my family or for peace with justice, but I’d try every other path of resistance, first. I cannot imagine myself simply walking into the maw of lions as martyrs have done over the centuries – some even singing as they go. I think that I’d fight to my death before ever doing such a thing.

3. Where are you likely to be on the multidimensional resistance spectrum? Do you feel you practice that now? [pp.140-147]

I’m definitely neither a “Bandit” nor an “Apocalypticist.” I am closest to those who protest in the presence of hatred and injustice. However, I have to admit that I’m not among militant “Protesters” who intentionally get in-the-face of groups such as the Proud Boys (a truly unfortunate name), for instance, or who confront other white supremacists and anarchists. I protest to my legislators in hopes that they will be moved to “do the right thing.” I protest to my family, friends and the neighbors in our extended community. But, often that’s just like “preaching to the choir.” So, should I do more? Yes. Then, why haven’t I? Regrettably, it’s because I’ve not yet had the motivation or the will to do so – and I’m very uncomfortable about that indictment of myself.

4. Do you think Josephus is reliable or just the only source available or ??? [pp.139-148]

I think Josephus is reliable in some ways – principally because he was there – and yet in other ways he’s not. Because he was somewhat of a quisling and panderer to Rome, he’s not the best witness to “the Jewish problem” – even though he was Jewish, himself. He became an outsider. So, we are left with exegesis and archaeology – but even with those tools, we’re just “reading between the lines” about what actually happened with and to whom, when, and why.

5. What do you think would be labeled as pure or impure? How did it get that way? [pp.150-171]

Purity should be left to science. As I understand it, science explains it as the ratio of a named pure substance in any sample (by weight, mass, volume or count). It could be a number between 0 and 1 and expressed as a percent, fraction, or some other unit of fineness as when several units of purity is prescribed to precious metals. Purity could also be applied to things like gemstones – where a diamond’s purity is measured by its absence of blemishes. In somewhat the same sense, there ought to be scientific guidelines as to just what is or is not “pure” drinking water – that it’s free from anything that debases, contaminates or pollutes it. Purity can, and should, be applied to the food that we eat, as well – not on some mythical category, like holiness, but meaning that it’s unmixed, uncontaminated or wholesome.

Applying purity to the being and actions of people becomes problematic, at best – e.g., using it to describe the virtue of a young girl who remains a virgin, or as it may be applied to any other person who is driven to follow certain prescribed values set by the larger community. In the end, defining purity as freedom from spiritual or moral defilement – such as innocence or chastity – would be a misuse of the term. None of us could be pure. How did it get that way? The people (mostly male) in power defined it and then willfully imposed it upon others.

6. What personality trait do you think would be most distinctive in determining whether a person would wish to display or hide their social status? [p.157]

Anyone with NPD (Narcissistic Personality Disorder) wants to display his or her social status [...and in the last four years, or more, we’ve learned who’s done just that!]. On the flip side, anyone driven by fear will want to hide. Psychology teaches that fear is significantly correlated with the responsibility for bad outcomes and with the tendency to overly generalize all outcomes to many situations when one is afraid – and things just get worse as fearfulness increases.

7. Does having God on your side give you a measure of hope? Any comments about this idea? [pp.162-165]

This is simply a non sequitur for me. God only has a “side” as we have come to project it upon our concept of God. I do not. Now, in keeping with the teachings and actions of people whom I would call holy – like Jesus, Gandhi, the Buddha, the Dalai Lama, et al. – I am hopeful that attributes such as love, kindness and compassion, alongside the concepts of truth and justice, will prevail in the end. Again, however, it’s up to us, not God – i.e., “Where there’s a will there’s a way” is an obvious truth in this case. When paraphrasing the words of The Rev. Theodore Parker (a Unitarian minister and prominent abolitionist from an earlier generation) The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. once famously said that “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” That may, indeed, be true; however, I’ve become convinced that nothing will bend without us doing the bending.

8. Do you think Jesus (and followers) may have had any influence that helped pacify Sepphoris? [pp.162-165]

I don’t think Jesus or his followers “pacified” any region or group of people. If anything, they encouraged the populace to resist both the power and influence of Rome and the kind of Jewish leadership that bordered upon their being quisling supporters of Rome. So, Jesus did not bring or restore a state of peace or tranquility to Galilee. In no way would his actions and teachings have reduced his people to a state of submission – quite the opposite.

X – For Bob: what can you tell us about working limestone on a lathe? [pp.165-168]

Of course, I can’t speak for Bob (What do I know?), but since stone comes in varying degrees of hardness and fragility, it seems to me that you’d be able to use high speed steel to edge and smooth softer stone – especially if you were to use some kind of carbide and/or diamond-impregnated tools. If you can do it on marble and granite (and I think sculptors have), you could do it on limestone as well.

9. If the miqwaoth “restor[ed] the individual’s place in the community of Israel under the covenant”, what do modern’s have / do that corresponds? [p.172]

As our authors noted, these ritual baths were meant to be “a daily reminder of one’s tradition and covenant with God, an acknowledgment of God’s holiness and of Israel’s requisite purity” [p.170]. I think that our participation in many of the rituals at the heart of our worship (on Sunday morning, especially) do correspond to many of the beliefs and rituals that were part of the purity system in the Judaism of the 1st century. Some might just “go through the motions” during such rituals – then as now – and never ponder how they might move them to feel closer to God, but that’s not necessarily due to the inefficacy of the rituals themselves. When your heart is deeply touched by the presence of the Sacred, you will know it – and it doesn’t always happen in church.

10. How do you understand the debate about whether Jesus was an apocalyptic or non-apocalyptic figure? What does it mean? [p.174]

If Jesus was an apocalyptic figure, he would’ve believed that “God’s solution to evil [indeed was] the extermination or conversion of evil-doers” [ibid.]. In one of its more common understandings, we have John (a.k.a., the Baptizer) and his “vision of the imminent arrival of an avenging God who would eradicate sin and sinner alike” [p.178]. I don’t see Jesus as wanting to ever exterminate any human being; and I don’t think that he was some kind of an itinerant evangelist out to convert the gentile world. He was trying to bring his own people back to the heart of Judaism. And he wasn’t passive about it at all, but actively engaged with anyone and everyone he met to repent of their evil ways – to stop, turn around, and return to the God who is the essence of their faith (the literal meaning of the word, in Hebrew, teshuvah/ תשובה – translated as “repentance” – is the same as the one in Greek, metanoia/μετάνοια).

So, I tend to agree with Crossan’s conclusion that if Jesus really were an apocalyptic figure, Pilate would’ve seem him as a direct threat and “many of his companions would have been rounded up along with him and would have died beside him” [p.174]]. He was a figure at that “interface between covenantal community and martyrological protest” [loc. cit.].

11. What do you think about the progression from nonviolence to defensive violence? [pp.172-181]

I could see myself taking that step – if, in fact, active nonviolence failed and was always met with violent responses by those in power. Regrettably, however, in doing so I could not call myself a true follower of Jesus – nor of Gandhi or Martin Luther King, Jr. for that matter. So, I believe Crossan is right in concluding that “the first layer, the layer of the historical Jesus, is that earlier one of nonviolent resistance to injustice in the name of the Kingdom of God” [p.180]. So, by my being willing to take the next step of “defensive violence,” would that mean that I could no longer legitimately, then, call myself a Christian? You tell me.

Week 4 Questions

1 – What was a dining arrangement that you either A) liked or B) disliked? 98 / 136

2 – Why would lamps be offered at P(B)anias? 102 / 140

3 – In what interesting ways do moderns offer displays of wealth in their homes? 104 / 142

4 – How do you feel about my sitting at the end of the table for our final potluck? (pre ZOOM) 104 / 142

5 – I found the section “IN THE KINGDOM OF GOD” up to “Accusing Jesus about Food” to be vague and indirect. What do you think? 118 / 156

6 – Who would you, today, put into the category of “tax collectors and sinners”? 119 / 157

7 – What do you think transpired at the dinner of Jesus with “tax collectors and sinners (prostitutes)” that caused their “conversion”? 120 / 158

8 – Do you thin about “control [rather] than assistance” when you make charitable donations?What do you consider when deciding who and how to help? 121 / 159

9 – Jesus sent the disciples out “two by two”. What differences in society / culture would make their (ancient) endeavors any more (or less) successful than pairs doing this today? 126 / 164

10 – How concerned are you with “purity”, both in the author’s version and in the previous author’s version? 130 / 168

11 – From what culture did the Sibylline Oracles come? X / 172

12 – What may (will?) cause a (the) God of justice to die? 134 / 174

Responses to Week 4 Questions

Chapter Three: “Putting Jesus in His Place”

1. What was a dining arrangement that you either A) liked or B) disliked? [p.98]

I prefer dining arrangements that are small enough to be able to engage anyone and everyone in most of the conversations that go on around the table. If there are too many people, or the table is too long, the people at one end are never able to engage with those at the other end. A circular table that would accommodate ten-to-twelve people would seem to be ideal to me. The dining arrangement that I’ve disliked the most, however, is being forced to sit with or among people I do not like or with whom I’ve absolutely nothing in common. In that kind of a situation commensality is impossible.

2. Why would lamps be offered at P(B)anias? [pp.101-103]

They’re offered so no one would be left in the dark – literally or figuratively.

3. In what interesting ways do moderns offer displays of wealth in their homes? [p.104]

I’d say that they do this most often in displays of works of art – paintings or statuary – but also in an exquisitely-set dining table, sumptuously-furnished rooms, as well as abundantly lush gardens and grounds (surrounding the Ferrari and Aston Martin parked out front).

4. How do you feel about my sitting at the end of the table for our final potluck? (pre ZOOM) [p.104]

I simply feel grateful for all that you do for us, Peter. You are much more than simply our organizer and convener; you bake cookies! So, at our final banquet, it’s quite natural that – with Evelyn at your left hand – you both are our honored hosts; we are your grateful guests.

5. I found the section “IN THE KINGDOM OF GOD” up to “Accusing Jesus about Food” to be vague and indirect. What do you think? [pp.115-118]

I found that the paragraph introducing “Accusing John about Food” [p.115] was a good, if brief, summation of the theory of how the disparate gospels were created and are connected to each other. And the middle section at least gives us some insight into the importance of the Jewish historian, Josephus, as well as a better understanding of the apocalypticism of John the Baptizer and what he was up to. It’s not the best prose, though, I’ll grant you that.

6. Who would you, today, put into the category of “tax collectors and sinners”? [p.119]

...professional politicians and other such prostitutes who’ve sold their souls – for either power or monetary gain

7. What do you think transpired at the dinner of Jesus with “tax collectors and sinners (prostitutes)” that caused their “conversion”? [p.120]

Jesus stayed and made them feel welcome and included. Everybody else left.

8. Do you think about “control [rather] than assistance” when you make charitable donations? What do you consider when deciding who and how to help? [p.121]

I think about assistance first – i.e., that I can be given assurances that it will get to the people or causes that need it the most without it being depleted by intermediaries or the charity itself. In that, UMCOR is one of the best that I know of. Control is much less of a concern to me. I consider the most important thing is helping those who can’t help themselves.

9. Jesus sent the disciples out “two by two”. What differences in society / culture would make their (ancient) endeavors any more (or less) successful than pairs doing this today? [p.126]

For the most part, Jesus was sending his people out among their own people. Our modern society is far more diverse than it was in the Galilee of the 1st century. The only other difference that comes to mind is the feature of “commensality” – eating together at the same table without competing with one another or having different values or customs. Itinerancy might work for Mormon missionaries and other such evangelists, for instance, but I wouldn’t feel comfortable sitting down to eat with them, knowing full well that we have radically different values and very little in common – i.e. no commensality whatsoever.

10. How concerned are you with “purity,” both in the author’s version and in the previous author’s version? [p.130]

The only purity I’m concerned about has to do with the food that I ingest and the water that I use – for drinking, bathing, laundering and, occasionally, swimming in.

11. From what culture did the Sibylline Oracles come? X / 172

To begin with (according to Wikipedia), these “are a collection of oracular utterances written in Greek hexameters and ascribed to the Sibyls, prophets who uttered divine revelations in a frenzied state. ... The Sibyls were female prophets or oracles in Ancient Greece.” The best-known depiction of five of them can be seen in Michelangelo’s frescos on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel – where one is Delphic, one Libyan, one Persian, one Cumaean and one Erythraean. However (again, according to Wikipedia), these Sibyls could be “any of several prophetesses usually accepted as 10 in number and credited to widely separate parts of the ancient world (such as Babylonia, Egypt, Greece and Italy).”

12. What may (will?) cause a (the) God of justice to die? [p.134]

...when and wherever there is no justice.

Week 3 Questions

1 – Where have you found a kingdom of justice and nonviolence (if you have)? 51 / 89

2 – If what way(s) is our current kingdom (empire) different from the commercial or covenantal kingdom described? 54 / 92

3 – Do you know of anywhere the land still belongs to God? 70 / 108

4 – “inevitable human drive for fewer and fewer people to have more and more and more people to have less and less.” Is this so deeply embedded in our DNA as to be impossible to fix? 70 / 108

5 – Do you see the Democrats as the promoters of equality vs. Republicans as promoters of inequality? 70 / 108

6 – The idea of Jubilee, remission of debt every 7 (or 7X7) years is written in the Bible, but is an explicit example ever given? 73 / 111

7 – What is the time difference between Leviticus and Jesus? 73 / 111

8 – Do you find yourself reading the exegetical content with a more interactive approach and the archaeological content with a more one-way approach of simply soaking up the content (after looking up the terminology on wikipedia)? 90 / 128

9 – Does Luke’s use of synagogue-as-building argue for a later date of authorship? 91 / 129

10 – Does the Kingdom of God more closely match the life of modern homeless than it matches those of us with (fairly) secure homes? 96 / 134

Responses to Questions from Week 3

Chapter Two: “How to Build a Kingdom”

1. Where have you found a kingdom of justice and nonviolence (if you have)? [p.51]

I’ve not done any exhaustive research into this, but, regrettably, I think that “a kingdom of justice and nonviolence” only exists in our collective aspirations. We may be getting closer to realizing it in countries where progressive movements emphasize providing good education, a safe environment, and an efficient but fair workplace. None have made it yet; but that doesn’t mean we should give up and stop trying to make it happen. Unfortunately (as our authors point out), “...luxury increases at one end of society by making poverty increase at the other. The rich get richer as the poor get poorer” [p.53]. It may not be to the depth or extent that it was in the 1st century, but that separation, sadly, remains as true today as it did then.

2. In what way(s) is our current kingdom (empire) different from the commercial or covenantal kingdom described? [p.54]

The American empire is far more like Jeroboam’s model of a commercial kingdom than it does Amos’s model of a covenantal kingdom. Instead of a kingdom of justice and righteousness, it favors the prosperity of corporate big business, not the well-being of the average individual. It’s about building projects sprawling across the landscape that only benefit the wealthy at the expense of a quality of life for the average citizen. It favors tax shelters for the wealthy while imposing crushing debt on too many others. Much like the government of Herod the Great, America’s shelter for the wealthy elite has led to “Luxury increasing at one end of society [while making] labor and poverty increase at the other” [p.62]. In a covenantal kingdom, land and property would be distributed fairly and equitably among all the citizens of the country and everyone would face equal justice under the law. That’s just not so in America.

3. Do you know of anywhere the land still belongs to God? [p.70]

Okay, this sent me off on a wild Google chase: Nunavut in Canada (Auyuittuq – meaning “the land that never melts” – National Park), Hang Sơn Ɖoòng in Vietnam (one of the world’s largest natural cave system), the Namib Desert of Namibia, Bhutan (on the eastern edge of the Himalayas), the Rock Islands of Palau, the Star Mountains of Papua New Guinea, Fiordland in New Zealand, Daintree National Park in Queensland of Australia, Cape Melville of Australia, the Northern Forest Complex of Myanmar (which has the largest tiger preserve in the world), the Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park of Madagascar, the Seychelles, Northern Patagonia of Chile, the Sakha Republic and Kamchatka of Russia, much of the uninhabited Amazon Rainforest of South America, the tropical rainforest of the Congo Basin, Mount Namuli in Mozambique, most of Greenland and, of course, how about Antarctica?

According to another source, there are only five countries left in the world that hold 70% of the world’s remaining wilderness: the Boreal forest of Canada, much of the land along the Amazon in Brazil, the “outback” of Australia, Alaska’s arctic tundra of the USA, and then Russia with more wilderness areas than any other country on earth. Since it’s not part of another country, this category doesn’t include the wilderness of Antarctica. So, just 23% of the earth’s landmass can now be considered “wilderness” – which would be my own definition of land that “still belongs to God.” Most of the rest of it, sadly, has been spoiled – by us.

4. “...the inevitable human drive for fewer and fewer people to have more and more...and for more and more people to have less and less....” Is this so deeply embedded in our DNA as to be impossible to fix? [p.70]

That original quote, of course, was talking just about land, but speaking sociologically and economically, that dynamic remains to be deeply embedded everywhere within the people who hold the most power. But, I don’t think that it’s “deeply embedded in our DNA.” So, we can fix it – if we have the will. There is a way, then, but will we take it?

5. Do you see the Democrats as the promoters of equality vs. Republicans as promoters of inequality? [p.70]

I think that’s an overly pejorative comparison. I continue to believe that here must be a way to bring the best of both together – to reconcile right-wing and left-wing politics. We just haven’t tried hard enough yet to make it work. There must be ways of synthesizing center-right economic policies (Republican principles) with center-left social policies (Democratic principles). There ought to be a way to provide a kind of ethical capitalism that allows room for social welfare, that values a way of life that emphasizes personal responsibility and yet provides equal opportunity for all, that allows for private partnerships but fully invests in human development. I think something like that has been called the Third Way, but there’s never been a successful melding of the right with the left into a kind of centrism that’s been acceptable to everyone. Still, there must be a way to turn the pushing-and-shoving that we now have into something more like a well-modulated tune or an intricate but well-balanced dance. But it’s asking too much of career politicians to expect such a melding of realism and idealism to come from them. It's up to us - individually and collectively - to make it happen.

6. The idea of Jubilee, remission of debt every 7 (or 7X7) years is written in the Bible, but is an explicit example ever given? [p.73]

I don’t think that there’s ever been archeological or historical evidence showing when all leased or mortgaged lands were returned to their original owners and all slaves and bonded laborers were set free (Leviticus 25: 10, 25-28, 39-41). So, I know of no such explicit example. Such an event would quite naturally pose a problem for banking and land transactions, but special provisions did seem to exist to adjudicate those issues (Leviticus 25: 15-16). The underlying intent is much the same as it was for the law of gleaning (Leviticus 19: 9-10) – which ensured that every farmer would have access to some means of production, whether or not it came from his own farm or when he was only a laborer on somebody else’s farm.

But the fact that Leviticus 25 goes into such extraordinary detail about it, suggests to me that those laws either were followed in Israel or that they should have been implemented by at least some of the population. The whole point of these rules was that no Israelite would ever become a slave to another Israelite. The Year of the Jubilee, then, may not be just some kind of utopian literary fiction. Its widespread neglect probably came about, not because the jubilee was unfeasible, but because the wealthy (like too many today) were not willing to accept its social and economic implications – it would’ve been too costly and disruptive for them.

7. What is the time difference between Leviticus and Jesus? [p.73]

The timeframe is far too difficult to pin down, because that third book of the Torah developed over a long, long period of time – Leviticus wasn’t even recognized as a “book” at all, most scholars suggest, until sometime between 538 and 332 BCE. Before that, it was simply an evolving set of laws marking that culture’s own evolution as a people. That’s a very long stretch of history. The 30-some-odd years of Jesus were a blink-of-an-eye in comparison.

8. Do you find yourself reading the exegetical content with a more interactive approach and the archaeological content with a more one-way approach of simply soaking up the content (after looking up the terminology on Wikipedia)? [p.90]

Okay, I admit it; I am a word person. So, I find the exegetical content far more interesting and engaging than any of the archeological content. As the archeology provides insights into the lives of the people of that era, it is interesting in itself, of course. But the text – how it is worded, knowing those who created it, and how they viewed the events, life and words of Jesus from their own personal points of view – that has always been far more captivating to me.

9. Does Luke’s use of synagogue-as-building argue for a later date of authorship? [p.91]

Not necessarily. As our authors point out here, a lot of Luke’s narrative references “a viewpoint outside Palestine,” so it “shows only that he envisioned the events as occurring in an environment similar to his” – one where synagogues are usually buildings. As Crossan and Reed continue on this subject:

“But Jews in Galilean villages at the time of Jesus met in synagogues-as-

gatherings, maybe at times in an open square, a large house’s courtyard,

a village elder’s residence, and, in larger villages or towns, in modest

structures no longer identifiable as synagogues by excavators” [Ibid].

As our authors have concluded, “to speak about the ‘synagogue of Jesus’ at Capernaum has no archaeological credibility.” So, it doesn’t really lead us, then, to a conclusion that the Gospel According to Luke must have “a later date of authorship.”

10. Does the Kingdom of God more closely match the life of modern homeless than it matches those of us with (fairly) secure homes? [p.96]

I would never equate “the Kingdom of God” with the life of any homeless person – an itinerant, such as Jesus, the Buddha or Gandhi, maybe, but never someone struggling to survive while living in a cardboard box under a freeway overpass.

Week 2 Questions

1 – What does “races” refer to at the end of the Epiphanius quote? 22

2 – How do you explain Luke writing about a synagogue in 4:16-30? 27

3 – How do you decide what level of detail to use when reading the Bible? For example you might choose the “line” level when reading the Forgotten Creed in Galatians or the Book level when reading Acts as the myth of Christian foundations. 25

4 – What is meant by saying Jesus is “learned” on pg. 30?

5 – With 2 – 400 inhabitants, how many “buildings”, from shed upward, would you expect there to be in Nazareth in 25 C.E.? 32

6 – What are the approximate numerical dates for the historical Periods so far mentioned? 35

7 – Dating Documents: If Luke was written in the 80’s and Acts was written in 115 then there are 35 years between them. Is this reasonable, and if not, which number(s) would you adjust and how? 38

8 – What is a good modern example of “vituperatio”? 41

9 – What comments do you have on the divine birth of Jesus? 50

Responses to Week 2 Questions

Chapter One [continued]: “Layers upon Layers upon Layers”

1. What does “races” refer to at the end of the Epiphanius quote? [p.22]

It appears to refer to Gentiles – i.e., all of those “nations” that were not Jewish.

2. How do you explain Luke writing about a synagogue in 4:16-30? [p.27]

As our authors point out, I doubt that it referred to any structure like a building [p.26]. I think he would’ve used it in its original, or literal, sense which simply meant “a gathering” – not unlike the Lutz book group which often seems very much like a house-church to me.

3. How do you decide what level of detail to use when reading the Bible? For example you might choose the “line” level when reading the Forgotten Creed in Galatians or the Book level when reading Acts as the myth of Christian foundations. [p.25]

Having only rudimentary training in both biblical Greek (Koiné) and Hebrew, I’ve discovered that every translation is an interpretation. So, it’s critically important – as much as possible – to determine its original meaning and the author’s intention behind the use of key words and phrases. This is what exegesis is. [As I’ve mentioned to our group, more than once, an example is the English word, “heresy.” It originally meant, in Koiné Greek, “a choice,” but the Church that came to interpret the word as “a wrong belief.”] So, when it comes to reading scripture that we’ve ascribed with a level of holiness, the more attention to detail, the better.

4. What is meant by saying Jesus is “learned” on pg. 30?

The assumption has always been that he was a wise man (a “sage” as some Westar scholars have called him) – a teacher of thought-provoking parables – so in that sense, he could be considered to be well-informed and knowledgeable, learned. But I tend to agree with Crossan that it would’ve been highly unlikely for a Jewish peasant at that time, such as Jesus was, to have learned to read and write. I think that whatever learning Jesus had, he acquired by experience coupled with remarkable intelligence and charisma.

5. With 2 – 400 inhabitants, how many “buildings,” from shed upward, would you expect there to be in Nazareth in 25 C.E.? [p.32]

I have no way of knowing. Given the average home as housing no more than three residents, I’d guess that there were between 60 to 150 buildings – no more.

6. What are the approximate numerical dates for the historical Periods so far mentioned? [p.35]

If we’re talking about Nazareth at the time of Jesus, the last I heard the dates for his life were between 6 and 4 BCE, when he was born, until around 30 CE, when he died.

7. Dating Documents: If Luke was written in the 80’s and Acts was written in 115 then there are 35 years between them. Is this reasonable, and if not, which number(s) would you adjust and how? [p.38]

Most scholars believe that The Gospel According to Luke concludes where the Book of Acts begins – namely, with the Christ figure’s “Ascension” into heaven. I think it’s more reasonable to think that the author wrote both in no more than a twenty-year period (half a lifetime back in those days) between 70 and 90 CE– but it even could’ve been earlier than that.

8. What is a good modern example of “vituperatio”? [p.41]

What goes on almost daily in our own political system – both from the right and from the left – could well be labeled “character assassination, negative campaigning, and polemical advertising.” Some of it’s deserved, but much of it isn’t. While not all of it rises to the level of “libel and slander,” regrettably, much of it comes very close to that. It’s the very meaning of the word vituperation, of course, in English: “verbal abuse or castigation, violent denunciation or condemnation.” We’ve particularly been subjected to it for the last four years – but Trump’s been a master of it for many, many years before he was elected.

9. What comments do you have on the divine birth of Jesus? [p.50]

It was about as divine as the normal birth of every other human being is.

Responses to Week 1 Questions

Prologue: “Stones and Texts”

1. What are some of the things you hope to learn from studying this book? The most important one for you? [p.xvi]

I hope to learn more about the culture and social world that existed at the time of the “Jesus movement” and then gave rise to Christianity. I hope to see ways the archeological finds either support or undermine the positions of the New Testament – through Crossan’s textual exegesis and conclusions. Just how is “ground and gospel” linked? How can we expect to ever be able to “excavate” the real Jesus? In the end, I hope to learn more about the historical Jesus from this book – not the Christ figure that has been applied to Jesus and transfigured by the Church these many centuries after his life – that’s the most important one for me.

2. How do you think the time frame of archaeology compares to the time frame of exegesis? [p.xix]

As our authors point out, it would be a mistake to portray Galilee as it existed during the years after Jesus. That was a time of far greater “violent military resistance to Rome” [ibid.]. So any exegesis of the Jesus movement must have us viewing it as a time of non-violent resistance in the face of the injustice and dominance applied by Rome. That’s what it was like when Jesus lived and any biblical texts that claim to be authentic ought to reflect that reality.

Introduction: “The Top Ten Discoveries for Excavating Jesus”

3. Which of the 10 Discoveries do you think is A) most important? And B) most interesting? Why? [pp.2-5]

I would have to agree with our authors’ conclusions that #1, the Caiaphas Ossuary is the most important because (as it’s noted) it reveals “a direct link to the gospel stories of Jesus’ execution” [p.2].

And even though gruesome, I found #5, the Crucified Man, most interesting – not only because its detail appears to debunk some of the later artwork portrayals of just how Jesus must have been crucified, but because it speaks poignantly of a family who only becomes reunited after death. Curiously enough, it also tells us that our name for “John” in English is nowhere near the Hebrew and Aramaic version of “Yehochanan” – interesting.

4. Repeat for exegetical discoveries. [pp.7-10]

I find it difficult to narrow any single one of these discoveries as being the “most important” – so I’d fudge and combine #2, the Nag Hammadi Codices, with #6, the Gospel of Thomas (my personal favorite!). Nag Hammadi, for its revelation of just how widespread the extent of Gnosticism was in the first and second centuries of the Common Era, and that those codices “are extremely important as an indication...of the diversity within early Christianity itself” [p.7] – i.e., there was no such thing as orthodoxy in those decades after Jesus’ death. And, as Crossan points out, while Thomas was just one among many of the texts found at Nag Hammadi, it may very well be more of a representation of the actual sayings of Jesus than any of those that were later delineated in the traditional big four: Mark, Matthew, Luke and John – especially since the Gospel of Thomas holds none of the fictionalized accounts of Jesus’ birth, miracles, dying and resurrection that we especially find in Matthew, Luke and John.

I also renewed my interest in #8, the Didache (or “Teaching”), because I remember how fascinated I was back in seminary at Duke University to discover just how much the catechism of Christianity had evolved by the second half of the 1st century. To me, it’s further proof of the futility of claiming that there must be one (and only one) version of Christian orthodoxy. I find that the Didache is also very interesting in that it begins with the “most radical sayings” of Jesus – as if those are the ones that are most important to that early community of Jesus followers, not stories that others made up about him (e.g., birth, miracles, and resurrection narratives).

Chapter One: “Layers upon Layers upon Layers”

5. How do you think we have decreased Jesus’ Jewish identity and increased his social status? [p.15]

I assume that by the pronoun “we” you’re referring to the institutional Church – in all of its iterations. The answer is tragically simple: “we” have transformed a humble yet charismatic Jewish sage into God incarnate. The man has disappeared because “we” have erased him. Just as bad, “we” have replaced him with a mythical figure and elevated his status to the level of a magical being who no longer has any relationship whatsoever with his humble beginnings.

6. Take a look at Nazareth on Google Earth. Comments? [p.18]

The most significant impression, of course, is that the village of Nazareth – as Jesus knew it – is simply no longer there. There has been an attempt to recreate it in a museum called “Nazareth Village” that was built in 2000 – complete with houses, terraced fields, wine and olive presses. It holds reenactments for tourists of what life might have been like in Galilee at the time of Jesus. But it’s no more than a miniature terrarium tucked into a hillside while modern-day Nazareth, which surrounds it, is just as our authors have described it [pp.15-16].

7. What kind of leadership do you imagine existed during Jesus’ time in the village of Nazareth? What do you think the population might have been? [p.18]

1st century Nazareth was a peasant village in an agrarian society, so if there was any kind of “leadership” outside of the extended family, it didn’t exist in the village itself. The temple-oriented Judaism of that time meant that leadership might have been at the only temple that existed – but that was in Jerusalem. There were three small religious groups: one were the Pharisees, another were the Essenes, and an even smaller number were the Sadducees. The Essenes were a fringe group, a radical priestly sect with extremely strict rules, so I can’t see them as having much influence over a bunch of peasants in Nazareth. The more aristocratic group were the Sadducees who maintained some old-fashioned theological opinions – most notably denying resurrection, but that doctrine was accepted by most Jews of the 1st century. The Pharisees had the reputation of being the most precise interpreters of the Torah, so if there was any kind of leadership at all, they might have been the ones who provided it.

8. What would you dislike most if you were forced into the lifestyle of a Galilean peasant? [p.20]

I think that I’d dislike most my lack of independence – alongside the drudgery of hard work, day-after-day, without any prospects for it ever leading to a change toward a better life. What’s more, all of the work done by a Galilean peasant at that time really only benefitted the urban elite and wealthy landowners through burdensome tax quotas. Daily life just meant hard and unceasing labor in the fields for any Jewish peasant. As our authors point out:

“Peasants...had no cash, they had little land, they paid their taxes and

eked out a living, their bodies bore the scars of hard work, and they

were despised. This was the world of Jesus the peasant” [p.21].

If I were a 1st century Jewish peasant and didn’t have a family who depended upon me, I would be sorely tempted to run away and find some other way to live. Carpentry, now, there’s a possibility – I wonder if Joseph of Arimathea could have used another apprentice?

Week 1 Questions

1 – What are some of the things you hope to learn from studying this book? The most important one for you? xvi

2 – How do you think the time frame of archaeology compares to the time frame of exegesis? xix

3 - Which of the 10 Discoveries do you think is A) most important? And B) most interesting? Why? 5

4 – Repeat for exegetical discoveries. 10

5 – How do you think we have decreased Jesus’ Jewish identity and increased his social status? 15

6 – Take a look at Nazareth on Google Earth. Comments? 18

7 – What kind of leadership do you imagine during Jesus’ time in the village of Nazareth? What do you think the population might have been? 18

8 – What would you dislike most if you were forced into the lifestyle of a Galilean peasant? 20