This book study begins April 11, 2021 only on Zoom.

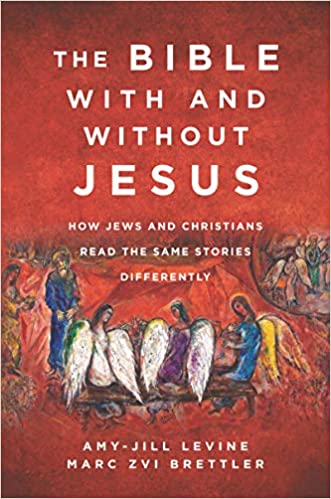

Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler aim to foster better understanding between Jews and Christians in this impeccable volume examining well-known passages from Israel’s scriptures that are important to the New Testament. Stories they examine include the creation of the world, the Garden of Eden, and Jonah’s prophetic mission. For familiar texts such as “an eye for an eye” and “the virgin shall conceive and bear a son,” the authors trace how they were interpreted at different times by ancient Israelites, New Testament authors, postbiblical Jews, and later Christians. For example, viewing Adam and Eve as misguided actors requires “a code of conduct, and so we have the Jewish Torah, which helps to harness the evil inclination”—but if the story is considered “a narrative of a fall, then we require a narrative of a redemption, and so we have the Christian story.” The effect is often one of appreciation of the influence of translation choices—for example, Isaiah refers to an “almah,” literally meaning a young woman in Hebrew, but the Septuagint, which rendered the Bible in Greek, chose to translate it as “parthenos,” a term affiliated with virgin birth. This remarkable, accessible study will appeal to anyone interested in the Hebrew Bible.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Week 12 Questions

1 – What comes to your mind when you hear the idiom “S[s]on of M[m]an”? 384 (yes, before reading the rest of the chapter)

2 – How do you think “we” got from the son of man idiom on pg. 383 meaning (possibly) a homeless person to a “technical term referring to Jesus as having divine authority.” on pg. 385?

3 – Do you know of any case where instead of “ben adam”, a phrase is used that might be translated as “daughter of humanity”? 388

4 – Is consistency and honesty an attribute of your God? 389?

5 – Comments on the last two sentences on pg. 403? (especially after reviewing the book’s publication date)

6 – Why do you think the “Son of Man” is so rare after the Gospels in the New Testament? 405

7 – Do you think it’s better to modernize the Bible with non-gender translations OR teach the gendered translation as an artifact of the time the Bible was written? (or do you have another approach to the gender issues in the Bible?) 412

8 – What are our chances of 1) receiving a new covenant, and 2) actually following it? 416

A – Have you noticed how the book of Hebrews is mentioned continually throughout our book? Perhaps we should read it?

9 – “A covenant written on our heart… requires no teachers.” Comments? 418

10 – What would be your “job description” of a Messiah? 418

11 – How comfortable are you with your own interaction with the Bible? 426

Week 11 Questions

1 – Do you like any of the reasons for Ps. 22 being chosen to articulate Jesus’ final minutes? If so, which one(s)? 351

2 – While none of us expect to be crucified, we will all dies. Is there any bible verse you think will be applicable to your death? Which one(s)? Or, if no, why not? 353

3 – You may want to read Ps. 22, 69, and 118. What is your impress of each of theses, considered from both what you think of the writer’s culture and how they may be envisioned now? 354

4 – In using things like “Where it is written…” or “Have you not read…”, it appears that literacy is assumed. Where do you think this assumption comes from? 357

5 – Compare the use of psalms and prayers of old to our modern professional services. 360

6 – What do you think has changed such that “present day worshipers might consider it impolite to issue commands to God, [but] ancient Israel did not.”? 363

7 – What do you think of the idea that the Bible grew to be more magical (aka divinely inspired) through the ages? 370

8 – Is there any particular direction(s) you see in which Biblical reference choices are made bye Jews or Christians? 374

9 – How do you see the difference between “I see this Psalm as…” vs. “This Psalm represents…” ? 377

10 – Do you trust in “God’s ultimate victory…”? Why (or not)? What do you think it will look like? 379

Week 10 Questions

A – I recommend starting this chapter by reading the very short book of Jonah.

1 – How do you understand the comparison between the “sign of Jonah” and the sign of the Son of Man? 317

2 – Jonah was a foreigner in Nineveh. Who do you think may have filled his position in our country? 317

3 – A “sign” seems to have been very important to folks in Jesus’ time/culture. What do you think has the function of a sign now? 318

4 – Do you see a connection between Jonah and Jesus sleeping during a storm at sea? 322

5 – “have self-serving prayers any value?” If so, what? 325

6 – Have you ever done something significant(ly different) when given a second chance? 326

7 – We have heard that abused children (can) become abusing adults. Does this continue “to the third and fourth generation.”? 329

8 – “once the door is open to allegorical interpretations…” Do you find yourself seeing allegory in much/some/any of what you read? 334

9 – Our authors have expanded (allegorized?) Jonah into almost all moral/ethical areas. Have you seen any of these ideas in Jonah before? 341

B – I have seen excellent pictures of the three (serial) fish swallowing Jonah on the floor of the Huqoq synagogue.

10 – If you were to use Jonah as an “open sign”, what would you fill it with? 342

11 – Jonah is often used as a children’s story. If you have any recollection thereof, were the lessons appropriate? 343

Week 9 Questions

1 – Can you recall when you first encountered the idea of the suffering servant? 289

2 – Do you think Jesus saw himself in the role of that servant? 290

3 – Can you tell, from the 1 Peter quote on pg. 292, that it is addressed to slaves?

4 – “But who is the servant?” 296

5 – In what way, if any, do you feel you are God’s servant? 298

6 – What reaction or impression did you get from “resemble the contents of a successful big-game hunt on the exegetical savannah.”? 303

7 – Does it make any difference to you that we Christians have only a single volume, the Bible, as a resource while other religions (especially Jews, in this case) have so many varying sources? 306

8 – Do you find any of the rabbinic images of a suffering messiah particularly appealing? 307

9 – How would you understand ‘God may afflict with disease anyone ”in whom the Lord delights.”’? 309

10 – What do you think about the suffering servant being absent from Jewish liturgy while it is included in the Christian lectionary? 310

11 – Any comments on the development of the suffering servant over the 2600 years covered in this chapter? 312

Responses to Week 9 Questions

Chapter 9: “Isaiah’s Suffering Servant” (pp.287-312)

“By His Bruises We Are Healed” (pp.287-294)

1. Can you recall when you first encountered the idea of the suffering servant? (p.289)

I’ve been in and part of the Church all of my life, so I really can’t recall when I “first encountered the idea of the suffering servant.” At some point – during my later childhood and teenage years – I wondered why Jesus seemed so willing to step into such a role. I couldn’t see that his suffering really accomplished that much. It just got him killed. Could he not have discovered, I thought, a more effective way of having his voice be heard?

Then I ran into this “sacrificial atonement” concept. It is an abomination.

2. Do you think Jesus saw himself in the role of that servant? (p.290)

No. I think that he was just trying to reform Judaism – to make it more compassionate, loving, just and relevant.

3. Can you tell, from the 1 Peter quote on pg. 292, that it is addressed to slaves?

No. I’ve no idea where our authors got that assumption.

“The ‘Suffering Servant’ in His Historical Context” (pp.295-303)

4. “But who is the servant?” (p.296)

As our authors finally conclude at the end of this section: “Identifying this person, and even determining whether the servant is identical in all of its uses in Isaiah 40-55, is impossible” (p.303). So, in the end, nobody really knows. On the other hand, I think that’s exactly why the early Jesus-followers stepped into the breech and put his name at the top of, not just one, but two figureheads of Judaism: this ritualized suffering servant image and the very messiah that was supposed to be Israel’s savior.

Our authors do come to the conclusion, however, that this “suffering servant” was meant to refer to an individual (p.297), but nobody on any list of Israel’s leaders throughout its history fulfilled that role. It still makes some sense to me, though, that this “servant” could be the model for an individual who exemplifies “the community of Israel” – like a national super hero who combined the best of Abraham, David, Isaiah, Joshua and Moses all rolled into one.

That this individual’s “suffering is on behalf of the gentile nations” (pp.296-297) makes no sense to me and seems like a bit of a stretch.

5. In what way, if any, do you feel you are God’s servant? (p.298)

I don’t feel at all like I’m “in service” to God – as if God were some kind of task master (as “He” so often is portrayed in the Bible) and I was “His” indentured servant. Besides, it all too often promotes the kind of slavish behavior that we often see in fundamentalism. What’s more, it further compounds the kind of anthropomorphic imagery of God that I have long rejected. If I am in service to anyone, it’s to my family, my community, and to the causes of love and justice – just not to any one person (or deity personified) in particular.

6. What reaction or impression did you get from “resemble the contents of a successful big-game hunt on the exegetical savannah.”? (p.303)

While Tryggve N.D. Mettinger (the author of that phrase) may have admired his linguistic ability to come up with such a metaphor, it seemed to me like such a strange non sequitur that I didn’t give it much thought at all.

“The Servant’s History in Later Jewish and Christian Traditions” (pp.304-312)

7. Does it make any difference to you that we Christians have only a single volume, the Bible, as a resource while other religions (especially Jews, in this case) have so many varying sources? (p.306)

Well, we do have the Westar Institute, various schools of theology, and all different kinds of scholarly-supported biblical studies (even though most of those, unfortunately, have been predominantly from decidedly traditional or orthodox perspectives). But the Bible isn’t “only a single volume.” It is, of course, at least sixty-six books (The Roman Catholic Church recognizes seventy-three.) – and only one culture’s attempt to unpack the encounters human beings believe that they’ve had with God. What’s more, some of those “books” can rightly be separated into several volumes themselves – Isaiah being the classic example. Made up of some sixty-six chapters, the “Book of Isaiah” was composed over a period of about two centuries and has been divided by scholars into at least two (sometimes three) major sections: 1st Isaiah being chapters 1-39; 2nd Isaiah (or Deutero-Isaiah) is chapters 40-55 or 40-66 – but then that’s often subdivided into 3rd Isaiah (or Trito-Isaiah) which is commonly considered to be chapters 56-66.

That being said, we Christians tend to focus far too much on only twenty-seven of those books within the Bible – the ones we’ve all come to call the New Testament – and then we’ve incorrectly assumed that the “Old” testament even predicts the “New” one! We used to have many more resources: The Gospel of the Ebionites, The Gospel of the Nazarenes, The Gospel of Philip, The Gospel of Truth, The Gospel of the Savior, The Infancy Gospel of Thomas as well as The Infancy Gospel of James, The Gospel of Peter, The Gospel of Thomas, The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, and even The Gospel of Judas. And all of these are just the so-called “Gospel” stories (There’s the theory of the Q Gospel, as well – but that’s another story in itself.)! We also have the Apocalypse of Peter, The Epistle of Barnabas, the Shepherd of Hermas, 1st Clement, The Didache, the Lost Epistle to the Corinthians, and even the Third Letter to the Corinthians.

But somebody, way-back-when, finally said, “Hold it! Stop! This is too much! Let’s get our heads together and pare it down.” Constantine’s sword began the really serious first cutting; and we’ve suffered the restrictions put upon us by orthodoxy and tradition ever since.

8. Do you find any of the rabbinic images of a suffering messiah particularly appealing? (p.307)

I don’t think that I would ever find such an image “appealing.” However, there is some merit in the interpretation that “the passage can be read as saying that the messiah may be found among those who suffer” (ibid.). For far too long, humanity has ignored those people – the unjust suffering of the many under the rule of the few whose power only came from their wealth and positions of privilege. That a wise and charismatic itinerant rabbi from Nazareth would come along and be able to point that out to us, and call us to change our ways, was a good thing. Tragically, however, history has failed to lead us into fully embracing that life-giving way – whether Jesus came to be our guiding light, or we rested our hopes and belief in Muhammad, the Buddha, Mahatma Gandhi, or The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. So, the suffering has continued unabated.

9. How would you understand “God may afflict with disease anyone ”in whom the Lord delights.”’? (p.309)

It makes about as much sense as making a sacrifice of your “only Son” so that a “Father God” would forgive the rest of us of our sin. It’s a sick and twisted view of life.

10. What do you think about the suffering servant being absent from Jewish liturgy while it is included in the Christian lectionary? (p.310)

It’s just one more example of proof-texting scripture – or eisegesis – where a small group of “church fathers” long ago selected certain images that seemed to affirm their own preconceived notions about the image, nature and work of God. Tragically, that human capacity for self-delusion continues unrestrained.

11. Any comments on the development of the suffering servant over the 2600 years covered in this chapter? (p.312)

Give the man a rest, shall we? And, significantly, that model has almost always been a male when, in fact, women have endured just as much or more suffering than men – and for far too long. Besides, that “the community needed to find new ways to feel that it was deserving of forgiveness” and found that “the suffering servant...fills this need” (p.302) is just sick.

For God’s sake – if not for our own – stop it! Let’s embrace any one of the many biblical models that makes more sense. If our choices were restricted to just the Hebrew scriptures, these are two of my favorites:

“Look how both the heavens and the earth are witnesses against

you that, all around you, you have life and death, blessings and

curses. Now choose life, finally, so that you and your children

may live.” – Deuteronomy 30: 19 (my translation)

“God has shown you, people, what is good. What is required of

you is to act with justice, to love kindness, and to walk with all

humility alongside your image of God.” – Micah 6: 8 (my translation)

What’s your own favorite passage of scripture – and why?

Week 8 Questions

1 – Do you like any of the alternatives mentioned on pg. 260?

2 – What do you think about asking God for a “sign”? 263

3 – Why do you think ‘hineh’ is translated as ‘look!’? 265

4 – I would like to ask a question about the last sentence on pg. 274, but don't know how

to phrase one that would be interesting and thought provoking. Can you help?

5 – “Isaiah 7:14 is a fundamental dividing point between Jews and Christians…”. What do

you think? 277

6 – Does the Jewish description of Isaiah 7:14 change your understanding of this dividing

point? 279

7 – Are our authors inconsistent when contrasting ‘almah vs parthenos on pg. 280 after

their previous (pg. 271) “But not every parthenos is a virgin…”?

8 – Does the “theological accommodation” referred to on pg. 282 mean that we are free to

interpret the Bible in any way we wish?

9 – What is one difference you see in the interpretation of Mary as a virgin vs. NOT a

virgin? 282

10 – What is one idea mentioned “time an time again” that has become less important? 283

Responses to Week 8 Questions

Chapter 8: “A Virgin Will Conceive and Bear a Child” (pp.257-283)

“To Fulfill What Had Been Spoken” (pp.257-260)

1. Do you like any of the alternatives mentioned on pg. 260?

In the end, I think that the last one simply makes the most sense: “Historians cannot determine all the details of Jesus’s conception and birth.” But, if I had to choose from any of the others, I’d go with the very believable suggestion “that Joseph was the father, and the account of a virginal conception developed in competition with stories of Greek and Roman gods fathering children....” The authors of the Gospels thought that it was critical to not just add Jesus to that divine panoply, but to put him at the top – above and beyond all others.

“Isaiah in His Context” (pp.261-270)

2. What do you think about asking God for a “sign”? (p.263)

My concept of God doesn’t involve the presence of a supernatural being who responds in such a way. As our authors rightly note, here, “not all signs indicate miracles.” There are “signs and wonders” throughout the entire universe, however, that I claim are evidence of the presence of God. The list is long and truly wondrous.

3. Why do you think ‘hineh’ is translated as ‘look!’? (p.265)

The translators wanted to claim that you could actually “see” something. “Behold,” on the other hand, only invites us to “pay attention” to what’s going on in front of us – or all around us. It “functions as an attention-getter” (p.266). As our authors point out there at the bottom of p. 265, “etymologically the Hebrew term has nothing to do with seeing.” If we would pay attention, we could “behold” divine blessings everywhere.

“From ‘Young Woman” to ‘Virgin’” (pp.271-274)

4. Consider the last sentence on pg.274:

“The issue is not one of right reading versus wrong reading; rather,

if one begins with the premise that the Christ is predicted by and

present in what becomes called the ‘Old Testament’ one will find

him there.”

Do you think that the whole story of Jesus as the Christ (the “Anointed One” of Israel) became a self-fulfilling prophecy because the authors of that story simply wanted to read the Hebrew scriptures that way – in a very real sense, then, they made it all up? What makes you come to your conclusion – one way or the other?

In short, the authors of the New Testament only “found” that these passages from the Hebrew scriptures predicted one Jesus of Nazareth to be the long-awaited Christ/Messiah, because they wanted them to point that way. They expounded on the concept and claimed that Jesus fulfilled all of them. So, yes, either they made it all up because they really wanted it to be true, or they were just speaking metaphorically in opposition to the only “divine beings” that their lives were presented with: the emperors of Rome.

“From Prediction to Polemic” (pp.275-283)

5. “Isaiah 7:14 is a fundamental dividing point between Jews and Christians....” What do you think? (p.277)

Yes, it clearly is a “fundamental dividing point” between us. Either Jesus of Nazareth completely fulfilled the Jewish expectations of a Messiah, or he didn’t. For the Jews, he didn’t. For Christians, he did. That has made for a profoundly different understanding of the life of Jesus. On the one hand he was – at most – a charismatic sage and Jewish prophet. On the other hand he was the very instrument (“Son”) of God uniquely bringing the offering of salvation to all who would believe in his status as the Anointed One, the Messiah/Christ.

6. Does the Jewish description of Isaiah 7:14 change your understanding of this dividing point? (p.279)

It did – back when I discovered it while I was in seminary in the late 1970s and studying biblical Hebrew. It absolutely was a dividing point for me and yet only confirmed what I’d long suspected about the mythic claim of Christianity – that Jesus was the one and only Son of God. That became a myth because it was first perpetuated by the early Church, but then has been claimed as “the Gospel Truth” ever since.

7. Are our authors inconsistent when contrasting ‘almah vs parthenos on pg. 280 after their previous (pg. 271) “But not every parthenos is a virgin…”?

I think it’s more a matter of the translators of the Septuagint who chose to equate the Hebrew word for “young woman” with a sexual “virgin.” Our authors try to equate it with the English word “maid” – that a maid was “a woman with a ‘maidenhead,’ that is, a hymen” and that “bridesmaids were supposed to be virgins....” It was a very unfortunate translation that has completely replaced one with the other and so become pivotal in how Christianity has come to understand Mary, the mother of Jesus. She was then seen as more than just “a young woman of marriageable age.” She was one who had become magically pregnant without any sexual intercourse whatsoever.

8. Does the “theological accommodation” referred to on pg. 282 mean that we are free to interpret the Bible in any way we wish?

In a word, no. That hasn’t stopped theologians, from the very beginning however, to assume conclusions that the text never meant. It’s called eisegesis: an interpretation that expresses the interpreter’s own ideas or bias instead of the actual meaning of the text. While such interpreters may not have meant to lead us astray, it has. [NOTE: the etymology of that very word, eisḗgesis, in the Greek, means to “lead” someone “into” a certain conclusion.]

As our authors pointed out earlier:

“By the time the author of Matthew was writing circa 90 CE, more

than seven centuries after the time of Isaiah, Isaiah 7:14 had become

reinterpreted and recontextualized” (p.281)

So, I find it very interesting that our authors should, themselves, conclude this:

“Like almost all biblical texts, Isaiah’s prophecy opens to multiple

interpretations, and we would do well to realize how different

readings, translations, and historical contexts have led to these

differences, and to appreciate that our personal preferences

should not determine how others, from different religious

communities, must read the text” (pp.282-283).

You’d never get an ultra-orthodox theologian or biblical fundamentalist to admit that such a thing is possible. But, once again, I’m reminded of what my professor of Koine Greek at Duke University, Dr. Mickey Efird, would always say to us: “Every translation is an interpretation.”

9. What is one difference you see in the interpretation of Mary as a virgin vs. NOT a virgin? (p.282)

She certainly could not have been both – either she was a young woman who had experienced sexual intercourse or she hadn’t. Unfortunately (for the rest of us Methodists!), it was “Methodist scholar Ben Witherington” who unequivocally concluded here “that God would contravene the laws of nature and so create not simply a ‘sign’ but a miracle is historical fact.” That is exactly the kind of “blind faith” that, regrettably, continues to be emphasized today (cf. p.283) – among most fundamentalists, but particularly within Christianity. In the case of “the interpretation of Mary as a virgin,” it’s changed a common human pregnancy into an incredible supernatural event. In the end – at least for me – that conclusion is simply unbelievable.

10. What is one idea mentioned “time and time again” that has become less important? (p.283)

I don’t think it’s just our Lutz Book Group that has moved away from biblical references that, “time and time again,” speak of supernatural events as if they actually happened that way. Thankfully, many others have rejected such literalism as well. Still others have begun to see the wisdom in something John Dominic Crossan once famously said:

“My point, once again, is not that those ancient people told literal

stories and we are now smart enough to take them symbolically,

but that they told them symbolically and we are now dumb

enough to take them literally.”

As Art Dewey has appropriately pointed out in his opening Editorial in the most recent issue of Westar’s publication, The Fourth R (May-June 2021), “the traditional narrative of the development of Christianity does not fit the evidence” (p.2). The Bible is decidedly not the literal Word of God. So, we have every right to question its conclusions. That we have not, remains to be a tragedy that is compounded every single Sunday morning in the majority of churches across the entire world.

Week 7 Questions

1 – If, as the Jesus Seminar voted, Jesus didn’t say these things about his flesh and blood, where did they come from and to what do the metaphors applied by the gospel writers refer? 221

2 – What do you think of Philo’s Passover interpretation? 225

3 – If we don’t view God as an “old man in the sky,” what is actually happening (in a 21st century view) when blood sacrifices are made? 230

4 - “…the divine presence...likes to live in a low-sin environment” Comments? 232

5 – As blood of the lam was apotropaic in ancient Egypt, what performs that function now? 237

6 – “in order that I might horrify them, so they might know that I am the LORD.” Comments? 240

7 – What do you think of the idea that sh-u-v is a later development that replaced blood? 244

8 – The destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem changed Judaism greatly. Do we have a similar change in Christianity? 246

9 – What can an eight day old child atone for? 250

10 – How did your understanding of sacrifice and atonement change while reading this chapter?

Responses to Week 7 Questions

Chapter 7: “’Drink My Blood’”: Sacrifice and Atonement” (pp.221-253)

Let me repeat, at the outset, some of what I said in my response to question #2 from Chapter 5 and its discussion of supersessionism: I have always rejected the Church’s claim that “atonement” meant “reparation for a wrong or sin” – i.e., the doctrine that claimed that the way God reconciled “Himself” with humanity was through the life, suffering, and death of “His” son, Jesus, as the Jewish Christ figure. That always sounded a lot like divine child abuse to me.

So, again, I’d like to regain the etymological meaning of the word “atonement” which originally meant to make “at one” or put “in harmony” those who have become estranged from one another. Even as this term moved from Medieval Latin into Middle English “onement” meant “unifying” what had been separated. So, let’s finally get rid of this archaic and horrific concept of human sacrifice as the only way that this reunification is accomplished.

Jesus was executed as a common criminal by Rome. It was not part of any great larger plan created by God. He did not die for our sins; he died because of them.

“The Sacrificial Lamb” (pp.221-226)

1. If, as the Jesus Seminar voted, Jesus didn’t say these things about his flesh and blood, where did they come from and to what do the metaphors applied by the gospel writers refer? (p.221)

All of this just was, regrettably, part of the culture of the Ancient Near East (ANE) – and had been for centuries. As our authors point out:

“The world of Jesus and his earliest followers was a world in which

sacrifice was religious currency; everyone knew of it and everyone

recognized its value. ... It would have been very strange had Jesus’s

followers, in light of the cross, not developed the category of sacrifice”

(p.223).

“Jesus thus becomes the new ‘Passover,” whose blood will protect

his followers from (eternal) death” (p.224).

It’s truly unfortunate that we’ve perpetuated that point of view on into the 21st century.

2. What do you think of Philo’s Passover interpretation? (p.225)

I assume that you mean this quote:

“The Passover is when the soul is anxious to unlearn its subjection

to the irrational passions, and willingly submits itself to a

reasonable mastery over them” (Heir 192).

It’s not a bad idea, actually. Psychologically, it makes sense. At any number of points in our lives we might need some additional help (e.g., from a priest or counselor – and not just on a holy day through some kind of liturgy). And however you might understand Philo’s use of the word “soul” here (if you like, substitute the “mind” or our “will” at wanting to do the right thing), we often need to be reminded that we should take better control over our own lives.

“Sacrifices in Ancient Israel” (pp.227-235)

3. If we don’t view God as an “old man in the sky,” what is actually happening (in a 21st century view) when blood sacrifices are made? (p.230)

It’s about as much as what happens when hands are moved over an Ouija board. But this “burnt offering” idea has been perpetuated in the Christian liturgy of Holy Communion. As our authors point out, it was thought that such an offering “is fully consumed by God (Lev 1), and the well-being offering...is shared between the offerer and God.... This sharing indicates human-divine communion” (p.228). Really? Is this union, then, not available without it?

In the end it’s just superstitious – and dangerous – nonsense. We’re not consuming any of Jesus’s blood during Holy Communion – real or symbolic. The fact that so many people still believe in such a thing is unfortunate – to say the least.

4. “…the divine presence...likes to live in a low-sin environment” Comments? (p.232)

Wouldn’t we all? This – yet another, anthropomorphism of the divine – may or may not be just Jacob Milgrom’s opinion here; it may be one or both of our authors’. Either way, it’s a bit bizarre – and, to my mind, unbelievable. Does anyone really still take this literally?

“Passover” (pp.236-237)

5. As blood of the “l am” was apotropaic in ancient Egypt, what performs that function now? (p.237)

I’d say members of the medical community do (i.e., doctors, nurses, EMTs, etc.), as well as fire fighters, law enforcement, and – when they have to – sometimes members of the military. Their job, first and foremost, should be “to protect and serve” others. They might accidentally bleed, themselves, from wounds inflicted performing that function, but such a sacrifice is certainly not a requirement. It is their work that “protects rather than atones” (ibid).

“Human Sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible” (pp.238-240)

6. “...in order that I might horrify them, so they might know that I am the LORD.” Comments? (p.240)

Unfortunately, you just can’t “scare the Hell out of people” – well enough or that often enough – to make it work. For far too long we’ve tried doing it that way. What’s almost as bad, to my mind, it makes a horror out of God – and often the Church itself.

“Nonsacrificial Atonement” (pp.241-244)

7. What do you think of the idea that sh-u-v is a later development that replaced blood? (pp.242-243)

I like to think that the powers-that-be finally came to recognize just how barbaric and completely dysfunctional the former theory actually was. True repentance was much better than simply going through the motions of making a blood sacrifice. But I’m not sure that, in fact, was the reason that they changed their minds – it could’ve been that the whole sacrificial system just became too expensive and far too corrupt to be allowed to continue.

“Sacrifice in Postbiblical Judaism” (pp.245-247)

8. The destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem changed Judaism greatly. Do we have a similar change in Christianity? (p.246)

How about this: You don’t need Jesus or the Church to be saved from your sinful nature. Either one might help you along the way; and it apparently does work for some people. So, Christianity has made a positive difference in people’s lives – it has for me. But, all too often, it becomes frozen in mean-spirited fundamentalism. So, you have to start all over again. As our authors note, even rabbinic tradition finally came to stress “the efficacy of teshuvah in the sense of internal contrition and repentance” (p.246). So should we.

“The Blood of Circumcision” (pp.248-251)

9. What can an eight-day-old child atone for? (p.250)

I think that the tongue-in-cheek nature of your question speaks for itself. The answer? Nothing. That “the blood of circumcision is life-giving” (p.249) makes about as much sense as claiming that the practice of female genital mutilation protects the chastity and purity of young girls.

“The Blood of the Covenant” (pp.252-253)

10. How did your understanding of sacrifice and atonement change while reading this chapter?

It did not change at all. I’ve thought such concepts were wrong for as long as I began worrying over and pondering them during my childhood. It made no sense to me at all then; and it still doesn’t. That Jesus willingly went to his death was an awesome act of love. But he didn’t have to do it – for God, for me, or for anybody else. Collectively, the fact that humanity didn’t learn that lesson, just led to other deaths of such martyrs during the 1st century: people like John the Baptist, Stephen, James (the brother of Jesus), Simon Peter, Paul the Apostle, Perpetua, Felicity, Euphemia and on and on through Justin Martyr, himself, as well as, centuries later, Mahatma Gandhi, Bishop Oscar Romero, and The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. There have been literally countless such sacrifices of men and women throughout history who died simply because of their actions in the face of evil and injustice.

When will we ever learn? That question first poignantly posed by Pete Seeger – in his 1955 song “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” – and time after time afterward, still hasn’t helped us answer why we haven’t.

Week 4 Comments

2 – How can we begin to move from mythic stories about how life is toward stories of how life should be? 105

3 – “God intended ha’adam to live forever.” Where would such an idea come from? 109

4 – How much of the equality of ha’adam’s helper do you attribute to the modern worldview of our authors considering the opening section all about hierarchy? 109

5 – If you were choosing an animal to entice Eve, which would you choose rather than a snake, and why? 113

6 – Do you recall an incident of moral awakening that you would like to share? OR do you have one that you would NOT like to share? (if the latter only, a simple Yes or No will suffice.) 113

7 – What do you think of “he sacrificed his immortality for her sake.”? 114

8 – Is there anything in our modern world that corresponds to ancient curses, especially curses from / by God? 116

9 – Is punishment the best response to sin, and if not, what is better? 122

10 - How would you describe the relationship between sexuality and morality? 128

11 – Is the primary difference between Jews and Christians that Jews have questions and Christians have answers? If not, then what? 134

Week 5/6 Questions

A – What should be the function of a priest? 140

1 – Does anyone have as much trouble with Biblical pronouns as I do? I can rarely tell what he/him (almost always male!) refers to. 155

2 – Is there ever a case where supersession is a good idea?

3 – Do you agree with pg. 161, “So far, we have ..confusion…”?

4 – How do you understand “...until all is accomplished”? 183

5 – I am assuming that our group does not condone capital punishment. So what/how was our society changed so that we no longer condone capital punishment? 187

6 – What modern idea corresponds to “make a fence for the Torah”? 188

7 – What is the implication of: “They drop no stones; they were not carrying any.”? 190

8 – Weigh the value of women deriving from their ability to produce children (and thus heirs) vs the danger of death in childbirth. 195

9 – Reconcile “.., Do not swear at all, …” with being required to take an oath when being “sworn in” as a juror. 196

10 – Consider levels of “enemy”. What actions are appropriate? 200

11 - Why is escalation of conflict so common? 203

12 – What is a modern example of a difference between a real and an ideal law? 208

Responses to Week 5/6 Questions

Chapter 5: “You Are a Priest Forever” (pp.135-177)

A. What should be the function of a priest? (p.140)

Well, it’s certainly not as our authors’ take on the Book of Hebrews seems to claim: that Jesus’s “single sacrifice, of his own flesh and blood, is then sufficient to create atonement for all” and, in some miraculous way, “the Christ replaces the Torah” and that “Jesus’s sacrifice is, after the cessation of Temple sacrifice, the only means to obtain forgiveness” (p.146). That his sacrificial death “cleanses from sin any who follow him” has always seemed an abomination to me – and nothing at all like what the function of a priest ought to be.

When it comes to interpreting either the Torah or the New Testament, however, later in this chapter our authors do make an excellent point: “It may be that theologians and ethicists, rather than biblical scholars, are the ones to determine what an ‘acceptable’ reading will be” (p.172). Over the centuries, then, the function of a priest has evolved – considerably.

Consider its function within the United Methodist Church. Historically, it’s designation – at most – was only meant to be a third aspect of our ordination. A minister serving The United Methodist Church was/is ordained to provide at least these three key functions:

Priest: as pastor, the one who presides over and delivers all of the sacred rites of the Church – such as (but not limited to):

· delivering/preaching “the Word of God”

· performing baptisms

· presiding over prayers, Holy Communion, and marriages

· offering compassion and care for the sick and dying

· presiding at funerals and memorial services

· providing compassionate counseling and spiritual direction

Prophet: as advisor, the one given the authority to “order the life of the Church” for service in and to the world – as he/she perceives what the greatest needs of their community and the larger world are

Regent (King/Queen) – as the administrator (yes, in connection to the historic “divine right” of such rulers) who, in much the same way as the historic captain of the “Ship of State,” – while never actually putting his/her hands upon the wheel to steer that ship – would “plot and set the course” and then simply say to the helmsman, “Make it so.” And it would be so as the ship, then, would move in the given direction and at the speed as both had been set by the captain.

The actual words of ordination for us as pastors were delivered by our bishop as he/she laid his/her hand upon our head and intoned these solemn words:

“[Full Name], take authority as an elder

• to preach the Word of God,

• to administer the Holy Sacraments

• and to order the life of the Church;

• in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

To this day, I remember just how moved and overwhelmed I was by that moment in my own life. I am humbled to be constantly reminded of that expectation and of my limited capacity to fulfill what I have been ordained to do and be.

Which (if any) of these functions do you think were exemplified by the life and ministry of Jesus? In what ways did he do so? Which (if any) of these functions would you value most in someone who is called to be your pastor? Why? As a lay person, where would you want to add your voice in this mix so that your pastor (or the bishop who appointed him/her) doesn’t have the sole authority over all of it?

To my mind, those are very good questions to ask and have answered – in any church whose members expect their pastor to be, among other things, a priest who has been called upon to speak and act on behalf of Jesus.

Psalm 110: “An Enigmatic Royal Psalm” (pp.154-164)

1. Does anyone have as much trouble with Biblical pronouns as I do? I can rarely tell what he/him (almost always male!) refers to. (p.155)

• ‘adoni = “lord,” “master,” “sir” is simply the transliteration from Hebrew

• kyrios = just the Greek transliteration of the same word

That the word came to refer to “God,” as well, just indicates how we’ve anthropomorphized the being of God – i.e., we were, in fact, not “made in the image and likeness of God.” It was the other way around. We made God in our own image – in the images of all of the lords and masters that we knew who, somehow, ruled over our lives. And, yes, regrettably, at the time that our Bible was created, most – if not all – of these lords and masters were male. And Jesus suffered the same fate – i.e., as our authors point out in unpacking Acts 2: 34-35, “Jesus sits enthroned in the heavens” so, now, not only as regent (a “righteous king” like Melchizedek), but as ruler over the entire cosmos – as God himself (p.156).

2. Is there ever a case where supersession is a good idea?

It’s never a good idea to replace one institution with another in this way. As our authors rightly point out, you end up replacing an entire race of people with another (p.176) – and that is called genocide.

I agree with our authors when they suggest: “One way forward would be to respect the distinct claims each tradition makes regarding atonement” (ibid.). And I’ve always rejected the Church’s claim that “atonement” meant “reparation for a wrong or sin” – i.e., the doctrine claiming that the way that God reconciled “Himself” with humanity was through the life, suffering, and death of Jesus as the Christ. I’d like to regain the etymological meaning of that word: to make “at one” or “in harmony” those who’ve been separated – even as this term moved from Medieval Latin into Middle English “onement” meant “unity.”

So, let’s get rid of supersessionism once and for all, for God’s sake.

3. Do you agree with pg. 161, “So far, we have had textual confusion (Ps. 110:3) and theological confusion (110:4a)”?

Yes. At the very least, let’s agree with our authors, here at the close of this chapter, when they say, “Jews and Christians both participate in unfinished systems. ... There is little reason to claim which system ‘replaces’ the other or which is the ‘better’ path” (p.177). So, let’s keep at until we do get it right – and both science and progressive theology have major roles to play in this endeavor. We should make an effort toward some kind of resolution, but also assume the responsibility that, most likely, we will never reach a final answer that will be acceptable to everyone and for all time.

Chapter 6: “An Eye for an Eye” and “Turn the Other Cheek” (pp.179-217)

“Antithesis or Extensions?” (pp.181-185)

4. How do you understand “...until all is accomplished”? (p.183)

I was taught that it’s just as our authors explain Matthew 5: 17-18.

“Jesus proclaims that the Torah and the Prophets, and the practices

they teach, will remain for at least the lifetime of anyone hearing his

words ... ‘To fulfill’ here means ‘to complete’ in the sense of drawing

out the full implications of the Torah and the Prophets. ... According

to Matthew, Jesus – not just by his teachings but also by his life –

shows the complete meaning of Israel’s scriptures. ... Despite the

popular view that Jesus cares primarily about what one believes,

Matthew’s Gospel focuses rather on how one acts, on what one does”

(pp.183-184).

What’s more, I don’t think Jesus ever believed that he, himself, was the final culmination of that struggle – that he somehow “accomplished” what none of us could or ever can. We have our own roles to play in this vocation of learning how to be a fully human being. And following in his footsteps remains to be a good place for us to begin. WWJD, indeed.

“But I Say to You...” (pp.186-200)

5. I am assuming that our group does not condone capital punishment. So what/how was our society changed so that we no longer condone capital punishment? (p.187)

We’ve finally come to realize that it just doesn’t make good sense to kill a human being who has killed another human being – whether we believe that we’re doing so either legally or justifiably (as in mortal combat). Fundamentally, then, I think most of us have learned that retributive justice doesn’t work. Restorative justice does. We just haven’t found the will or all of the ways to make it happen.

6. What modern idea corresponds to “make a fence for the Torah”? (p.188)

Referring to the question about capital punishment, above, I think the first thing that we need to do is we have to “put a fence around” our own “righteous anger.” That attitude only has led us to seek revenge – and vengeance is not justice.

7. What is the implication of: “They drop no stones; they were not carrying any.”? (p.190)

It’s a nice metaphorical turn of a phrase by one of our authors here. In effect, whatever weapons that they thought they had in their hands in trying to trap Jesus, didn’t work at all. So, in the end, they were left “empty-handed.” Deftly done.

8. Weigh the value of women deriving from their ability to produce children (and thus heirs) vs the danger of death in childbirth. (p.195)

Backing up a bit, I do find it curious that our authors’ interpretation of Luke 18: 29-30 here concludes this way:

“In Jesus’s mission, there is no divorce, but there is also no procreation,

for creating heirs to inherit property, nor cohabitation. This is because

the end of time as we know it is soon approaching.”

Really? Our authors seem to buy into the early Christian apocalypticism that Jesus’s life marks the end of everything as we’ve known it. But it didn’t happen.

As far as the above question is concerned, to my mind, “the value of women” far exceeds just their “ability to produce children” – never mind “the danger of death in childbirth.” So, I think that the two choices compared within this question makes it a bit of a non sequitur.

9. Reconcile “.., Do not swear at all, …” with being required to take an oath when being “sworn in” as a juror. (p.196)

The injunction isn’t about never swearing at all; the heart of the issue that Jesus seems to be addressing is that one should never “’swear falsely, but carry out the vows you have made to the Lord’” (p.195). In that, he seems to be agreeing with our authors conclusion that “Deuteronomy suggests avoiding the risk” of making any vow “in the name of God.” In the end, as they observe, “Jesus mandates honesty at all times” – that all of the promises that we make absolutely must “be kept” (p.197).

So, if you take this literally, it might sound as if you should never claim that God has our back – no matter what kind of an oath we take. If your image of God is as judge, jury and executioner – the final arbiter of everything that is – then maybe you should be careful and claim a religious exemption from ever serving as a juror.

But that’s not my image of God.

10. Consider levels of “enemy.” What actions are appropriate? (p.200)

If we’re to take Jesus literally (and I’m not suggesting that we shouldn’t), there are no “levels of ‘enemy.’” You love all of them back into being a part of your life. This is what led to the category of any Christian who claimed to be a Conscientious Objector within the military. You could be awarded an exemption from ever serving in the military at all – or at least from having to carry a weapon in combat – because your faith absolutely required that you never kill another human being for any reason at all.

I could never take such an oath. Personally, and as an officer in the Marine Corps, I concluded that there were, in fact, some enemies of ours that would be better off dead – whether I found myself in the position of doing the killing or sanctioned others to do so. Does that mean that I really shouldn’t be able to consider myself a Christian?

You tell me.

“On an Eye for an Eye” (pp.201-205)

11. Why is escalation of conflict so common? (p.203)

I think the issue must go back to the depth of feeling of the combatants. If they feel like their side is the best side, the “righteous” side, or the only one worth fighting for, then conflict will continue until their side prevails. It’s so common because, regrettably, it’s so human.

“The Hebrew Bible’s Context” (pp.206-211)

12. What is a modern example of a difference between a real and an ideal law? (p.208)

Every codified law (at least in our country) was originally meant to provide equal justice to all who might break it. Tragically, however, far too many of our laws remain “ideal” and not “real.” Those with wealth and privilege (e.g. being white and not a person of color), all too often, are treated differently by law enforcement by virtue of that status. The DWB “crime” (of simply Driving While Black), for example, has often not only led to harassment, receiving a ticket, imprisonment (or worse), for blacks, but those of us with privilege who are caught violating any law while driving, are frequently just “let off with a warning.” That is ideal law made unreal.

Near the end of this chapter of our text is this quote: “When we put Jesus into his Jewish tradition, we see that both concerns, justice and mercy, remain” (p.217). Would that it were so in our own time and within our own culture.

Responses to Week 4 Questions

Chapter 4: “Adam and Eve” (pp.99-134)

“Death, Domination, and Divorce” (pp.101-104)

“The Garden of Eden” (pp.105-111)

1. Why do we hear so much about “the good old days” when we know they were actually no better? (p.105)

When it comes to the doctrine of original sin, I think we’re better off to leave that one far behind (pp.101-102). It’s definitely not part of “the good old days.” Likewise, here as it’s unpacked in this chapter, the myth of the garden of Eden is a less than adequate tale of how “to explain why life is the way it is” – it does not “explain how life should be” (p.105). It’s just a fanciful tale from within one culture as it pondered how life might have begun for them.

When it comes to matters of health and longevity, however, we are much better off than the people of ancient history – or even within the history of our own lifetimes. The “good old days” were much more plagued by illnesses and early deaths – in spite of what we might think of at the moment as we remain under the pall of this COVID-19 pandemic.

I think we hear so much about “the good old days” simply because older people don’t deal very well with many of the significant changes that are at the heart of modernity. One example might be the ways in which we interact with the internet. While it has freed up our access to information, it has dramatically reduced the person-to-person customer services that once were offered by organizations and corporations that we depend upon. A live and helpful person used to be only a phone call away. Now, however, we’re reduced to automated “chat” lines for assistance – but then they’re only programmed for specific and, so, limited questions. All too often, they just lead to communication stalemates, or we find ourselves being sent down digital “rabbit holes” which end in a complete lack of service. Was the care really better in “the good old days?” Was it true that we could get the help that we needed from another person without constantly being misdirected and sidetracked by a computer-operated system? Maybe, yes, “the good old days” did have something better to offer us.

2. How can we begin to move from mythic stories about how life is toward stories of how life should be? (p.105)

To begin with we must all be carefully taught to understand the difference between myth and reality – just as we should understand the difference between fiction and nonfiction, opinion and fact, truth and dishonesty.

We can, however, learn from the disciplines of science, sociology, psychology, philosophy, theology – and even, I submit, from myth itself – about just how it is that we ought to live our lives in health and safety. Each has a place in meeting our need to know. Each, in its own way, can help us answer many questions that have plagued humanity for a long time: How can we learn to love and not hate? What helps us eradicate disease and what can we do to bring an end to unnatural, premature death? How can we better our environment on behalf of all life? How can everyone be fed while far too many, now, are being starved to death? What makes for a well-ordered society and how can we deal with the kinds of forces that continue to undermine society and the well-being of its citizenry? What can we do to create more justice as far too many struggle with injustice? For every such question, we must find answers – and we can. But, do we have the will to, finally, create life as it should be? It’s up to us.

3. “God intended ha’adam to live forever.” Where would such an idea come from? (p.109)

As our authors first say, here, “Whether God intended for humanity to be immortal is never explicitly stated.” But the so-called “tree of life” could refer to that; but it, just as well, could refer to our desire to have complete control over our lives, to do as we please and not as God has willed that we should do and be, to make ourselves the center of the Universe – which is the place meant only for God. To want to have it all, instead, has led to the death of us.

It should be pointed out that most of the stories in Genesis – as well as elsewhere in the Bible – were actually created to answer questions that human beings have asked themselves from the very beginning: Who am I? Why am I here? Who are these others here with me? How did we get here? Who made us as we are? Why are some of us men and others women? What’s the difference between us – and how, on earth, did that happen? Do we have anything at all in common? Why is childbirth so painful? Why do we die – and so soon? Why are we different from the animals? Who or what was here before us? Why is there so much suffering? What makes someone our enemy while another is our friend? What happens to us after our death? Who is God, really? ...and on and on, questions like these have arisen about the world and our place in it. Stories, like those in the Bible, were just created to try to answer them to our satisfaction. Some have worked; others haven’t. But they’re just stories. We need to constantly remind ourselves – and others – of that fact.

4. How much of the equality of ha’adam’s helper do you attribute to the modern worldview of our authors considering the opening section all about hierarchy? (p.109)

It does seem a bit of a stretch – given the anthropocentric culture that dominated ancient Judaism which was always putting a masculine point of view at the center of their worldview – that our authors would speculate here that this “helper” doesn’t really “imply subordination (but) may be used of an equal or even someone superior” or, as they say later, that “For the Bible, what is done last, not first, can be more important” (p.110). Maybe. Maybe not. Right or wrong, I do hear the strong feminist voice of Amy-Jill Levine in this.

“Eating Forbidden Fruit” (pp.112-118)

5. If you were choosing an animal to entice Eve, which would you choose rather than a snake, and why? (p.113)

I’d choose a smooth-talking, slowly-slinking, muscular male Bengal tiger with a deep voice, penetrating eyes, and yet a softly-rumbling and seductive purr. Why? Because wild tigers are absolutely beautiful animals while, at the same time, very scary. Eve would be both terrified and mesmerized in the presence of such power.

However, this tiger would definitely have to be real in every other sense and not like some cartoon character patterned on the main antagonist and tiger, Shere Khan, from Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book.

6. Do you recall an incident of moral awakening that you would like to share OR do you have one that you would NOT like to share? (if the latter only, a simple Yes or No will suffice.) (p.113)

While rooming with a fellow-member of our university’s track team for an away meet, I learned from him just what it meant to be pulled over by the police while driving a car – not for a DUI, but for a DWB – “Driving While Black.” Charlie Craig, you see – this world-class triple-jumper on our team and friend of mine – was a black man and this had happened to him more than once. I was also stunned to hear just how often this happened to almost all black men. They were seen as being in the “wrong” neighborhood, perceived to be driving the “wrong” car, were seen as out “too late at night” or too early in the morning, but rarely ever for actually violating any of the DMV’s rules of the road.

It’s called racial profiling. The year was 1964. Sadly, such incidents as this still happen every single day – but only to people of color.

7. What do you think of “he sacrificed his immortality for her sake.”? (p.114)

Again, I see this as a bit of a stretch – another example of eisegesis. Was this mythic “man of the earth” really as mesmerized by this woman as our authors postulate? There’s nothing in the text to imply that he sees himself as some kind of a “sacrificial lamb.” He may have been just a bit stunned, at first, but he took a bite himself. The fruit – not her – was just too tempting.

8. Is there anything in our modern world that corresponds to ancient curses, especially curses from / by God? (p.116)

All that I can think of is that far too many people in our modern world – in the name of freedom – continue to be cursed by claiming that at any time, anywhere, and with anybody, they can do whatever they damn well want to do. It’s a free country, they say, so they should be free to do so. What’s worse about this curse, though, the consequences of this behavior have fallen onto all of the rest of us as well. But, no, God has nothing to do with it. In fact, much of the Bible says the exact opposite.

“The Garden of Eden in the Bible Outside of Genesis” (p.119-120)

“Original Sin in the Hebrew Bible?” (pp.121-122)

9. Is punishment the best response to sin, and if not, what is better? (p.122)

Call it sin or call it simply making bad choices, when such behavior does happen, I believe in restorative justice for the perpetrators rather than retributive justice. To my mind it’s the only “punishment that fits the crime” and goes beyond “paying one’s debt to society” for having done wrong. The heart of restorative justice is finding a way to bring wrong-doers back into the community and have them do what’s right – and then keep doing it. It’s meant to restore a real sense of how the one who has “sinned” still remains connected to society and belongs to the community. Both their needs, as well as the ones who’ve been wronged, must be met. Building, or re-building, the “sinner’s” skills is much more powerful and effective in creating the kind of healthy and safe community that we all wish we had. What’s more, it is far more enduring than the fear of punishment and retribution has ever been.

“Adam and Eve in Early Judaism” (pp.123-127)

“Later Jewish Tradition (pp.128-134)

10. How would you describe the relationship between sexuality and morality? (p.128)

They get misconstrued. They can and should be compatible. And yet, all too often, they are not – e.g. as in the corruption of businesses such as prostitution and pornography. You can be a fully sexual being and live out your entire life from that perspective while still remaining completely moral in your “lifestyle” – whether you are heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual or even asexual. Unfortunately, when one segment of society claims a certain way of sexual being to be immoral, while another part does not, what arises is more than just confusion, but outrage – on both sides.

11. Is the primary difference between Jews and Christians that Jews have questions and Christians have answers? If not, then what? (p.134)

I think that’s far too simplistic of a distinction. We both pose questions and answers; we just present them in different ways. And it’s not just that we have Jesus at the center point of our faith and the Jews have the Tanakh. There is much beauty, wisdom and power in the Jewish scriptures and tradition. They don’t only have the Tanakh. We don’t just have Jesus.

As our United Methodist denomination has attempted a balanced approach to this, we’ve turned to the, so-called, Wesleyan Quadrilateral: Scripture, Tradition, Reason and Experience. All four are meant to flow from one to the other and back again – each informing the other (Although I prefer the acronym REST because, for me, Reason and Experience ought to be primary – in the end, if it doesn’t make good sense, we should reform it or get rid of it.).

So, I like to think of our primary difference as simply being two religious points of view that remain in dialogue with one another. We’ve been having it for centuries – and it continues to this day. Jews have questions and answers. We have questions and answers. Sometimes our conclusions are in agreement. Often they are not.

Week 3 Questions

1 – Do you have any kind of modern interpretation of Logos? How does it work? 70

2 – What kind of connection do you see in the Royal WE of (say) English royalty and the plural use in the Bible? 73

3 – What kind of starting materials did God have “In the beginning…”? 76

4 – How does this initial “creating God” compare with your current understanding of God? 76

5 – Does the concept of ru’ach, in any of it’s forms, enter into your thoughts on a regular basis? What form is most common? 77

6 – How would you describe the difference between metaphorical wisdom of long ago and modern scientific wisdom? 83

7 – What advantage do Christians receive when their God “becomes human and walks among us.”? 87

8 – What is your feeling about a “divine council” as opposed to “One God”? 90

9 – So finally, who do you think the US is? 97

10 – Comments on the last paragraph? 98

Responses to Week 3 Questions

Chapter 3: “The Creation of the World” (pp.67-98)

“In the Beginning” (pp.69-73)

1. Do you have any kind of modern interpretation of Logos? How does it work? (p.70)

Yes. I take that word in its other literal meaning from the Greek λόγος – it also means “reason.” Does it make sense? Then, go with it.

However, as we know, somebody chose to translate it as “word” or “plan.” So, when the ancient Greek philosophical interpretation of this word spilled over into Christian theology, it became more than just a word; it became “divine reason.” It’s what was considered to be implicit in the cosmos – ordering it and giving it form and, finally, meaning. I think that it was Philo, that Hellenized Jew (c. 50 CE), who further speculated that the logos was an intermediary divine being (a.k.a. a demiurge) that existed somewhere between imperfect matter and perfect Form (i.e., God). He was of the opinion that it was the only way that we mere human beings could bridge the enormous gap between the Divine and our material world.

2. What kind of connection do you see in the Royal WE of (say) English royalty and the plural use in the Bible? (p.73)

For millennia – i.e., long before the creation of the Hebrew Bible, itself, and beyond – people were led to believe that those persons who ruled over them (such as pharaohs, emperors and kings) were, in some way, divine beings. They had to be. How else could they wield such power over the known world, people thought? When such a person says, “we,” he or she is calling upon the plurality of their divinity – i.e., they don’t just speak for themselves; they speak with the complete power of the divine that lives, moves, and has being in and through them. What “we” say goes. Because “we” speak, not only for ourselves, but for God.

The vestiges of that mindset remain even today. It would happen whenever the Pope chose to speak ex cathedra (in Latin, literally, “from the seat” of Peter or “from the teacher’s chair”). What he would be saying, therefore, would be infallible. Thankfully, most popes have never actually done that, because they’ve retained at least a modicum of humility. In my memory, it’s been used only once, by Pope Pius XII, in 1950, when he claimed the literal truth of the Assumption of Mary, the mother of Jesus – i.e., that she was taken (“assumed”) into heaven, body and soul, following the end of her life here on Earth. The only other time, I think, was when Pope Pius IX claimed that the Immaculate Conception was literal truth.

Interestingly enough, both of those popes chose the name Pius which, in Latin, is just the masculine word for “pious” – yet fully loaded with all of the other meanings given that word in English (Curiously enough, the feminine form of that name is Pia, but only became equivalent to recognizing a woman’s beauty or, at most, “wisdom” – and, of course, the Greek word for wisdom is a feminine noun, σοφία / sofia.).

To a lesser degree, and maybe a little less dramatically than all of the above, witness today how everyone (except, quite notably, one Donald J. Trump) is expected to genuflect before the Queen of England. As far as I know, though, only Queen Elizabeth I was known to have used the royal “we” when speaking. She was the queen back in the mid 1500s – sometimes called “the Virgin Queen,” even “Gloriana” – but, referred to by many of her subjects as just “Good Queen Bess.”

“Making Order from Chaos”

3. What kind of starting materials did God have “In the beginning…”? (p.76)

Heaven only knows. And She’s still pulling strings – so the theory goes – hidden behind a curtain.

4. How does this initial “creating God” compare with your current understanding of God? (p.76)

It’s not even close. I’ve come to think of “God” more as some kind of disembodied Force without any human qualities whatsoever – those were superimposed by the authors of scripture. God, for me, is Ultimate and Infinite Mystery. The less we assume that we know what (not who) God is, the more honest we would be.

5. Does the concept of ru’ach, in any of its forms, enter into your thoughts on a regular basis? What form is most common? (p.77)

I can’t say that it ever enters into my thoughts “on a regular basis,” but, if it did, it would be the ways in which I associate my own breath and breathing with the “breath of life” – that force which animates every living thing. Even plants breathe.

I also connect it with the Hebrew concept of נֶ֫פֶשׁ / nephesh, which is a bit different because it refers to the aspects of sentience that both human beings and animals have, however – and very significantly – the Bible never speaks of plants as having nephesh. It has, then, literally become translated as “soul” – although it’s most often translated as “life” in the English translations. Jewish scholars, however, would say that every sentient creation of God is (not “has”) a nephesh. So, in Genesis 2: 7, it’s not that Adam was given a nephesh but that Adam “became a living nephesh.” Curiously enough, when nephesh is connected with רוּחַ / rû’ach (in the “spirit” sense), it describes a part of humanity that’s immaterial – like our minds, emotions, will, intellect, personality, or conscience – as when we read in Job 7: 11, “I will speak in the anguish of my spirit; I will complain in the bitterness of my soul.” Those two underlined words are both the same in Hebrew – i.e., רוּחַ / rû’ach.

“Wind, Spirit, Wisdom, Logos” (pp.82-87)

6. How would you describe the difference between metaphorical wisdom of long ago and modern scientific wisdom? (p.83)

The former may address issues of truth based upon emotional, philosophical, psychological and/or theological observations – i.e., as manifestations through our spirit, intuition and conscience. The latter is based upon experimentally verified fact and peer reviewed consensus.

There is, however, a place in our world for them both.

7. What advantage do Christians receive when their God “becomes human and walks among us.”? (p.87)

It is, of course, metaphor. But many of us have taken great comfort from feeling as if God were as close to us as our breathing and heartbeats – that there is Something both profoundly immanent and yet extraordinarily transcendent about this One we’ve come to experience as “the ground of all Being” (a phrase made famous by the theologian Paul Tillich).

“Let Us Make Humankind...” (pp.88-92)

8. What is your feeling about a “divine council” as opposed to “One God”? (p.90)

Again, the authors of scripture have modeled all of this upon the royal courts of pharaohs, emperors and kings from their own culture. They were the one who sat in the seats of power in the only world everyone, at that time, knew. So, like their images for God, these “divine councils” and “heavenly courts” are sheer anthropomorphized speculation – at best. As our authors noted, what ends up is “people look like God and like the heavenly beings” (p.90) and, I would add, vice versa.

“Later Jewish Interpretation” (pp.93-98)

9. So, finally, who do you think the US is? (p.97)

I kind of agree with that “great medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides” that God is “both incorporeal and singular” (p.91). Unfortunately, “that was not the case for most of the Bible, where that deity is depicted in human form” (ibid.). More than that, we’ve no clear proof just who or what God is. But, that’s okay with me. My intuition tells me that there is Something More – a Force beyond our known reality – we just don’t know, for sure, what it is.

10. Comments on the last paragraph? (p.98)

I like it. While I hope that we all know, by now, that the whole biblical story of creation is imaginative fiction, it is one way that an ancient culture claimed a profound truth – i.e., it was important and that a “good world” must also be a well “ordered” one. What’s more, you and I have “a central and constructive role” to see that that happens. So, in the end, it’s up to us, not God.

But, then, that is the way that it should be. Isn’t it?

Week 2 Questions

1 – What literature other than the Bible do you read as having been written in an earlier time but now conveys information about our time? 44

2 – How would you determine whether a prophecy is near term or far in the future? 48

3 – How do you understand “...the curse of the law…” in Gal. 3:13? How were you influenced toward that understanding? 50

4 – How do you feel about prooftexting in general? 51

5 – How can you tell whether someone is using images or statues as Gods or as a focus for prayer (perhaps the first BAD and the second GOOD): 55

6 – What portion of the population, either Jewish or Christian, do you think would have access to polemic writings during the middle ages? 58

7 – Why do you agree with Michael Foucalut? 58

8 – If we assume that it is good to move from seeing one’s religion as “the only way” to “the best way” to “my way, but yours is fine for you”, what do you think is the most effective way to promote this movement? 61

9 – What would you most like to ask a new Jewish friend, and what would you most like to tell them (about religion)? 66

Responses to Week 2 Questions

1. What literature other than the Bible do you read as having been written in an earlier time but now conveys information about our time? (p.44)

Other than many of the books written by theologians of the past that Westar has referred to, the authors of ancient and recent history come to my mind.

How about a few of these:

• Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl

• War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy

• Grant, Ron Chernow

• Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fate of Human Societies, Jared Diamond

• Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam, Fredrik Logevall

• The History of the Ancient World, Susan Wise Bauer

• Democracy: A Life, Paul Cartledge

• The Crusades, Thomas Asbridge

• 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, Charles C. Mann

• 1776, David McCullough

Talk about revelations – and this just scratches the surface. I’m reminded of the observation of the philosopher, George Santayana, who said (and I’m paraphrasing), “Those who fail to learn the lessons of history will be condemned to repeat them.” Think of something like our war in Vietnam compared to the one we’ve been mired in for so long in Afghanistan.

2. How would you determine whether a prophecy is near term or far in the future? (p.48)

As it’s pointed out by our authors (p.44), biblical prophecy is not some kind of prescience, or other such mystical “crystal-ball-gazing” in which the prophet predicts an otherwise completely unknown future. Biblical prophecy was simply, yet profoundly, being able to see that current events were leading to a logical conclusion if a change was not made – even though the reality of this may be unforeseen by others. So, I think it makes little difference whether the prophecy is “near term” or “far in the future.” It just depends upon whether the changes being called for require imminent attention or not. The outcomes, however, could be very similar.

3. How do you understand “...the curse of the law…” in Gal. 3:13? How were you influenced toward that understanding? (p.50)

Traditional orthodox interpretations claim that Paul has just spent the previous verses arguing from the Old Testament itself that the Law can’t save us. The so-called “Judaizers” in Galatia were supposedly trying to convince the Christians there that while they needed to follow Jesus, in addition they needed to continue to follow the Law of Moses (cf. Gal. 2:4). There’s some sense in that. However, Paul seems to be claiming that Deuteronomy, Habakkuk and Leviticus show us that to live by faith and also to live under the Law just isn’t compatible – according to him the two can’t be merged in any way. Again, traditional orthodoxy claims that we’ll always be lawbreakers; we just can’t help ourselves. We’re cursed by that conundrum. The traditional answer? Jesus, as the Christ, did for us what we couldn’t do for ourselves. He redeemed us from “the curse of the law.”

It’s worth mentioning here that the word “redeemed” has its root in the Greek word εξηγορασεν /exegorasen – which refers to “buying someone out of slavery.” According to the traditionalists, then, Paul is saying to us that Jesus, as the Christ, did just that for us by taking our curse on himself. Paul then uses the classic prooftext from Deuteronomy to say that everybody hanged on a tree is cursed (Deuteronomy 21:23) – so, even the way Jesus was killed was evidence that he willingly became cursed in our place.

How, in the world, can that be claimed as “good news?” But to orthodox Christians that’s the essential meaning of Jesus’s entire life in a nutshell. That’s what it means to be “saved by faith.” It makes no sense to me at all. It never has.

4. How do you feel about prooftexting in general? (p.51)

I think we’ve had far, far too much of it. The seduction to make the text say whatever you want it too say has been so misused as to lead one to come to the logical conclusion that it’s all pure fiction so not even worth considering. That is a tragedy, because there actually is much truth, power and beauty in scripture that then is lost. It also reminds me of something John Dominic Crossan emphatically said:

“My point, once again, is not that those ancient people told literal

stories and we are now smart enough to take them symbolically, but

that they told them symbolically and we are now dumb enough to

take them literally.”

5. How can you tell whether someone is using images or statues as Gods or as a focus for prayer (perhaps the first BAD and the second GOOD)? (p.55)

Just ask them. This is why the use of icons has been so misunderstood (leading to the very word “iconoclast” – meaning “a breaker or destroyer of sacred images” or “a person who attacks cherished beliefs as being based on error or superstition.”). Icons, as with other such artistic images or statues, were actually only meant to be “windows into the Sacred,” not a vision or Presence of the deity itself.

6. What portion of the population, either Jewish or Christian, do you think would have access to polemic writings during the middle ages? (p.58)

I’d say less than 5% – maybe even as low as 1% – because the vast majority of the population during that time was simply illiterate.

7. Do you agree or disagree with Michael Foucault? (p.58)

At the risk of sounding like I’m equivocating, in some ways I think he’s right – especially when polemics clearly degenerate into “a power game that obstructs the ability to find the truth” and one or both in the game confront “not a partner in search for the truth but an adversary, an enemy who is wrong.” I know exactly what he means. I’ve experienced just those kinds of moments throughout my ministry when I’ve attempted to be in dialogue with Christian fundamentalists. There never was a dialogue. There was only diatribe. So, a long time ago, I gave up attempting to engage such people in any meaningful conversation – let alone anything like a dialogue. As our authors rightly point out, “Words matter, and words can do harm” (p.59) – especially when they’re intentionally meant to do so.