This book study begins May 3, 2020 only on Zoom.

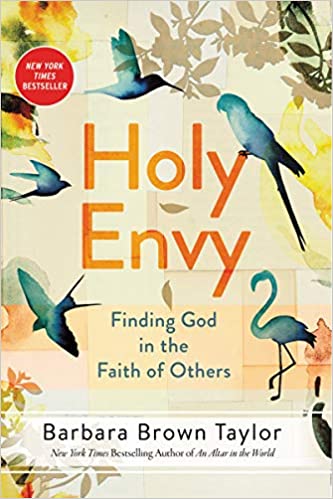

In “Holy Envy”, Barbara Brown Taylor writes about her many years of experience teaching Religion 101, World Religions, as an introductory religion course at a small private college in northern Georgia. Her course covers Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, leaving out a huge number of other, smaller religions. The book title refers to characteristics of religions other than her own Christianity that cause her envy. As an ordained Episcopal Priest with years of leading local parishes, she has a perhaps too solid foundation in her own religion. Seeing others, and teaching them to college students has shown her a new view of how religions can and should work in the world.

This is not my usual content for study books, as you can easily see by looking through this website. It was recommended by one of our readers and will be a good book for our group to work on over a Zoom connection while we shelter in place awaiting the end of the COVID-19 virus pandemic. At least we won’t be killing each other between computer screens as we might have done sitting next to each other in a small living room. Another difference in this book study is that we will be using a study guide by SmallGroupGuides.com rather than my usual questions. I want to see what kind of difference this makes.

Unfortunately, there will be no cookies….

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Week 7 Questions

CHAPTER 11: THE GOD YOU DIDN’T MAKE UP

1. Think about your own spirituality. How do you filter what new information to include in your picture of God? Whom do you trust to speak to your faith, whom don’t you trust, and why? When your spirituality has shifted, what has caused those shifts?

2. Taylor concludes that what can help most in getting beyond her own limited perspective is not trying to be proficient in all religious languages (p. 190) or giving up speaking her own (p. 193), but being authentically human in how she talks and listens to others. What does it mean to you to be authentically human? Who are your best role models?

3. As difficult as it may be to love those who look, think, and act differently from us, Taylor notes that it is perhaps the best way to get close to the God we didn’t make up (p. 195). Can you share an instance where you were called upon to show kindness to a stranger, or when you were a stranger who received surprising kindness from someone else? What did these experiences teach you about your own humanity, and about God?

CHAPTER 12: THE FINAL EXAM

1. Taylor discovers that her relationships with complex, surprising religious strangers have benefited her faith more than religious certainty and solid ground (p. 213). In your own spiritual journey, what kind of certainty has remained important to you and what kind has not? How do you feel about standing on changing ground? What relationships have shaken your spiritual foundations and what has the outcome been for you?

2. Taylor’s baseline for becoming Christian is “to extend the same care to every human being that I wish for myself, to treat every human being as if he or she were Jesus in disguise” (p. 214). What are your thoughts about this? What is your definition of what it means to be Christian?

EPILOGUE: CHURCH OF THE COMMON GROUND

1. Though Taylor spent half a lifetime near the center of her religion, she now finds herself on what Richard Rohr calls “the edge of the inside” (p. 217). Where are you in relation to the center of your tradition? What benefits and drawbacks do you experience in this position? How do you feel about where you are?

2. When Taylor visits the Church of the Common Ground, which meets outdoors in a public park in Atlanta, the bishop’s words strike a new chord with her: “As different as we are, whatever concerns we bring, we are all one” (p. 222). Having chewed on this book, what do the words “we are all one” mean to you? What do you affirm in them? What do you question in them?

3. How has this book challenged your understandings of what it means to practice true religion, to be a good person, to be on the right spiritual path? Has anything changed about how you relate to people of other religious traditions or how you practice your own faith? If so, what do you think you will do about it?

Reply to Week 7 Questions

Chapter 11: “The God You Didn’t Make Up”

1. Think about your own spirituality. How do you filter what new information to include in your picture of God?

It sounds a bit simplistic, on the surface, but my first filter is that that “picture of God” has got to make good sense to me – in some ways that includes consideration of current scientific discovery. A very close second filter, however, is a more mystical, intuitive way of perceiving. If the “picture of God” presenting itself leaves me with feelings of awe, love, wonder and deep shalom, I will stop, first, and meditate on the experience (i.e., question, seek to find and know more), but then enter a time of deep contemplation (i.e., being very still, quieting my mind, and opening myself while I effortlessly wait for whatever comes). Such “filtering” times as these have led me to make profound connections with the Sacred. I trust these two approaches the most and, in a very concrete way, they’re always in dialogue with each other.

Oddly enough, however, the God most often portrayed in the Bible is one I rejected long ago.

Speaking of other filters, I do resonate with the statement that Taylor makes about this journey:

“The more I learned about the religions of the world, the more I became

convinced that they were all pointing to the same sacred mystery beyond

all human understanding” (p.189).

[Note: Just a postscript on the differences between “meditation” and “contemplation” – as I’ve come to understand them. While both have the goal of moments of revelation and insight, meditation is much more active while contemplation is not. One of the reasons why most of us First-World-western thinkers have great difficulty (at least initially) with contemplation is because we are more used to the pursuit of knowledge than we are the simple reception of it – we want to “go after it” rather than “let it come to us.” While one approach may not be any better than the other, both can lead to profound ways of knowing – especially of the Holy.]

• Whom do you trust to speak to your faith, whom don’t you trust, and why?

In the areas of spirituality and my faith journey (the two are inextricably connected), I trust the scholars of the Westar Institute the most because their biblical scholarship is impeccable. What’s more, I trust those who remain to have doubts far more than I do those who claim to have absolute certainty. That’s why my first impression of Church doctrine (certainly dogma) was often to first say to myself, “I doubt it.” I need some kind of proof. And, as I’ve stated above, I need it to make sense. In the end, it must feel right – so, finally, I’ve come to trust my own intuition throughout my faith journey.

• When your spirituality has shifted, what has caused those shifts?

Fundamentally, it’s when my doubts have overcome an earlier acceptance – when I can no longer believe in what I once thought that I did (e.g., biblical concepts of God, the so-called virgin birth of Jesus, the assumption of miracles and the divinity of Jesus, the doctrine of original sin, the nature of damnation and salvation…I’m sure the list goes on).

2. Taylor concludes that what can help most in getting beyond her own limited perspective is not trying to be proficient in all religious languages (p.190) or giving up speaking her own (p.193), but being authentically human in how she talks and listens to others. What does it mean to you to be authentically human?

We cannot be a copy of any other human being; we must be true to ourselves – let’s begin there. To be authentic when it comes to religion and spirituality, then, means that I have to represent my own true nature and belief. What’s more, as much as possible, the positions we take and the opinions that we have should have an origin that can be supported by unquestionable evidence – i.e., verified, convincing, credible, trustworthy, factual, …authenticated if you will. If you can do none of that, I’d say you weren’t being “authentically human.”

• Who are your best role models?

They began with my own father and his father; they both seemed to me to embody all that it meant to be a trustworthy and truly authentic human being. I consider myself profoundly blessed to have been nurtured by them and had them influence me during those early formative years of my life.

In my vocation as ordained clergy, it’s been the scholars of the Westar Institute (a.k.a. the “Jesus Seminar”). In my concurrent vocation as a certified Spiritual Director (It would be more accurate to interpret the second word of that title as “companion.”), it’s been Sister Mary Ann Scofield – my mentor in that discipline – of the Mercy Center in Burlingame, along with others within Spiritual Directors International.

3. As difficult as it may be to love those who look, think, and act differently from us, Taylor notes that it is perhaps the best way to get close to the God we didn’t make up (p.195). Can you share an instance where you were called upon to show kindness to a stranger, or when you were a stranger who received surprising kindness from someone else?

There must be more than just this, but what comes to mind for me is the time that I “received surprising kindness from someone else.” I was recovering from surgery at the Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland in March of 1993 and I’d just been in an extended conversation with a colleague who’d visited with me for awhile but then had left. A Roman Catholic priest stopped by soon afterward (I still don’t know whether or not he was an official military chaplain.) and he offered to have a moment of prayer with me. Well, not wanting to appear disagreeable, I graciously accepted his offer. To this day, I don’t remember what he said, but I do remember the gentle touch of his hand on my shoulder and how I felt hearing his quiet words of blessing and the comfort that he gave me. He didn’t know me from Adam, but I became aware of just how deeply touched I was by his kindness – and how much I’d needed such a simple gift. When he left, I silently wept with thanksgiving. The difference that I felt between a friend’s casual and chatty visit and this priest’s presence by my side was startling. I’ve never forgotten it.

When presented with such priestly moments ever since then, myself, I’ve tried to say very little but offer just such a gentle touch and the same kind of compassionate presence to someone who seems to need it.

• What did these experiences teach you about your own humanity, and about God?

No matter what our religious beliefs and practices, I’ve come to recognize that we all are able to recognize and feel deeply blessed by the gentleness and kindness of such a stranger. There are times when we don’t need advice, we don’t need more information or direction; what we need is simply compassion and care. Just as significantly, we can offer that very same kind of presence to others – at any time, at any place, under any circumstance, and with anybody.

Where God comes into this, oddly enough, I’m still reckoning with. Jonathan Sacks has a significant comment to make in that regard near the end of this chapter: “The supreme religious challenge,” he says, “is to see God’s image in one who is not in our image” (p.200). That led Taylor to observe that “the stranger…may offer us our best chance at seeing past our own reflection in the mirror to the God we did not make up” (Ibid.).

Chapter 12: “The Final Exam”

1. Taylor discovers that her relationships with complex, surprising religious strangers, have benefitted her faith more than religious certainty and solid ground (p.213). In your own spiritual journey, what kind of certainty has remained important to you and what kind has not?

I think that Huston Smith both addresses this question and then answers it, to some extent, as Taylor quotes him for her chapter heading: “So what do we do? …. We listen” (p.203). It has to at least begin there – by paying attention to revelations of the sacred beyond our preconceived notions of how they have come to us. We need to listen to other voices than just our own. So, I fervently agree with Taylor’s own certainty when she says that “when my religion tries to come between me and my neighbor, I will choose my neighbor. … Jesus never commanded me to love my religion” (p.208).

I addressed another certainty which I have in my response to question #3 in Chapter 10 – essentially, that there simply is far, far too much that we do not yet know about the nature of reality and any divine role in it. We still have much to learn about it all.

So, where I once held some degrees of certainty about Christianity and the teachings within our Bible, they’re not as important to me as they once were. While they have given me both a wonderful foundation and direction for my own spiritual journey, there is a lot yet to be revealed – and some of it will come from a different direction.

• How do you feel about standing on changing ground?

I feel quite comfortable, actually – even revived and energized to continue the journey. I am saddened, though, by the ways in which I’m viewed as an outsider by former friends and colleagues within my own denomination (or by those who would label me with their orthodox definition of a heretic). In many ways, even members of my own family aren’t quite sure about the new directions that my spiritual journey has taken me. I think, for some, it’s just that they’re more content to remain within the boundaries of the religious beliefs that they’ve long been given by our tradition and are uncomfortable seeing its doctrines and worship reworked (e.g. especially the prayers, hymnody, and other rituals). Many still in the pews of our churches today feel as if their faith is being undermined and, therefore, is under threat.

It is. And I’ve been at this longer than most people know. I think that I’ve shared with this book group that as early as my time in seminary a professor once cautioned me by saying, “Be careful how you shake the foundations of the faith of the people that you’re there to serve, Doug – unless you have something better to replace it with.” The problem has come in the definition of that phrase “something better.” While I’ve felt that a radically new reformation is called for, regrettably, the majority remaining in the Church have not.

• What relationships have shaken your spiritual foundations and what has the outcome been for you?

I think those relationships were at least forty or more years ago as my role as a counseling psychologist within the public secondary school system then led me into the ordained ministry. Every time that I bumped heads with orthodox positions, however, my spiritual foundation was shaken, so I turned to innovative theologies and other practices of ministry that I found compelling – because I’ve always been unorthodox.

Not surprisingly, then, I found the candidacy process into the ordained ministry to be somewhat of a challenge – especially when my theology ran counter to the doctrinal positions of The United Methodist Church. By then, however (Thank you, Duke University!), I could offer cogent and reasonable alternatives that at least kept me in the tent and not had me being kicked out the door. Some who examined me, however, did suggest that I was in the wrong denomination. Maybe so, but my own United Methodist congregation there in North Carolina had thought that I had the “gifts and graces” for ministry or they wouldn’t have sponsored me. For many of these reasons above, though I finally concluded that I had to leave the deep South and come back to California – the Conferences of United Methodism are that dissimilar.

But I liked what I’d first learned about John Wesley’s teachings in the St. Luke United Methodist Church in Sanford, North Carolina: “If your heart is as my heart, then give me your hand,” Wesley would say with truly catholic spirit – because his spirit was an ecumenical one. He preached that our way of doing theology and church must strike a balance between scripture, tradition, experience and reason (a.k.a. the Wesleyan Quadrilateral). But while most United Methodist conservatives want to emphasize scripture and tradition at the expense of the other two sides, I wanted to emphasize reason and experience – with scripture and tradition there only to help hold up the other two sides.

Obviously, it wasn’t a square quadrilateral in either model! “Give it a R.E.S.T.,” I’d say! But the prevalent approach that remains much the same across Methodism looks this way: Scripture must be primary (and, I maintain, dogmatically interpreted) in directing all of the Church’s theology and ministry. Next, Tradition must be adhered to often at the cost (in my opinion) of Reason and Experience. The result – in much of current United Methodist orthodoxy – is that the model looks less like a balanced four-sided structure and more like four boxes, with Scripture the largest box, followed by the next box of Tradition, and only then Experience – with Reason hemmed in from all sides and blocked from being given equal weight at all next to those first two big boxes. Okay, so my quadrilateral is “out of balance” in the other direction as well. I just can’t lean the other way.

The outcome, though, is that while we’ve had a strained relationship over the last forty years – The United Methodist Church and I – we’ve been able to make it work. I’ve served some wonderful congregations filled with warm-hearted, compassionate, committed and loving people. For the most part, I’ve felt fulfilled in my vocation and many of my closest friends continue to be members of The United Methodist Church. Go figure.

2. Taylor’s baseline for becoming Christian is “to extend the same care to every human being that I wish for myself, to treat every human being as if he or she were Jesus in disguise” (p.214). What are your thoughts about this?

Why does it have to be “Jesus in disguise?” Everybody should receive such care. That’s why I liked Taylor and her husband, Ed’s, “first amendment to the Golden Rule” mentioned back in Chapter 11 (p.195):

“…which is not ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,’ but

‘Do unto others as they would have you do unto them (instead of thinking

they are just like you).’”

Now, that is revolutionary. I like that approach.

• What is your definition of what it means to be Christian?

Follow Jesus.

Epilogue: “Church of the Common Ground”

1. Though Taylor spent half a lifetime near the center of her religion, she now finds herself on what Richard Rohr calls “the edge of the inside” (p.217). Where are you in relation to the center of your tradition?

Okay, at the risk of sounding argumentative, who defines what and where “the center” really is? If you’re calling it the “Tradition,” I’m not even keeping “an eye on the door” (as Taylor puts it). I’m looking the other way. I am filled with mixed emotions, but glad to leave that tradition behind. My attention is toward what’s down the path, around the corner, or on the other side of the hill. It may be that the Real center – at least for me – is somewhere else.

• What benefits and drawbacks do you experience in this position?

Like the “Golden Rule” and the acts of love and compassion shown by Jesus, I’d say that I’ve received many blessings and immeasurable benefits from my spiritual journey within the Church. The drawback is that this same Church remains to be so stuck in the past that it can no longer envision a different future – in fact, in many overt as well as subtle ways, it resists any kind of meaningful reformation.

• How do you feel about where you are [now]?

I am content. I am loved. I count many – both family and friends – whom I love in return. And my spiritual journey is as compelling and dynamic as it’s ever been.

2. When Taylor visits the Church of the Common Ground, which meets outdoors in a public park in Atlanta, the bishop’s words strike a new chord with her: “As different as we are, whatever concerns we bring, we are all one” (p.222). Having chewed on this book, what do the words “we are all one” mean to you? What do you affirm in them? What do you question in them?

We share the same nature and needs as any other human being – in that sense, yes, “we are all one” – and yet we remain to be divided in so many ways. Even Taylor recognizes this separation when she says:

“There is no such thing as religion. There are only religious people, who

embody the scripts of their faith as differently as dancers embody the steps

of their dances” (p.216).

What the bishop was trying to say there, I think, was that in spite of our differences we have the potential to recognize the values that we have in common: the need to love and be loved, the need for sustenance and safety, the need for healthy maturation in a supportive environment, the need for equality and justice…and so on. I would agree. To me, that is religion. How we practice these values may be the only difference between us.

3. How has this book challenged your understandings of what it means to practice true religion, to be a good person, to be on the right spiritual path?

I wouldn’t say that this book has “challenged” me as much as it’s reaffirmed for me that I am “on the right spiritual path.” Each of us should be challenged, however, by people like that petite and very angry African American woman (pp. 220 ff.). As we’ve all been reminded, lately, she has been denied “common ground” solely because of her race. Yet nobody there really seemed to notice. They just wanted her out of their way. Maybe the “Ambassador” finally did connect with her and really listened. I fervently hope so.

• Has anything changed about how you relate to people of other religious traditions or how you practice your own faith? If so, what do you think you will do about it?

Not really – I don’t attend traditional worship services any more, though. But then I’ve been on a pretty unorthodox path for most of my life. In that regard, I’ve always identified, very much, with this well-known poem by Robert Frost; it’s been a perfect metaphor for my own spiritual journey:

The Road Not Taken

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

I have been profoundly grateful for having taken exactly such a path.

Week 6 Questions

CHAPTER 9: BORN AGAIN

1. In Taylor’s rereading of the story of Nicodemus coming to Jesus in the night (pp. 163–68), being “born again” means acknowledging all that you don’t know about God and being freed by that unknowing. Are there things you were once certain of that you don’t know about anymore? How does Taylor’s understanding of being “born again” compare to yours?

2. Taylor suggests we should keep our ways of thinking and speaking of God fluid, lest our theologies become “theolatries—things we worship instead of God, because we cannot get God to hold still long enough to pin God down” (p. 171). How important is orthodoxy (correct theology) to you?

3. Though Taylor has moved away from the traditional center of Christianity, she has learned from friends in other religions to see the good in her tradition (pp. 171–73). If you have experienced a similar shift in your religious perspective, what new views do you have of your tradition?

CHAPTER 10: DIVINE DIVERSITY

1. In Taylor’s reading of the Tower of Babel story, God decided it would be good for humans to speak a diversity of languages, slow down, and work harder to understand one another (p. 181). Though it feels safer to go back to Babel, where everyone speaks the same language, Taylor believes it’s important to live in spaces of diversity even if they include the potential for misunderstanding and require more intentional communication. How do you feel about living among differences and trying to have conversations with people who think differently than you? What kinds of diversity are valued in your community and what kinds are not?

2. Do you think it’s possible to have a real conversation with someone if you are unwilling to entertain the idea that you could be wrong, or at the very least the idea that there could be more than one way to see a given issue? How willing are you, at this point, to take on new perspectives (religious, political, or otherwise) and surrender the primacy of your own?

3. Taylor admits at the end of the chapter that having holy envy, and entertaining a variety of religious visions, might require a level of maturity in one’s faith tradition. At what point in the religious journey is it appropriate to begin reimagining the stories of your tradition? If you are in a position of passing your faith onto children or those new to the faith, how do you give them truths to hold on to without being rigid about those truths?

Responses to Week 6 Questions

Chapter 9: “Born Again”

1. In Taylor’s rereading of the story of Nicodemus coming to Jesus in the night (pp.163-168), being “born again” means acknowledging all that you don’t know about God and being freed by that unknowing. Are there things you were once certain of that you don’t know about anymore?

As a child and teenager, I took to heart that “the Way” God had been revealed to us was in “His Son,” Jesus. Christmas was more magical to me than Easter, but between those two events his life revealed all that we needed to know about God. Growing into my adulthood, however, I no longer saw it that way. There just seemed to be much, much more to the story. The boundless aspects of the nature and reality of God seemed to reach far beyond the Christian story – just how far, I had no idea.

At first, that unknowing and exploring of the Mystery which is God, for me, didn’t feel like “being freed” at all. I felt lost in the wilderness. It was as I continued to explore the wonder and beauty of nature and the cosmos (truly wondrous for a child growing up on a tropical island in the Caribbean as I did), that all of the doctrinal and anthropomorphic imagery of God slipped away. And yet, I still felt a Sacred presence that drew me deeper into the Mystery. It didn’t feel as dramatic as being “born again” – at least not in the way that seems to be modeled by the conservative evangelical church as an abrupt black-to-white, “I once was blind, but now I see” kind of shift (What’s more, I never have felt like the “wretch” written and sung about in that hymn, “Amazing Grace”.). And yet, … I was amazed by the grace and beauty of life that I saw and experienced all around me and I wanted to know more about it. I still do.

It’s odd, then, that the more I explored the depths of my faith, the less certain I was about all of it. As I’ve alluded to, before, it was my associate membership in “The Jesus Seminar” (a.k.a. the Westar Institute) that revived my ministry – I’d even entertain images of both “new birth” and “salvation” coming from that, now, nearly quarter-of-a-century association with those wonderful biblical scholars. It renewed my religious commitment and my purpose in pursuit of that quest – as I would now put it: to know and be known by that Sacred Mystery that infuses all of creation (so, my panentheistic leanings). If it is “being born again,” for me, it feels very much like strolling ever deeper into the wonder and mystery of all that’s Holy.

• How does Taylor’s understanding of being “born again” compare to yours?

I find that her understanding is very close to my own. To begin with, I think we ought to look again at just how Taylor does understand this new birthing. Here are some clues from this chapter. She says:

* “I thought it might help if I told the students that their old life was over…. ‘You are about to enter a period of deep unknowing, …. So relax if you can, because you are not doing anything wrong. This is what it means to be human” (p.163 – and, these last two statements, are repeated on p.167).

* “This birth Jesus is talking about, then, is not plain birth…the mother is the Spirit” (p.165).

* “No one knows where the Spirit comes from or where it goes. No one”…. ‘You do not know,’ Jesus says…. The Spirit gives you life. She comes and goes. She is beyond your control” (pp.167-168).

* “I gained new respect for what it means to be agnostic…all it really means is that you do not know, which according to Jesus is true of everyone who is born of the Spirit” (p.168).

* “Even if you are still working at it, that is the mustard seed” (p.169).

* “When she drops me off in unfamiliar places, I need to pay attention…. She gives life to all creation. I have plenty more questions, but the answers are not vital as long as God the Spirit keeps breathing on me” (p.170).

* “To walk the way of sacred unknowing is to remember that our best ways of thinking and speaking about God are provisional. They are always in process – reflecting our limited perspectives” (p.171).

And, finally, there’s this little gem of Taylor’s near the end of the chapter:

* “…part of being born again is looking for ways to return the favor….” (p.173).

All of this sounds very much like the biblical understanding of σοφία or sophia to me – which is a feminine noun and the word in Koine Greek for “wisdom.” Never mind the secret delight that our author seems to take in imagining that the “third person of the Trinity” is like a woman, I agree with her conclusion from start to finish that being “born again” essentially means a recognition that, not only do we not know it all, we never will. But we should continue in this search for wisdom as long as we live.

Over the years, the way that I’ve presented this phenomenon is to say (to myself as much as to others), “Just as soon as we have one question answered – if we’re paying attention – we will be pushed into a deeper question.” To put it in another way (carrying through with Taylor’s imagery) we are being invited to enter a time, yet again, of labor and awaiting another new birth. I’ve come to cherish the deep spiritual truth of this way of understanding being “born of the Spirit.” But I wonder what my conservative evangelical friends and colleagues might say about it when they assume that being born again happens only once – when it ought to be happening again and again and again.

2. Taylor suggests we should keep our ways of thinking and speaking of God fluid, lest our theologies become “theolatries – things we worship instead of God, because we cannot get God to hold still long enough to pin God down” (p.171). How important is orthodoxy (correct theology) to you?

I’m sure that I’ve borrowed this statement from somewhere else – but I’ve used it long enough to consider that it’s mine: “We either worship God or we worship things that we’ve made into our god.” Fill in the blank what those “things” might be; the list is long. So, not surprisingly, orthodoxy (or “correct theology”) for me never has been the answer; it’s the root cause of the problems that we’ve always had with the institutional Church – at least since Emperor Constantine in the 4th century who convened the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, giving rise to the Nicene Creed. [If you’re interested, read something of its convoluted history here:

https://theologyimpact.com/what-are-the-essentials-of christianity/?gclid=CjwKCAjw2uf2BRBpEiwA31VZj0DdoE9WVvXftLT-HnRtm6tRyUNNj_bcOpf4rRK9dscpeKKqTKxeNxoCU_cQAvD_BwE]

So, Taylor’s exactly right when she says, earlier in that paragraph there:

“To walk the way of sacred unknowing is to remember that our best ways

of thinking and speaking about God are provisional. They are always in

process – reflecting our limited perspectives, responding to our particular

lives and times, relating us to our ancestors in the faith even as the flow

out toward the God who remains free to act in ways that confound us” (p.171)

I resonate, very much, with that perspective of being confounded by and yet embracing a “sacred unknowing” such as that.

3. Though Taylor has moved away from the traditional center of Christianity, she has learned from friends in other religions to see the good in her tradition (pp.171-173). If you have experienced a similar shift in your religious perspective, what new views do you have of your tradition?

As most of my closest friends know, the “new views” that I have of our tradition have come, both from my association with the Westar Institute (a.k.a. the “Jesus Seminar”), as well as from my ongoing education as a theologian – and that education goes a long way back, only culminating in my master’s degree in theology from Duke University. I’ve been privileged to have had excellent teachers – including my own father and grandfather. The most profound “new view,” however, has been that I deny the divinity of Jesus and fervently reclaim his humanity and role as a Jewish prophet. At the same time, my view of God has profoundly changed and continues to be decidedly unorthodox – as anyone can clearly see revealed here in these pages.

Chapter 10: “Divine Diversity”

1. In Taylor’s reading of the Tower of Babel story, God decided it would be good for humans to speak a diversity of languages, slow down, and work harder to understand one another (p.181). Though it feels safer to go back to Babel, where everyone speaks the same language, Taylor believes it’s important to live in spaces of diversity even if they include the potential for misunderstanding and require more intentional communication.

• How do you feel about living among differences and trying to have conversations with people who think differently than you?

It appears, once again here, that Taylor has appreciated and been deeply affected by conversations that she’s had with Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. I agree with her statement in this:

“It is a great thing to see something familiar from an unfamiliar angle for the

first time, even if it is because you have been worried and lost for longer than

you would have liked” (p.176)

That feeling of being “worried and lost” for longer than I liked used to be true for me, too.

As she addresses the fact that the truly great world religions have a lot in common, she also says this:

“Whether they confess faith in the same creator-God, they agree that the

truth of their teaching hinges on how people treat one another: with partiality

or justice, with dishonor or dignity, with cruelty or compassion” (p.177).

Amen to that, as well.

Never mind, then, that the Tower of Babel story is a symbolic myth, I do agree with Taylor’s acceptance of that man from Ghana’s counternarrative, Emmanuel Lartey, whose interpretation of the story was this:

“…it was not about God’s judgment on diversity but God’s judgment on the

dominance of one people, with one language, whose wish to make a name

for themselves took over their lives. [So,] the moral of the story is that God

favors the diversity of many peoples over the dominance of any one people” (p.179).

It isn’t that we have a choice to either accept or reject diversity, the reality is that we do live among people who “think differently” from us. When true dialogue can happen, then, I’m all for it. There may be “more than one way to say something important” (p.181). However, when ideologues refuse to even entertain alternative points of view, I’ve learned from experience to simply walk away – trying to have any true give-and-take with such people is impossible. They must be right while others must be wrong. Period. Having a conversation with them would be like trying to talk sense into Donald J. Trump – it’s either his way or no way.

• What kinds of diversity are valued in your community and what kinds are not?

Remarkably, in retirement, my wife and I live in a very heterogeneous community. Unfortunately, those of different races, ethnicities, or different religious or political points of view – for the most part – have chosen to convene and interact with others who are just like them. Regrettably, to a great extent, I do the same, myself. All of us cling to “our kind of people.” While it’s no excuse for not, then, taking the time to reach out to those who are different from us, it remains to be an almost biological trait of all human beings.

On the positive side, though, where my neighbors and I do come together (interacting out-and-about the community, and in shared events or programs), most of us do choose to look beyond our differences and appreciate, instead, what we have in common: our shared humanity. It’s in specifically circumscribed groups where race, ethnicity, or particular religious and political views become the focus that we choose to affirm our separateness. Our Napa book group is such an example – but, I would maintain, not in any bad way.

2. Do you think it’s possible to have a real conversation with someone if you are unwilling to entertain the idea that you could be wrong, or at the very least the idea that there could be more than one way to see a given issue?

No. When someone begins from such a rigid position – where a person is even “unwilling to entertain the idea” that he or she might be in error, or maintains that there’s only “one way to see a given issue” – no real conversation will ever take place. Meaningful conversation is only possible when true dialogue (as opposed to vitriolic debate) happens – i.e. when each side listens respectfully to the other and tries to at least appreciate, if not completely understand, a different or even, especially, an opposing point of view. But it can happen.

• How willing are you, at this point, to take on new perspectives (religious, political, or otherwise) and surrender the primacy of your own?

I think that I remain open to at least entertaining “new perspectives” of reality, but I have to admit that, at this point in my life, it would be very difficult for me to simply “surrender” most positions that I hold nearest and dearest to my heart – especially as it relates to my concepts of justice, equality and my own deeply personal spirituality. I would need proof – e.g., as in irrefutable scientific or sociological proof – to give any of that up.

At the same time, I would never ask others to “surrender the primacy” of their positions – unless there were proof that those positions, in fact, were unjust, discriminatory or detrimental to the health and safety of others. What’s more, we must not continue to remain stuck in a society that favors only the wealthy and powerful – where their way is the only way and the impoverished and powerless are forever “kept in their place.”

3. Taylor admits at the end of the chapter that having holy envy, and entertaining a variety of religious visions, might require a level of maturity in one’s faith tradition.

• At what point in the religious journey is it appropriate to begin reimagining the stories of your tradition?

I think we reached that point long ago – when someone or group of people first offered the possibility that those stories may not have happened in the ways in which they were told. This is one of the reasons why we have 66 different texts in the Bible – it’s not one story, but many. It’s entirely appropriate, then and now, to begin to imagine a different meaning for them all. Regrettably, most devoutly religious people don’t see it that way. That reminds me, as we studied theology and the origins of the Bible at Duke University, we had a not so facetious saying (emanating from some of us): “In the beginning was the Word…and the Word was changed.” To a great extent, that is the history of all human experiences of the sacred – no matter what their origins.

• If you are in a position of passing your faith onto children or those new to the faith, how do you give them truths to hold on to without being rigid about those truths?

As many of you know, I have been and still am in such a position. I’ve been helped by those sages of ancient history who would often preface their stories by saying something like this: “It may not have happened exactly like this; nevertheless, it is true.” Given my understanding of religion (i.e., that it re-presents the values we all have in common), I’ve invited children in confirmation classes at church, as well as my own children and grandchildren, to consider that we should be able to see the truth that each of us holds sacred even if it has been revealed in different ways, in different languages, from within different cultures, and from people who may have experienced the same reality but from different perspectives. The different ways in which the so-called “Golden Rule” has been, first, experienced and, then, expressed is a prime example of this dynamic.

If there are any “truths to hold on to” it must begin with the recognition that our knowledge is limited. Again, as Taylor rightly has pointed out, we cannot know it all; but, being “born in the Spirit,” we can embrace the discoveries that we have made and look forward to the next one. Through it all, we need to make the best use of the scientific methods available to us so that we don’t make the same kind of mistake that the Church did with Galileo and Copernicus as it declared their idea of a heliocentric solar system to be heresy. A central truth in all of this is to finally admit that, all too often, we don’t even know just how much we don’t know. The universe and our relationship with it continues to be filled with mystery.

So let’s keep talking with each other about all of this and discover the answers together.

Week 5 Questions

CHAPTER 7: THE SHADOW-BEARERS

1. On page 129, Taylor says that September 11 changed the way Americans view Islam, resulting in what President Bush called “a quiet, unyielding anger,” (p. 129), that continues today. What fears do you have around terrorism? Where do they come from? How do they affect your perception of everyday Muslims?

2. Referencing author Jonathan Sacks, Taylor identifies “groupishness” as the source of our violence, more than religion or secularism (p. 131). Where do you see “groupishness” in your own community? How can we maintain a positive sense of group identity without needing to diminish the value of those who do not belong to it?

CHAPTER 8: FAILING CHRISTIANITY

1. Have you ever looked at your faith from the outside, as Taylor did, through the eyes of historians and religion scholars? What has that lens revealed to you?

2. Taylor describes learning from people of other faiths about “how bruised they were by Christian evangelism,” especially since their consensus was that “Christian evangelists are not very good listeners” (p. 148). What is your experience of Christian evangelists? Have you ever witnessed Christian evangelism done in a way that seemed respectful to others and their faiths? Who do you think is the best judge of whether evangelism is respectful or not?

3. What do you think of Taylor’s idea that Jesus alone is the arbiter of salvation in his name” and that his saying about being the way, the truth, and the life “puts him in charge of deciding who is on his way or not” (p. 153)? Is that comforting or discomforting, and why?

4. At the end of the chapter, Taylor tells the story of how she refrained from taking Communion one time because it was painful to her Jewish companion (pp. 157–59). She asks, “Am I really meant to choose between [Jesus] and my neighbors of other faiths?” What do you think of her decision in that instance? What does it mean to you to love your neighbors of other faiths?

Responses to Week 5 Questions

Chapter 7: “The Shadow-Bearers”

1. On page 129, Taylor says that September 11 changed the way Americans view Islam, resulting in what President Bush called “a quiet, unyielding anger” (p.129), that continues today. What fears do you have around terrorism? Where do they come from? How do they affect your perception of everyday Muslims?

I don’t fear terrorists or terrorism; what disturbs me more are the xenophobic behaviors and statements from white nationalists that give rise to it – especially when they come from the current President of the United States. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” and “America First” tropes continue to undermine any rational foreign policy and have only fueled the fires of racism and empowered nativist ideologies like white separatism and ethnonationalism (i.e., that nations should be defined by a shared heritage, a common language, a common faith, and a common ethnic ancestry). Such language are veiled attempts to push back against the reality of globalism – that all people matter, wherever they live, and that universal freedom and human rights should and can be fostered for all of humanity, not just for the privileged few.

So, contrary to ultra-nationalistic examples of xenophobia, my “perception of everyday Muslims” has led me to reach out in friendship, not only toward them, but all other persecuted minorities within our community. They are the ones being terrorized, not me.

2. Referencing author Jonathan Sacks, Taylor identifies “groupishness” as the source of our violence, more than religion or secularism (p.131). Where do you see “groupishness” in your own community? How can we maintain a positive sense of group identity without needing to diminish the value of those who do not belong to it?

“Groupishness” seems like just another term for tribalism to me and, taken to its extreme, will always lead to bigotry, racism, and acts of violence – terrorism and war being only two examples. Collectively, we need to expand our social networks to include others different from us – not exclude, ostracize or otherwise eliminate them. For far, far too long we’ve associated difference with dangerousness and so labeled those “others” (i.e., not like us) as savages needing either reformation or banishment, conversion to our ways of thinking or even extinction as a people (e.g., שואה or Sho’ah – the Hebrew word meaning “catastrophe” that most devout Jews use instead of the word Holocaust which literally means “burnt offering”). Consider our own nation’s dark history in its treatment of ethnic, racial and religious minorities. Ultimately, our differences should not only be understood, but celebrated! They should foster real dialogue, not the kinds of endlessly vitriolic “us” vs. “them” debates that inevitably lead to “winners” and “losers” and so have deepened our separations from each other.

Chapter 8: “Failing Christianity”

1. Have you ever looked at your faith from the outside, as Taylor did, through the eyes of historians and religion scholars? What has that lens revealed to you?

Yes, I have – beginning with my master’s degree in theology from Duke University, followed by many years of deep conversations with colleagues and religious scholars of other faiths and including a certification in spiritual direction with a focus in interspirituality. It was my associate membership in the Westar Institute (a.k.a. the “Jesus Seminar”), however, that literally saved and then reinvigorated my commitment to the ordained ministry after struggling so many years against the doctrines, dogma and orthodoxies of the institutional Church.

To some extent, my responses to question #2 of Chapter 5 (above) answer what the bifocal “lens” of scholarship and theological dialogue has revealed to me. I’m still using those kinds of “lenses.”

Some years ago, in an NPR program entitled “Teaching Children to Ask the Big Questions Without Religion,” the most significant statement made there, in my opinion, was that “it's a sacred space to explore not knowing.” All too often, we in the religious community have claimed that we have all of the answers. We do not. So, neither does our Bible nor any other version of holy scripture, neither did Jesus nor any of the other great prophets of history. Tragically, we also have given many patently wrong answers as we’ve searched for meaning (e.g., most egregiously, the doctrine of original sin). Christianity – much like its parent, Judaism – has offered what it believes to be “true” from its own cultural and historical perspective. But much truth lies elsewhere and beyond. In the end, doubt just has to be part of any valid religion. Ask yourself, “How do I know what I know?” We’ve got to have the courage and integrity to say that – in many ways and about many things – we simply do not know. It’s from there that all really profound spiritual journeys begin. We’ve got to teach this truth well to our children and our grandchildren – but, first, we’d better learn it ourselves.

2. Taylor describes learning from people of other faiths about “how bruised they were by Christian evangelism,” especially since their consensus was that “Christian evangelists are not very good listeners” (p.148).

• What is your experience of Christian evangelists?

For the most part, my experiences have been simply witnessing outrageous televangelists like Jim & Tammy Faye Bakker (on their “Praise the Lord Television Network”), Joyce Meyer (and her “Word of Faith” movement), Jimmy Swaggart (and his staged weepy confession of sin), Robert Tilton (who says “poverty is the result of sin”) or Jesse Duplantis (who insisted that his followers had to buy him a private jet) – and the shallow, self-centered theology and shady financial shenanigans of them all. What’s worse, many of these charlatans are still around peddling their nonsense and taking advantage of vulnerable and ignorant people. If it weren’t so destructive, it’d be laughable.

Regrettably, the word “evangelist” has been corrupted by such people. It should retain at least something of its positive roots (from the Greek, εὐαγγέλιον or euangélion meaning “good news”) – someone who shares good news – in this case “of God.” Supposedly, it’s what we Christians have experienced in the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. But there’s very little good news in the messages of these televangelists. Their teachings and behavior are unconscionable.

In the few times that one of those itinerant evangelists has come to my front door, just learning that I was a well-educated clergyman who would clearly, but gently, attempt to debunk their theology, meant that they usually didn’t hang around very long. Most of them usually left without so much as a “God bless you.”

• Have you ever witnessed Christian evangelism done in a way that seemed respectful to others and their faiths?

Yes, I have. It’s often happened to me in the midst of interfaith gatherings in which no one is there to proselytize or condemn the theology of others in attendance. We’re there to discover, embrace and celebrate what we hold in common while remaining open to what we might learn from one another. That’s good news.

• Who do you think is the best judge of whether evangelism is respectful or not?

The one on the receiving end. If it truly is “good news” and makes sense to that person, then it just might be, not only “respectful,” but actually well-founded.

3. What do you think of Taylor’s idea that “Jesus alone is the arbiter of salvation in his name” and that his saying about being the way, the truth, and the life “puts him in charge of deciding who is on his way or not” (p.153)? Is that comforting or discomforting, and why?

I don’t believe that Jesus of Nazareth would ever have seen himself as the final “arbiter” of salvation nor would he have ever claimed to be. Taylor clearly says that “Christians do not have sole custody of the only way to God” (p.152). She gets it. As she writes at the end of the paragraph just before:

“The way to make a disciple is to be one. If your life does not speak,

your footnotes will have limited impact. Become worthy of the message…” (loc. cit.).

So, when The Gospel According to John puts such words as these “I am…” sayings in the mouth of Jesus, I think something very important got lost in the translation. What he must’ve meant was something like this:

“Do as I do. Show compassion for all who cross your path as I have. Walk,

then, in this way alongside me. Discover, for yourselves, the fullness of that life

that I’m attempting to clarify for you and is within the best teachings of our faith.”

– and that faith (i.e., his religion) of course, was Judaism.

4. At the end of the chapter, Taylor tells the story of how she refrained from taking Communion one time because it was painful to her Jewish companion (pp.157-159). She asks, “Am I really meant to choose between [Jesus] and my neighbors of other faiths?” What do you think of her decision in that instance? What does it mean to you to love your neighbors of other faiths?

I think that she was simply feeling a moment of compassion for, as well as solidarity with, her colleague – out of love and respect, nothing more. The memory of family lost in the Sho’ah was too poignant for the rabbi to join in the symbolism of communion – especially with that anti-Semitic association “His blood be upon us and on our children” (Matthew 27: 25). And Taylor wasn’t “choosing” Jesus over her companion in that moment; I see her question as more rhetorical – she’s demonstrating that she knows better than that.

Her quote from Jonathan Sacks at the close notes, “Peace involves a profound crisis of identity.” As is the nature of every crisis, it presents any number of choices between danger and opportunity. Let's make an informed choice. So, I agree with Taylor’s closing comment: “In my case, it also involved finding a new way to follow Jesus, even if that meant leaving the marked path” (p.159). I have chosen to do the same as well.

To me, loving my “neighbors of other faiths” must mean at least showing just such compassion as this, while continuing to seek understanding, cherishing what we have in common, and standing in solidarity with others whenever they’re under attack or feeling excluded simply because of their faith or ethnicity.

Week 4 Questions

CHAPTER 5: THE NEAREST NEIGHBORS

1. A Jewish psychiatrist writes Taylor about the latent

“language of contempt” he has found in her writing

(p. 87), in which she reinforces the idea that God’s

covenant with Abraham has been supplanted by a new

covenant with Christ. Is that idea new or old to you?

How might a compelling challenge to that idea change

your reading of the New Testament?

2. Taylor contrasts the Christian emphasis on right re-

ligious belief with the Jewish emphasis on right reli-

gious practice. What is your answer to the question on

page 95, “How does being Christian change the way

you live?” If “Christian” does not describe you, choose

another word that does, such as “Buddhist,” “Human-

ist” or “Spiritual but not Religious.”

CHAPTER 6: DISOWNING GOD

1. As Taylor speaks to a broader audience on religious

issues, some questions come to the fore. Read the ques-

tions on pages 102 to 103. Which is most urgent for you

to answer, and why?

2. Taylor persists in reading the Bible because “it is my

baseline in matters of faith—something far older than

I am, with a great deal more experience in what it

means to be both human and divine. . . . I return to the

Book—not to find a solution, but to remember how

many possibilities there are” (p. 106). How do you ap-

proach the sacred text of your tradition? How has your

approach changed, and—if you still read it—why do

you persist?

3. Taylor recounts some stories of religious strangers in

the Bible—from King Melchizedek in Genesis to the

wise magi of the Gospels—who enter the sacred story

of a particular tradition in order to deliver a blessing

and then leave it again without ever becoming a mem-

ber of the tradition (pp. 108–110). What do you think

of that idea? How does it challenge common under-

standings of how God works?

4. What is your response to Taylor’s interpretation from

Jesus’s first sermon at Nazareth (pp. 111–17)—that no

tradition has privileged access to the divine and no reli-

gion owns God? How would accepting this conclusion

change how you practice your faith or how you relate to

other faiths?

Responses to Week 4 Questions

Chapter 5: “The Nearest Neighbors”

1. A Jewish psychiatrist writes Taylor about the latest “language of contempt” he has found in her writing (p.87), in which she reinforces the idea that God’s covenant with Abraham has been supplanted by a new covenant with Christ. Is that idea new or old to you? How might a compelling challenge to that idea change your reading of the New Testament?

As it’s been expressed in Christian fundamentalist orthodoxy, that’s old news. Very early on in my faith journey, the compelling challenge that I experienced began with my recognition that the Bible was not written as history – it was mostly myth and legend and held widely varying points of view. Much of it you just cannot take as scientific fact. So – while not quite rejecting both views on the nature of the covenant – it has led me to understand, first, that they both present archaic images of God representative of the cultures of that era (so, I find them questionable – they’re certainly not mine), and yet, second, both still remain helpful toward our ever-evolving understandings of the nature of the Sacred in our midst as well as in the greater universe of which we’re all such an infinitesimal part.

To Taylor’s credit, she recognizes how her use of such Christian orthodoxy was, indeed, perpetuating the centuries-old Jewish/Christian schism that has for far too long stifled what might have been honest and true dialogue between these two expressions of faith. As she, quite rightly, notes:

“So much of the New Testament was written by people at odds with the

Judaism of their time that their anti-Judaism was baked into the gospel” (p.88)

In the good words from Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (whose book Not In God’s Name I hope will be our next study!), “moral and spiritual dignity extend far beyond the boundaries of any one civilization” (p.89) – and, I would add, far beyond any one religion. While this anthropomorphic and exclusive imagery for God has been rejected by many biblical scholars, both Judaism and Christianity still have added immeasurably to the ways we’ve come to understand the nature of the Sacred and the ways in which they continue to call us to live out our lives.

2. Taylor contrasts the Christian emphasis on right religious belief with the Jewish emphasis on right religious practice. What is your answer to the question on page 95: “How does being Christian change the way you live?” If “Christian” does not describe you, choose another word that does, such as “Buddhist,” “Humanist” or “Spiritual but not Religious.”

I have to admit, this question suddenly stopped me. According to the key doctrines and orthodox teachings of Christianity concerning Jesus of Nazareth – how and why he was born, lived, died, and was resurrected – I cannot consider myself to be a Christian (let alone Methodist – United or not). And yet I was raised in the bosom of the Church: I was baptized by my maternal grandfather when I was twelve years old, became president of our church’s youth fellowship when I was a teenager, attended church worship services “religiously” throughout my childhood and for most of my adult life, then spent three years in seminary as a candidate for the ordained ministry in The United Methodist Church, was ordained, and served as a pastoral leader in that denomination for over thirty years. Throughout all of those years, however – from the beginning until now – I chafed against the positions of Christian orthodoxy and sought to reform the Church. How’s that for monumental presumptuousness? I was even accused and brought to trial by my own denomination for my heretical behavior. And yet I’ve hung around, still in love with this Jesus who, I was assured as a child, loved me. Am I a Christian? You tell me. Several of my own colleagues say that I am not.

Curiously enough, I would wholeheartedly agree with all of the fundamental affirmations that are promoted by the Unitarian Universalist Association:

• the inherent worth and dignity of every person

• justice, equity and compassion in human relations

• acceptance of one another and encouragement of spiritual growth within a congregation

• a free and responsible search for truth and meaning

• the right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within this congregation as well as in society at large

• the goal of world community with peace, liberty and justice for all

• respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part

Does that, then, make me a Unitarian Universalist – who, many would say, isn’t a Christian denomination?

While I remain firmly grounded in my Christian roots, I suppose the term “interreligious” comes close to where I now am – deeply appreciative of the ongoing dialogue among all of the major religions of the world. I would go a step further to explain that I practice what has been called “interspirituality.” I think Wayne Teasdale (author of The Mystic Heart) was the one who actually first coined that term to describe this perspective. As I understand it, it assumes that beneath the diversity of theological beliefs, rites, and observances, lies a deeper unity of experience that is humanity’s shared spiritual heritage. Actually, I’d say that a mystical approach to spirituality is, most likely, the origin of all the world’s religions. Those of us who do embrace interspirituality have become convinced that every authentic spiritual path offers unique perspectives and rich insights into deeper, even direct, experiences of truth. In our own time, the wisdom and depth of all such paths as this are available to anyone who will bring an open mind and heart – as well as a generous spirit of his or her own – to this kind of a search across religious traditions. I think that all authentic spiritual paths, then – at their mystical core – are committed to the common values of human community, peace, compassionate service, and love for creation. An inner life awakened to the powers of love and responsibility will just naturally express itself through that kind of engaged spirituality. In Teasdale’s words, authentic spirituality can lead us all to the kinds of “acts of compassion…contributing to the transformation of the world and the building of a nonviolent, peace-loving culture that includes everyone.” I want to continue to be part of that transformation.

All of that being said, I resist the simplistic conclusion that the religion that arose from Jesus of Nazareth – Christianity – is more about “right religious belief” than it is “right religious practice.” It’s both – or it surely should be. As much as anything, I’m trying to follow in the footsteps of Jesus – and he, I frequently remind everyone, was not a Christian and remained to be Jewish to the core.

Chapter 6: “Disowning God”

1. As Taylor speaks to a broader audience on religious issues, some questions come to the fore. Which of these questions is most urgent for you to answer, and why?

• What does it mean to be a person of faith in a world of many faiths”

Of these five questions, I’d say this first one seems “most urgent” to me, principally because of all of the harm that continues to be done to people in the name of religion – and I don’t necessarily mean the harm done by religiously motivated terrorism alone. It must include the ways in which people continue to be shamed, shunned, excommunicated, and worse, simply because they’re different or don’t measure up to the expectancies of some religious orthodoxy. To “be a person of faith in a world of many faiths” must at least mean that we see others as worthy of respect and equality – whoever and wherever they are.

2. Taylor persists in reading the Bible because “it is my baseline in matters of faith – something far older than I am, with a great deal more experience in what it means to be both human and divine…. I return to the Book – not to find a solution, but to remember how many possibilities there are” (p.106). How do you approach the sacred text of your tradition? How has your approach changed, and – if you still read it – why do you persist?

I continue to turn to the Bible as I always have: as a library of 66 very different texts that reveal an ancient culture’s experience of God – including, but not limited to, the life, teachings and parables of Jesus of Nazareth and the ways in which his early followers interpreted them. While I first understood this Jesus as foundational for my faith, I’ve since learned to embrace the contributions of others who’ve sought to do the same thing – before and after him. So, while the Bible remains to be very important to me, I don’t see it as the one-and-only revelation of the Sacred. I persist – with this Bible but other sacred texts as well – because I’m fascinated by this revelation of the Sacred wherever it happens, through whoever speaks of it, and however it continues to happen. I always have.

3. Taylor recounts some stories of religious strangers in the Bible – from King Melchizedek in Genesis to the wise magi of the Gospels – who enter the sacred story of a particular tradition in order to deliver a blessing and then leave it again without ever becoming a member of the tradition (pp.108-110). What do you think of that idea? How does it challenge common understandings of how God works?

These so-called “righteous gentiles” are simply examples of how experiences of the Sacred are not limited to any one religion, culture or people – we have this in common as a species. I think that’s why the English hymnodist, William Cowper, would write in 1773: “God moves in a mysterious way / His wonders to perform / He plants His footsteps in the sea / And rides upon the storm….” That very anthropomorphic and paternalistic imagery aside, before it became a hymn it was a poem entitled “Light Shining out of Darkness.” It’s significant, I think, that this poem – the last hymn text that Cowper ever wrote – was written just before the onset of a depressive illness during which he attempted suicide. It was set in juxtaposition to a statement – attributed to Jesus – that Cowper chose from the Gospel According to John: “Jesus replied, ‘You do not realize now what I am doing, but later you will understand’” (13: 7). Cowper’s interpretation of that, I think, is heard in his first line, encouraging us to trust in the greater wisdom of the Sacred in the face of terrible trouble or inexplicable events.

Never mind what the Bible or Cowper or other philosophers and theologians have to say about this, the challenge as to understanding “how God works” remains a deep mystery to me – especially in the face of real evil and inexplicable tragedy. There’s an entire branch of theology – called theodicy – that’s devoted to such a conundrum which asks this straightforward question: “If God is a god of love, then why is there evil?” It’s a good question. I know how I answer it (at least partially, in my response to question #3 of Chapter 4 above.). How about you?

4. What is your response to Taylor’s interpretation from Jesus’s first sermon at Nazareth (pp.111-117) – that no tradition has privileged access to the divine and no religion owns God? How would accepting this conclusion change how you practice your faith or how you relate to other faiths?

I would agree with the conclusion “that no tradition has privileged access to the divine and no religion owns God.” It seems absurd to think otherwise; I came to that same conclusion half-of-a-lifetime ago. However, I’ve learned to practice my faith in relationship to others with a good deal of humility and open-mindedness (Even if a colleague once said to me, “But being openminded doesn’t mean being empty-headed” – as if that was what I was doing.). When it comes to theology and the practice of my ministry over these past forty years, I’ve embraced what seems and feels right to me (read that as the ongoing dialogue between my “head” and my “heart”), even though it remains to be, yes, decidedly unorthodox and heretical to some.

So, even though I wouldn’t use Taylor’s traditionally anthropomorphic imagery for God, I would agree with her premise when she says: “Whatever is holding people down, God means to lift up. Whatever is tearing people apart, God means to mend” (p.114). Amen to that. Let’s join in the effort, shall we?

Week 3 Questions

CHAPTER 3: WAVE NOT OCEAN

1. Try this exercise with your group: Write on an index

card what you mean when you say “God” without sign-

ing your name. Then gather all the cards and take turns

reading them aloud. Talk about the similarities and dif-

ferences you hear and what they say about your various

faith traditions (p. 45).

2. Taylor quotes author Paul Knitter, who wrote, “The

more deeply one sinks into one’s own religious truth,

the more broadly one can appreciate and learn from

other truths” (p. 48). Can you describe any instances

where you’ve had this experience in your own life? How

has maturing in your own faith helped you to appreci-

ate other faiths?

CHAPTER 4: HOLY ENVY

1. There were at least three obvious routes of action Taylor

could have taken when finding other religions attractive:

convert to one of them, make a quilt of spiritual bits and

pieces from all of them with none at the center, or let her

attraction to other teachings transform her love for her

own (pp. 63–64). She chooses the third as the best op-

tion for her. Do you know anyone who has chosen one

of the others? What choice sounds best to you?

2. What parts of other religious traditions do you envy?

How could that envy be turned into what Taylor de-

scribes as “holy envy” (an appreciation of other reli-

gions that deepens one’s own)?

3. Taylor laments the Christian doctrine of original sin,

saying, “It drops the bar on being human so low that

you have to wonder why we don’t all just stay in bed”

(p. 74). At the same time, many Christians embrace this

doctrine because it makes clear that humans cannot

work their way to salvation, but must accept salvation

as a gift of sheer grace. How important is original sin to

your understanding of faith?

4. Rather than see religions as competing for the one and

only place of truth, Taylor presents a view where “absolute

truth moves to the center of the system, leaving people of

good faith with meaningful perceptions of that truth from

their own orbits” (p. 78). She also shares the metaphor

of religions as different rivers having the same heavenly

source. How do you respond to these images and why?

Responses to Week 3

Chapter 3: “Wave Not Ocean”

1. What do you mean when you say “God”? What are the similarities and differences that you hear from others and what do they say about your various faith traditions (p.45)?

Much of that concept continues to be a deep Mystery to me – and I’ve been studying theological issues for the majority of my teen-age and adult life. I must confess that I’ve become an agnostic when it comes to the traditional understandings of God – and I completely reject the paternalistic and judgmental deity that is all too often presented in the Bible and, for centuries now, has been promulgated by the Church.

However, for purposes of answering this question, the settled concept to which I’m closest has been called panentheism (also known as monistic monotheism – i.e., a single godlike substance). To be clear, it’s not pantheism which claims that God is synonymous with the material universe and interpenetrates every part of nature – much like the soul of the universe or a universal spirit which is present everywhere but at the same time transcends all of creation. The word panentheism can literally be translated as “all in God” (from the Greek πᾶν or pân, meaning "all", ἐν or en, meaning "in" and Θεός orTheós, meaning "God"). I understand that to mean that there’s a Creative Energy behind all that exists in the universe and we can either be in harmony or in conflict with it (as in our penchant for violence, our effect on climate change, or our outright destruction of nature). The harmonious way of being leads to shalom (healing, wholeness, well-being…peace); the latter leads to insufficiency, destruction and chaos.

Notice, in all of this, I’ve not found anything like a sentient being with whom we can be in conversation in the same ways that we converse with other human beings. For that reason, I find petitionary or intercessory prayer deeply problematic. Oddly enough, however, I can feel a prayerful thankfulness and be moved to praise or adoration before evidence of this Creative Energy which suffuses all that I believe to be good and blessed about being alive in this still expanding universe.

I hear similarities within our Lutz book group as they’ve spoken of God as “love” or as the kind of spiritual intuition or contemplative ecstasy that comes from mystical experiences – and, yes, I even see a kind of “divinity” revealed within the systematic knowledge that comes to us through science (Thanks for continuing to remind us, Peter – but you’re going to have to explain “chaos theory” to me some time!). My concept of God embraces all of these revelations – and (much like our author) I still have room for more. To paraphrase, yet again, Paul’s quote from that ancient hymn in his first letter to the church at Corinth: “Now we see only a reflection – an image as if looking through darkened glass – and yet face-to-face. We only know in part; maybe, one day, we shall fully know as we are fully known” (1 Corinthians 13: 12). So, I say we’ve a lot more to discover about this Mysterious, yet Sacred, phenomenon.

2. Taylor quotes author Paul Knitter, who wrote, “The more deeply one sinks into one’s own religious truth, the more broadly one can appreciate and learn from other truths” (p.48).

• Can you describe any instances where you’ve had this experience in your own life?

I do think that what Knitter says here is true. Just one page before, Taylor speaks to an aspect of Buddhism that I’ve come to affirm, myself, in place of the doctrine of original sin:

“The things that happen to us are the natural consequences of our actions,

and no one can relieve us of them. If we do not like what is happening, it is

up to us to change. No one is watching over us to punish or reward us.

Enlightenment is its own reward, the peace that passes all understanding” (p.47).

Christianity has become so obsessed with sin. As Taylor points out, Buddhism “says the problem is ignorance” (p.48). So, yes, “None of us knows we have ‘a worldview’ until we see the world from a new angle” (p.49).

I find that I’ve also been helped, immensely, by the Unitarian Universalist tradition. The one that sticks with me the most is that tradition’s understanding of sin. Universalists say that sin is like an illness; it should be healed, not punished. So, that’s their understanding of salvation – healing ourselves and the world by living a life that’s not self-centered, but is patterned on lovingkindness and compassion. Curiously enough, I think that’s very close to the Buddhist understanding of enlightenment. In the end, it’s not miracles or magic that matters; it’s what a person has been taught and how he or she has lived life that makes all the difference in the world.

• How has maturing in your own faith helped you to appreciate other faiths?

It’s helped me see how all religions have evolved – for good or ill. Our task is to pay attention and to question everything (particularly dogma but also much, so-called, doctrine). Again, that’s how I understand the word “heresy” (from the Greek, αἵρεσις or hairesis meaning “a choice” or “opinion”) – it’s my right to choose. It’s the Church that has changed the meaning of heresy to be “a wrong belief.” So, I am not only content to be considered a heretic, I demand my right to choose what I believe and what I do not believe. Throughout it all, however, it must be an attempt to discover the truth and leave pure fiction behind.

I would still say, though, that all of the major religions of the world hold kernels of truth; but it’s up to us to discern which those are in the pursuit of Ultimate Truth. As Taylor explains the Buddhist way, “Walk the way for a while and decide for yourself what is true” (p.55).

I particularly like the author’s interpretation of what our own prophet, Jesus of Nazareth, implied:

“If someone wants to learn more about God,…it will involve more than believing

someone else’s answers. It will involve thinking deeply about the questions

you are asking and why. Then it will involve acting on the answers you come

up with in order to discover what is true” (p.57).

Chapter 4: “Holy Envy”

1. There were at least obvious routes of action Taylor could’ve taken when finding other religions attractive: convert to one of them, make a quilt of spiritual bits and pieces from all of them with none at the center, or let her attraction to other teachings transform her love for her own (pp.63-64). She chooses the third as the best option for her. Do you know anyone who has chosen one of the others? What choice sounds best to you?