This Book Study will begin February 5, 2017

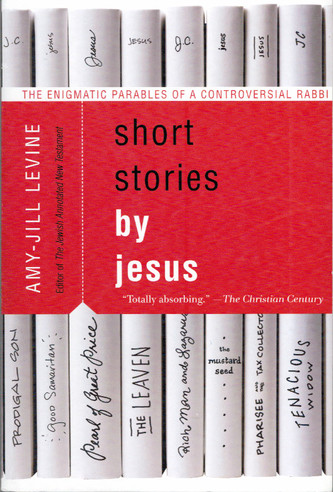

The renowned biblical scholar, author of The Misunderstood Jew, and general editor for The Jewish Annotated New Testament interweaves history and spiritual analysis to explore Jesus’ most popular teaching parables, exposing their misinterpretations and making them lively and relevant for modern readers.

Jesus was a skilled storyteller and perceptive teacher who used parables from everyday life to effectively convey his message and meaning. Life in first-century Palestine was very different from our world today, and many traditional interpretations of Jesus’ stories ignore this disparity and have often allowed anti-Semitism and misogyny to color their perspectives.

In this wise, entertaining, and educational book, Amy-Jill Levine offers a fresh, timely reinterpretation of Jesus’ narratives. In Short Stories by Jesus, she analyzes these “problems with parables,” taking readers back in time to understand how their original Jewish audience understood them. Levine reveals the parables’ connections to first-century economic and agricultural life, social customs and morality, Jewish scriptures and Roman culture. With this revitalized understanding, she interprets these moving stories for the contemporary reader, showing how the parables are not just about Jesus, but are also about us—and when read rightly, still challenge and provoke us two thousand years later.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Week 9 Questions

The Rich Man and Lazarus

1 – Why do you think this is or is not a story about the afterlife? 268

2 – How do you understand “Sell all that you have and distribute the money to the poor...”? 273

3 – Where are the good places to beg? 279

4 – How would you characterize Abraham? OR What kind of thing is Abraham? 283

5 – Does this sound like a Jesus parable to you? Why? 285

6 – How does this story relate to your ideas of what happens after your death? 294

7 – In some “stories” our author spent considerable time discussing the catch, hook, or barb the story might have for Jesus’ audience. Where is that issue for this story? 296

Conclusion

8 – If you were to compose a parable, to what would you compare the Kingdom of God? 298

9 – Which story do you like best ( for you )? Why? 302

Responses to Week 9 Questions

Week 9 Questions

The Rich Man and Lazarus

1. Why do you think this is or is not a story about the afterlife? [p.268]

Historically, the Pharisees were thought to have believed in some form of the resurrection of the dead, while the Sadducees did not. But many Jews at the time of Jesus (maybe even Jesus himself?) believed that they would be punished or rewarded after death for the ways in which they had lived their lives – even though there never was any clear teaching about heaven itself. So, I see no reason why this story should not be a story of just what it speaks about: speculation on what will happen to people in the afterlife based upon how they lived in this life. In that, I’d agree with Levine that this is “probably what the majority of the original auditors of the parable…thought as well” (p. 271).

2. How do you understand “Sell all that you have and distribute the money to the poor...”? [p.273]

It’s another way of saying, “Get rid of the single impediment in your life that stands in your way to becoming a truly compassionate human being – and that’s probably your most precious possession.” In this particular story, the rich man is very rich; so, it’s that very wealth that’s consuming him and keeping him from leading a life of justice and compassion. As it’s been said in another way, “Either you worship God or you worship something that you’ve made your god.” For the rich man his wealth has become his god.

3. Where are the good places to beg? [p.279]

Wherever it is that you will receive the assistance that meets your need. It could be anywhere, but to be most effective it should be in those places and among those people where your very need to beg could be transformed into circumstances in which you no longer are dependent upon such handouts. In other words, you then are able to take charge of your own life and will no longer need to beg.

4. How would you characterize Abraham? OR What kind of thing is Abraham? [p.283]

I think Jesus’s connection to the biblical Abraham is deliberate. As Levine points out, “the reference to Abraham…suggests several roles: father figure, protector, symbol of hospitality, eschatological judge, and more.” This “image would have been a familiar one” to those who would hear this parable. Also, “Unlike the rich man, Abraham welcomed strangers to dine with him (Gen. 18: 1-15).” What’s more, “Abraham was also known as having access to heavenly knowledge and associated with the afterlife…4 Maccabees 7.19 (also 16.25).” So, I would agree with Levine’s conclusion: “Some Jews may have thought that Abraham would plead for them all; Jesus thought otherwise” (p.284).

5. Does this sound like a Jesus parable to you? Why? [p.285]

That’s difficult to say, one way or the other. I’d agree with the Jesus Seminar – that voted vv. 19-26 of this one gray, and vv. 27-31 black – that at least the final line is a Lucan emendation critical of the Jewish lack of belief in the resurrection of Jesus. Luke is often contrasting the blessedness of the poor with the condemnation of the rich (e.g., 6: 20, 24). Moreover, this parable is the only one in which a character is given a proper name – something Jesus usually didn’t do. Finally, this theme of the afterlife was widespread in folk tales in the ANE. Luke’s, more than likely, just taken one of those common stories and reshaped it into this parable. On the other hand, unlike the common folktales of the afterlife, this story doesn’t have a judgement scene; the fates of the characters are simply reversed. In that sense, it is similar to other parables of reversal that we assume were told by Jesus (cf. “The Laborers in the Vineyard” and “The Great Banquet” (cf. Luke 14: 15-24 and “The Wedding Feast” in Matthew 22: 1-14). So, we can’t be certain of the origin of this parable.

6. How does this story relate to your ideas of what happens after your death? [p.294]

I can’t say because I truly have no idea what will happen after my death – not even a half-formed image based upon wishful thinking. While I’d like to think that some part of me – my soul or spirit – will continue to exist somehow, somewhere, I doubt it will be so because I have no evidence that it has ever happened to anyone.

7. In some “stories” our author spent considerable time discussing the catch, hook, or barb the story might have for Jesus’ audience. Where is that issue for this story? [p.296]

I suppose that it’s as it becomes clear that you can’t go back and live your life over again. You’ve got one chance to get it right, so don’t waste it. Clearly, those who would hear this parable will know what’s being asked of them. As Levine points out, “Once they are dead, they will not get a second chance; there is no postmortem do-over” (p.293).

Conclusion

8. If you were to compose a parable, to what would you compare the Kingdom of God? [p.298]

My first thought is to compare the “Kingdom of God” to being part of a healthy and loving family, a family in which everyone is an integral part – i.e., neither the family nor each member is complete without the other. This family, for me, would exemplify in the fullest sense the meaning of the Hebrew word shalom: a reality in which wholeness, well-being, health, self-actualization, and peace all are fully realized.

9. Which story do you like best (for you)? Why? [p.302]

It’s come as somewhat of a surprise to me that I find myself drawn to the one parable that seemed to give so many of us trouble: “The Widow and the Unjust Judge.” I suppose that this has happened because of recent events (both here at home and in the larger world) – events at which justice will only be received when people demand it. It’s the polar opposite of apathy. It’s deliberate – if often aggressive – persistence in the face of injustice until justice, finally, is done. This has become more important to me, now, than it ever has before.

Oddly enough, however, this is much like the conclusion to which I came about hearing, yet again, about “The Pearl of Great Price.” The “Kingdom of God/Heaven” may just be a way of living in the world. It’s an action and not a commodity to be bargained over; it’s not even a person to emulate or follow (e.g., Jesus, et al.). Just what that action is may only be known for each of us in and through our own experiences of life. But we will know its value the moment we recognize how much it means to us. It’s what brings us to that moment of decision when we say to ourselves, “This is what I must do.”

Week 8 Questions

The Widow and the Judge

1 – What were your feelings about the widow immediately after reading the parable (before our author has a chance to “help” you understand)? 241

2 – Which character do you identify with? Why? 243

3 – How would you compare this widow’s condition with today’s widows? 247

4 – How do you feel about judges, professionally and personally? 252

5 – How do you understand vengeance in this story? 254

6 – Will you resist or rescue this story? How and Why? 262

7 – Does making the judge a conservative republican and the widow a liberal democrat work for you? How about the reverse? 263

8 – Is vengeance ever justice? Explain. 265

9 – Notice that “The Kingdom of God is like...” does NOT appear here. After this parable, what do you think is the “right question”? 265

Responses to Week 8 Questions about The Widow and the Judge

The Widow and the Judge

1. What were your feelings about the widow immediately after reading the parable (before our author has a chance to “help” you understand)? [p.241]

It’s a bit difficult to “erase” a significant portion of my adult lifetime during which I’ve grappled with this parable (even before my years at seminary and getting the “spin” from my professor of Koine Greek that “every translation is an interpretation”). As best as I can recall, though, my first impression of this parable attributed to Jesus came from its opening line: persist in your prayers and don’t become discouraged if you don’t get the answer that you’re looking for; God will provide it – eventually. If someone as typically powerless in the ancient near east as a poor widow will find justice, so will you – if you’ll just keep at it.

2. Which character do you identify with? Why? [p.243]

Unfortunately (?), I identify with the judge. All too often I’ve given in to those who complain or push the loudest just to shut them up – even if it’s to redirect them to someone else because I don’t want to deal with them. This is as true with persistent grandchildren as it may have been with pushy church members. Let somebody else deal with this pain-in-the-neck! I’ve got better things to do. Or so I have rationalized.

3. How would you compare this widow’s condition with today’s widows? [p.247]

Widows, today, probably have more safeguards to protect their vulnerability than did the widows who lived in the time of Jesus – principally because women can compete with men for positions in the job market in ways that they could not in the ANE (Ancient Near East). Women still face the injustice and inequality of the “glass ceiling” and its related entrenched patriarchy, but not as much as their gender once did. Even so, widows today may have as many reasons to seek justice in a court of law as the widows of the 1st century CE surely did.

4. How do you feel about judges, professionally and personally? [p.252]

Since I’ve personally known a very good one in Don Fretz, and have witnessed the depth of judicial excellence represented by the majority of the members of the Supreme Court of the United States, my feelings (for the most part) are positive. I’ve had no professional dealings with the secular judicial system so, in that regard, have nothing of substance to say about the judges within that system. However, I have felt the judgment of my peers within the ecclesiastical judicial system. I was brought up on charges of disobeying The Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church for participating/presiding over a “Holy Union” between two lesbians (back then they weren’t legally able to “be married” even outside the Church). I thought that the laws of the Church, then as now, were unjust; so, I disobeyed and challenged them. For a number of reasons, our case was dismissed without ever really being adjudicated. So, the conundrum within our denomination remains. But now we have a married lesbian bishop (in Karen Oliveto), so it should be interesting, to say the least, to see what happens next.

5. How do you understand vengeance in this story? [p.254]

Levine says that “we do not know, finally, how to judge our judge” (p.252). Neither can we say much about the intentions of the widow in our parable. Was she really out for vengeance (as Levine claims), that she “is nor moral exemplar” (p.253) and to “‘grant her justice’ literally means ‘avenge her’” (p.254)? A further translation of that Greek word, ekdikeo could just as legitimately be “vindicate her” which could mean that she’s just looking to be cleared from some accusation, to be absolved, and to have any associated guilt disproved. I’m not as convinced as Levine is, then, when she claims “The judge…is co-opted by and so complicit in the widow’s schemes. When he accedes to her request, he facilitates her vengeance.” Maybe she only does want justice.

6. Will you resist or rescue this story? How and Why? [p.262]

I think that I’m doing both. I’m resisting Levine’s conclusion that the widow’s persistence is based upon a burning desire for revenge. And I’m “rescuing” the widow in the sense that I’m honoring her reason(s) for persistence. I disagree, then, with Levine’s conclusion that both the widow and the judge “become complicit in a plan possibly to take vengeance and certainly not to find reconciliation.” I do agree with Levine saying, “The widow is not ‘weak’…” She may be very clever, conniving even, but vengeful? Show me where else in this brief parable – besides in a single translation of one word – that would bring you to that conclusion? Sure, this persistent woman has gotten under this judge’s skin, but just because she is utterly unyielding in pursuit of justice doesn’t necessarily mean that she’s “out for blood” or “a pound of flesh” from whomever has wronged her. Levine further compounds her negative image of the widow by assuming that she is not only incapable of loving her enemies, but “(capable of being) violent” (p.263). In truth, every human being can do both. And Levine finally nails her position down by bluntly saying: “In the parable, vengeance rules. It is the desire for vengeance that drives the widow…” (p.264). And again: “There is no reconciliation in this parable; there is only revenge” (p.265). I think she has come far too easily to that conclusion.

7. Does making the judge a conservative republican and the widow a liberal democrat work for you? How about the reverse? [p.263]

In a word, no. In fact, introducing partisanship into it changes the parable into something else entirely.

8. Is vengeance ever justice? Explain. [p.265]

No. Revenge is a visceral feeling. Justice is not (and so why we should always strive for rational impartiality). You may feel as if your vengefulness has been fed should you be given justice, but your desire for it should never enter into any just verdict. Revenge is always about retaliation. Justice is (or should be) about restoring balance – hence the image of statues of justice holding a scale in their hands. I believe that the motive of revenge is primarily about expressing rage, hatred and spitefulness; its intention is to do further harm, not bring about true closure or any possibility for reconciliation.

9. Notice that “The Kingdom of God is like...” does NOT appear here. After this parable, what do you think is the “right question”? [p.265]

What might we consider to be things in life that are worth relentlessly pursuing? What ought to command our persistence? I suggest this only because I tend to agree with the Jesus Seminar that this parable has been sandwiched in between two favorite themes of Luke’s: prayer and faithfulness (i.e., vv. 1, 6-8). In this parable, whatever the widow’s request is, it isn’t granted because she’s virtuous. Her cause might not even be just. What’s more, her wish is granted not because the judge is impartial or objective; she simply wears him out. So, again, what might we consider to be worth such persistence given the roadblocks (justified or unjustified) that we will encounter in our own lives?

Week 7 Questions

The Laborers in the Vineyard

1 – What would you like to title the story? Why? 215

2 – What, if anything, has our evangelist, Matthew, done to further an anti-Semitic reading of this story? 217

3 – What difference do you see between landowner and householder? 222

4 – What other descriptions (exchange rates) can you find for a denarius? 224

5 – What were those late hired workers doing before they were hired (here)? “The parable gives no indication that any workers were left out.” 225

6 – What’s the difference between vineyard workers and bakers? 229

7 - “the householder teaches them a lesson by showing them what is ‘right’.” Comments? 230

8 – What happens next week when a different variety of grapes ripen? 235

9 – Can I refuse to sell my house to the black man? “[Or] is it not permitted to me what I wish to do with what is mine?”

Response to Week 7 Questions

The Laborers in the Vineyard

1. What would you like to title the story? Why? [p.215]

I would choose something like “The Master of the House and His Laborers” because the simile compares the kingdom of heaven not to the laborers but to their master (note: oikodespotes literally means “master of the house”) [p.221]. Our focus at least ought to begin there. But I do agree with Levine, however, that titles can be “deceptive; they necessarily focus on one aspect of a story and so deemphasize or mask the importance of others” [p.214]. The parable, though, isn’t as much about the vineyard or the laborers – where they are, who they are, what work they do, or what time of day they do it – as it is about how their master treats them – no matter where or who they are, the amount or type of work they do, or whenever they do it.

2. What, if anything, has our evangelist, Matthew, done to further an anti-Semitic reading of this story? [p.217]

Matthew doesn’t do it; later Christian interpreters have done it (…even John Wesley).

3. What difference do you see between landowner and householder? [p.222]

I see little difference. Now, in the NRSV original translation of oikodespotes as “master of the house,” I think the image is strengthened that this person is someone to be reckoned with – in the sense that he’s “master of all he surveys.” Remember, his actions are the ones that Jesus is comparing to “the kingdom of heaven.” In that it reminds me of a line in William Cowper’s poetical works in which Cowper has his character say, “I am monarch of all I survey, / My right there is none to dispute, / From the centre all round to the sea, / I am lord of the fowl and the brute.” Whether landowner or householder, this person is a person of influence. We should pay attention to not only what he says but what he does.

4. What other descriptions (exchange rates) can you find for a denarius? [p.224]

The “exchange rates” aren’t as important as recognizing that in that day and age a denarius was the going rate for a day’s work, or as Levine puts it, “…a usual wage… that workers would expect to receive.” I discovered that in the ANE (Ancient Near East) it may even have been worth as much as “ten asses.” For our purposes, though, during the early Roman Empire (c. 27 BC) it was not only the daily wage for an unskilled laborer, it was the same for a common soldier in the Roman army. In today’s economy, however, it would be only worth about $28 – hardly a day’s wage.

5. What were those late hired workers doing before they were hired (here)? “The parable gives no indication that any workers were left out.” [p.225]

According to Levine’s interpretation of the Greek, agroi, they were simply “without work.” It doesn’t mean that they weren’t trying to find work (“standing idle” as is the NRSV’s pejorative translation). So, I agree with her observation here that the connotation is that these workers were “wanting work, but not able to find it.”

6. What’s the difference between vineyard workers and bakers? [p.229]

The bakers had a union (“guild” as Levine calls it) that looked out for the rights of everyone in it. The vineyard workers were strictly on their own. What’s more, their work wasn’t piecework – i.e., work paid for according to the amount produced. At least in the context of this parable that’s the arrangement that they all chose to accept from the beginning. As Levine notes, “They are interested in receiving their own payment, not in whether the other workers have enough food.” This seems to be yet another provocation of the parable – i.e., how unlike residents of the “kingdom of heaven” most of us are. All too often we say to others, “I don’t care how you get yours, just stay out of my way as I work to get what’s mine.”

7. “the householder teaches them a lesson by showing them what is ‘right’.” Comments? [p.230]

As Levine points out in her conclusion on the next page (and, I think, rightly so), “The first hired do not want to be treated equally to the last; they want to be treated better.” They’re wrong. Being worthy of acceptance in “the kingdom of heaven” isn’t dependent upon the amount of effort that you put into “achieving” it. It’s not something that you earn – and, more likely, you don’t even deserve it. But like grace itself it’s a free gift given equally to all – even latecomers.

8. What happens next week when a different variety of grapes ripen? [p.235]

It not only makes no difference what “variety of grapes” is harvested, it makes no difference who picks them nor how often or how long it takes to harvest them. The reward is the same: each of us will receive just exactly what he or she needs to make it through the day.

9. Can I refuse to sell my house to the black man? “[Or] is it not permitted to me what I wish to do with what is mine?”

You can. But you’d better not let anyone know that’s the reason for your refusal because it’s against the law. As with the parable, the distinction shouldn’t be about who’s considered “better” but that everyone is considered “equal.” Your comparison here, then (however tongue-in-cheek it may be), is simply a non sequitur.

Week 6 Questions

The Pharisee and the Tax (Toll) Collector

1 – Our last parable, the Mustard Seed, was included in all three synoptic gospels, but this one is only in Luke. Comments? 184

2 – What new thing(s) did you learn from Pharisees: A Brief History? 189-194

3 – Are the Pharisees Democrats while the Sadducees are Republicans? 192

4 – What’s wrong with having “traders in the house of the Lord”? 196

5 - “Women are more naturally good than men are.” Is our author showing her bias? Comments. 202

6 – I do not understand “tithing mint, dill and cumin or even figs. What does this part of the paragraph mean? 203

7 – How do you understand the Tax Collector receiving his justification “on account of the Pharisee”? 209

8 – Will the Tax Collector keep his job? 210

9 – Political: Compare the Tax Collector with modern INS agents. 210

Responses to Week 6 Questions

Week 6 Questions

The Pharisee and the Tax (Toll) Collector

1. Our last parable, the Mustard Seed, was included in all three synoptic gospels, but this one is only in Luke. Comments? [p.184]

I think (as many of the scholars do) that this represents Luke’s biases against Pharisaic Judaism. So, I agree with Levine’s point that “Luke begins the tradition of interpreting the parable in terms of Pharisaic sanctimoniousness and publican saintliness…” [p.186]. While the heart of the parable “may well have been spoken by Jesus” it’s been “contextualized by Luke” [p.187]. In that, I agree with Robert J. Miller’s observation that “Luke’s interpretation of Jesus’ parable…is quite different from how Jesus’ original audience most likely understood it” [p.7, The Fourth R, Vol. 30, No. 1, January-February 2017]. So, “if our aim is to hear what Jesus had to say, we need to do our best to disentangle his story from the interpretive contexts created by the evangelists” [p.8, ibid.] – in this case, Luke himself. Richard Q. Ford also agrees; we need to “work to get past Luke’s anti-Pharisee bias” [p.19, op.cit.].

2. What new thing(s) did you learn from Pharisees: A Brief History? [pp.189-194]

Before being exposed to the scholarship, I too thought that “the majority of Luke’s references to Pharisees are not complimentary” because that’s just how they were traditionally viewed. In fact, as Levine points out here, “For the majority of Jesus’s Jewish audience, the Pharisees would have been respected teachers, those who walked the walk as well as talked the talk” [p.191]. It’s all too easy to forget, as well, that Paul’s own view, as a Pharisee, was that it “was a marker of distinction (Phil. 3.5)” and not one of shame or embarrassment [p.182].

3. Are the Pharisees Democrats while the Sadducees are Republicans? [p.192]

The only similarity might be that in ancient times the Sadducees thought of themselves as “conservatives” because they accepted only the written Law of Moses (the Torah) as authoritative and rejected any subsequent revelation. As a result, they denied many of the doctrines held by the Pharisees (and Jesus, as well, for that matter) – such as the resurrection of the dead, the existence of “angels” and spirits, and the meting out of rewards and punishments after death. Beliefs such as that, the Sadducees thought, were Persian (Zoroastrian) corruptions of the authentic faith of Israel. While Pharisees would be considered the earliest rabbis, the Sadducees operated as priests and were more of a political force back then because they represented the priestly aristocracy and the power structure of Israel. For them, the duties of religion centered primarily around the Temple. The Pharisees, on the other hand, were a group of laymen more representative of the common people. It would be somewhat of a stretch, then, to say that we Democrats are more like them and that the Republicans are more like Sadducees. Members of both parties are always far too quick to claim to speak for “the American people” as if they represented everybody. Nobody is that prescient or enlightened.

4. What’s wrong with having “traders in the house of the Lord”? [p.196]

It depends upon what you’re trading and for what. What became “wrong” with such practice were the ways in which the “moneychangers” outside the Temple would cheat people coming to exchange their money or livestock just to be able to make a sacrifice for penance in the Temple. It could be compared to the questionable practice of the sale of “indulgences” instituted later by the Roman Catholic Church. These were monetary payments as a way, lay people were told, to reduce the amount of punishment they would otherwise have to undergo for their sins. People were taught by priests that by making those payments it would reduce their temporal punishment after death. It came to be referred to as the state or process of purification called Purgatory. This is exactly what Martin Luther objected to in his “95 Theses” because he felt that it was wrong to promise that souls would be relieved from purgatory based on a simple monetary contribution. He also felt that the pope didn’t have the right to grant a pardon from God. One shouldn’t ever have to “trade” something for that. Grace, while unmerited perhaps, is always a free gift.

5. “Women are more naturally good than men are.” Is our author showing her bias? Comments. [p.202]

No, I think it’s just her sense of humor and made more tongue-in-cheek than in a matter-of-fact way. The context of this statement, as you recall, is her explaining what’s taught in most Orthodox Jewish Day Schools in reference to the place of men and women in that culture – i.e., that men are given a greater responsibility and, naturally therefore, are at a greater risk of doing wrong.

6. I do not understand “tithing mint, dill and cumin” or even figs. What does this part of the paragraph mean? [p.203]

It would be like our paying an additional ten percent (a tithe) to the Church with every purchase we made at the grocery store – a ridiculous thought on its surface, which is why Levine points out that “the Pharisee’s prayer is a caricature, and might have brought a smile even on the faces of real Pharisee bystanders.”

7. How do you understand the Tax Collector receiving his justification “on account of the Pharisee”? [p.209]

As with many languages, prepositions can be “pesky” (as Levine notes). If the Greek para can mean not only “rather than,” but anything from “because of,” “alongside,” to (as you suggest) “on account of,” then you’ve any or each of those meanings from which to choose. If you do choose the latter, and understand the Pharisee as the caricature that he’s made out to be in this parable, then ranking sins and anyone’s relative worthiness to receive mercy is shown to be as ridiculous – unjust even – as it sounds. On the other hand, if (as Levine says) “the sin of one person can negatively impact everyone else” but “the good deeds of one person can have a positive impact on the lives of others,” the tax collector may have been so moved by the Pharisee’s example that he, himself now, has become a changed man. In that sense (again, as Levine points out) “the tax collector has tapped into the merit of the Pharisee” and been saved “on account of” his extraordinary example. In the end, I tend to agree with Richard Q. Ford’s response that “Far from being example stories, …Jesus’ parables are highly complex, puzzling descriptions of the way things are. … By creating provocative descriptions, Jesus lures his listeners into using their empathy to raise a multitude of questions in their efforts to comprehend.” [p.19, op.cit.]

8. Will the Tax Collector keep his job? [p.210]

Who knows? If his prayer is sincere (and not just temporarily approaching God in a moment of fear as we might call a fireman to save us from burning), he might find a different job. But he might apply his collections with more compassion and fairness. He’d still be viewed by many others of his community, however, as a Roman quisling. Is that a “real” sin or just a poor man trying to make his way through the harsh realities of a cruel and hierarchical system? There are myriad ways in which you and I all rationalize why we do not do everything that we should do – as in “do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can.” [By the way, this is not a quote of John Wesley’s, as some have claimed, but just sounds like something he would have said so often has been attributed to him.]

9. Political: Compare the Tax Collector with modern INS agents. [p.210]

As Levine rightly points out, “Once we judge one better than the other, we are trapped by the parable.” The same might be true if we try to compare these two – or any other problematic profession for that matter (e.g., petrochemical engineer, defense attorney, member of the Armed Services, et al.). In the harsh light of President Trump’s recent executive orders, we also need to be reminded that the responsibility of an agent of the Immigration and Naturalization Service is simply to determine whether or not to admit people and/or cargo into the United States – according to the law that he or she as an agent has sworn to uphold. If an INS agent believes the law to be unjust, however, what should s/he do? Resign? Choose to “look the other way?” Become like Harriet Tubman and covertly support a modern-day “Underground Railroad?” Who knows? We always have a choice. Always.

Week 5 Questions

The Mustard Seed

1 – How has the contrast of small to large been manifested in your life? 167 (Why has a mountain never moved from here to there?)

2 – why do you think so much ink is used on the purity laws of the Jews? 168

3 – What is the challenge in this parable? 171

4 – Assuming that Matthew and Luke used Mark as a source, why did the vegetable grow into a tree? 173

5 – When have you noticed the control/constraint applied to Jesus’ parables by the evangelists? 174

6 – How do you see the difference between the field and the garden? 176

7 – Our author describes how every story bit is made to establish a connection to some earlier story, perhaps a piece of the standard set of stories. How does this compare with how we use stories today? 179

8 – How does this parable, as a message of ecological adaptation and survival, apply to our world today? 181

9 – Which of the last three lessons do you most appreciate? Why? 182

My take on interpreting The Mustard Seed

I borrowed a page from Dorothy's book: First I read the three versions of the parable, did a little research, pondered, and came up with my own interpretation. (All of that before reading any of the chapter text or anyone else's postings.) Then I read Dorothy's and Jack's interpretations. At that point I thought mine was rather simplistic, indeed superficial compared (or comparabled?) to theirs... and still valid, still my view. This is it:

Apparently the parable mustard was “black mustard” that usually grew in fields. Luke had Jesus saying it was grown in a garden, perhaps for relevance to his audience who might not have been growing things in fields as may have pertained to Matthew's and Mark's audiences. In ancient Palestine or Galilee, black mustard when mixed with field crops may have been a nuisance plant; it was an annual that grew to perhaps a few feet in height. Mustard in those times was used for medicinal and perhaps other purposes.

“The mustard seed is the smallest of all the seeds on earth.” When Jesus said this, it must have been a widely understood factoid of that time. But when he illustrated the kingdom of God by comparing it to the tiny mustard seed, it’s a different story: It’s sowed or planted by a man who perhaps represents God. Upon sprouting and growing, this particular seed creates a dramatically different result. It becomes a huge tree, with branches large enough to accommodate birds, large enough to cast a shadow for comforting shade in a warm dry climate. A place for God’s creatures to live together in harmony, with natural cover to shelter them from enemies and the elements.

I think Jesus wanted his audience to be surprised with how different this one mustard seed is from the usual ones, not at all like what they would expect. If they were farmers, they knew about mustard and its seeds. Jesus started with the ordinary, then drew an entirely new picture – extraordinary – to make a point that the kingdom of God, growing here and now on earth, is an extraordinarily different way for people to live their lives.

Update 3/5/17: Upon finishing the last two pages of Chapter 5, I see that some of the author’s conclusions are along the lines of some of mine. Not certain what to make of that, but there you have it. I appreciate what she says on pg 182, second paragraph, about potential needing to be actualized. It’s long been my opinion that, while an objective overview of a given situation is essential, it’s necessary to give attention to details, to individual aspects that may be addressed or may progress independently to a natural and (one hopes) effective outcome.

Responses to Week 5 Questions

Week 5 Questions

The Mustard Seed

1. How has the contrast of small to large been manifested in your life? (Why has a mountain never moved from here to there?) [p. 167]

Well, I’ve watched our children and our grandchildren grow from “small to large.” I’ve found myself become larger than my father, then my children become larger than me. With the life comes the growing. As far as mountains moving, much of what I first learned about God has moved into the mist of my past and the anthropomorphic God replaced by a far, far deeper and larger Mystery. That’s one big mountain moved. But, again, you can’t take most of the Bible literally anyway – certainly not the parables. Right.

2. Why do you think so much ink is used on the purity laws of the Jews? [p. 168]

As Levine continues to point out (and rightly so, I think), much of the New Testament was a polemic against traditional Judaism for its perceived failure to recognize or accept Jesus as the long-waited-for Messiah. So, beginning with Paul and increasingly with positions taken by the early evangelists, then “People of the Way,” then “Christians,” then the institutional Church, the inheritors of this movement along with the authors and redactors of New Testament theology sought to justify the movement by pointing out how and why Christianity was so much better than Judaism. Overemphasis on “purity laws,” then, was just one more way that they did it; denigrating “the Law” over “the Gospel” became yet another. In the end, sadly, even the man from Nazareth became elevated to “the second person of the Trinity.”

3. What is the challenge in this parable? [p. 171]

The challenge to the reader (as well as to those who heard it originally) is just how we’re to understand that the Kingdom of God/Heaven actually can be compared to something as common as seed-planting and as ordinary (let alone extraordinary) as the growth that follows. We might find that disconcerting, but if we can only accept it as easily as birds do the branches and foliage of a tree, we too might find both sustenance and shelter in its ever-present yet still burgeoning presence.

4. Assuming that Matthew and Luke used Mark as a source, why did the vegetable grow into a tree? [p. 173]

The simple answer is that, as with all stories that are told and retold, many of the parables became rhetorically supercharged – i.e., with each retelling all too often the exaggerations increased, garden to field, humble bush to huge tree.

5. When have you noticed the control/constraint applied to Jesus’ parables by the evangelists? [p. 174]

Every single explanation of a parable (especially in the Bible!) is an editorial. But even if they don’t offer an explanation, as Levine points out, this is what happens when the evangelists cluster the actions, teachings and parables of Jesus around their own themes (not necessarily those of Jesus) – whether it be discipleship, kingdom-living, soteriology or expounding on teachings within the Torah. Again, Levine says it very well: “What makes the parables mysterious, or difficult, is that they challenge us to look into the hidden aspects of our own values, our own lives. They bring to the surface unasked questions, and they reveal the answers we have always known, but refuse to acknowledge” [p. 3].

6. How do you see the difference between the field and the garden? [p. 176]

It seems to me that a field would be much larger than a garden, and yet both would need tending. So, like #4, above, I don’t think the difference in size or location is homiletically significant. The difference happens simply in the retelling and becomes wherever that story teller wants to locate it. In that, I agree with Levine’s conclusion and “am not inclined to put too much weight on the import of the location for the parable. The seed goes where seed goes – into the ground” [p. 177].

7. Our author describes how every story bit is made to establish a connection to some earlier story, perhaps a piece of the standard set of stories. How does this compare with how we use stories today? [p. 179]

I think this is how we got the literary concept of “genre” (from the word “gender” in French). Many stories can be characterized as having a particular form, content, style or technique that then connects them with other stories that are very similar in one or more of those ways. Often, they get put in collections that exemplify that genre and so are read and interpreted in much the same way. The problems arise when some literary or theological critic then lumps them into a category in which they shouldn’t belong (i.e., that wasn’t the reason that they were told). As Levine is constantly pointing out to us, the classic example is assuming that every parable is really an allegory so we’ve got to then assign some deeply spiritual meaning or ecclesiological symbol to every concrete or material form within the parable. By constantly doing this (as she points out in her introduction to this book), we then “domesticate Jesus’ stories” and don’t leave them open enough to invite our deeper engagement with them. Sadly, then, it “destroys their aesthetic as well as ethical potential” [p. 1]. So, I just love it when Levine goes on to say how this “surplus of meaning is how poetry and storytelling work, and it is all to the good” [p. 2]. Yes, it is.

8. How does this parable, as a message of ecological adaptation and survival, apply to our world today? [p. 181]

As with every single thing that lives and grows here on earth, it can be destroyed. Wars and rumors of wars, cultural constraints, and the literal desecration of the very environment once made for life, all choke off any possibilities for good fruits. Growth itself can also become stunted and misshapen for lack of careful tending. Worse, any seed might never be planted and so remain a dry and empty pod, filled with only potential yet not even good enough for consumption.

9. Which of the last three lessons do you most appreciate? Why? [p. 182]

I prefer the third, simply because you and I would be involved in both the planting and the tending. Yes, some things need to be “left alone” and at times we should simply “get out of the way,” but precisely because “both images are of domestic concern” (the third lesson), human beings are involved. We’ve been given a responsibility. Either we become part of this planting, growing, tending – and, yes, harvesting – or the “Kingdom of God/Heaven” becomes only something that we long for or admire from afar, but never aspire to or strive toward (Because, after all, we’re not like Jesus!). So, we wait for God to intervene and save us from ourselves. And yet, truly, “The kingdom is present when humanity and nature work together, and we do what we were put here to do – to go out on a limb to provide for others, and ourselves as well.”

Week 4 Questions

Pearl of Great Price

1 – Could any of the interpretations up to footnote 8 be what Jesus had in mind when he told the story? Why? 140

2 – What positive or negative connotations do you associate with merchant? 142

3 – How do you value pearls compared to other “decorations”? 146

4 – Would you choose knowledge, sacrifice, or economics to understand this story? Why? 154

5 – Describe ho you think the merchant changed after (as?) he bought the pearl. 160

6 - “Are [you] willing to step aside from all [you] have to obtain what [you] want?” How have you demonstrated this? 161

7 – Is the Kingdom of God the same for everyone? 164

8 – What does the merchant do next?

My take on Amy-Jill's analysis of The Pearl of Great Price

1 – Could any of the interpretations up to footnote 8 be what Jesus had in mind when he told the story? 140 No. Why?

(1) Parable = Christian allegory of discipleship, focusing on person who chooses to seek the kingdom. Merchant is metaphorical model for Jesus’s disciple, and pearl is metaphor for gospel (“the good news of the kingdom”). Merchant sacrifices everything he has to obtain the kingdom.

Christian doctrines / theology hadn’t been invented / developed when Jesus was telling this short story. This interpretation over-complicates the story. It’s about the kingdom of heaven, finding it (perhaps the surprise of recognizing it when it’s in your face), and the value (or cost) of it.

(2) Parable = Christian allegory of discipleship, focusing on person who chooses to seek the kingdom. Merchant is metaphorical model for Jesus’s disciple, and pearl is metaphor for gospel (“the good news of the kingdom”). Merchant sacrifices everything he has to obtain the kingdom.

Christian doctrines / theology hadn’t been invented / developed when Jesus was telling this short story. This interpretation over-complicates the story. It’s about the kingdom of heaven, finding it (perhaps the surprise of recognizing it when it’s in your face), and the value (or cost) of it.

(3) Parable = allegory of Christ being the pearl, and us being the merchant who seeks security, fame, eternity; when we find Jesus, it costs us everything else we have including security, fame, security.

Jesus didn’t perceive himself as the Christ, nor the “one pearl of extremely great value” that would be worth a person giving up “everything” to possess. I think he applied that simile to the kingdom of heaven, as elsewhere he told the rich man who asked him how to have eternal life.

(4) Parable focuses on sin and redemption, because the earl is formed through great suffering and pain. (It’s not entirely clear to me how this interpretation works.) Note 7: “Margarites [“pearl”] and thesauros [“treasure”] refer to Jesus’s disciples (Matt 13:44–46… In the eyes of the God of grace, these sinful, imperfect disciples appear as treasure; nay, as pearls!” (“Parables of Atonement and Assurance”).

Jesus didn’t focus on sin and redemption.

(5) Metaphor of pearl being the Church; God is transforming us at great price from ‘strangers on earth’ into the image of Christ, with great pain, so as to produce the Church.

The Church didn’t exist in Jesus’s time. I don’t think Jesus imagined that God considered humans to be anything other than the rightful inhabitants of Earth. And I don’t think Jesus anticipated his actions and followers becoming so widespread (via Peter & others in Jerusalem and beyond, Paul & his followers throughout the Diaspora, and both of them in Rome) – nor of the “movement” becoming a “church”.

2 – What positive or negative connotations do you associate with merchant? 142

Negative: According to paragraph 2, he probably earned his livelihood from finding and selling luxury items (perhaps wholesale, via retailers) to people who didn’t need them and couldn’t afford them. (Gotta wonder what advertising media was involved…)

Positive, at least to my thinking: Apparently he wasn’t above succumbing, any more than his retail customers, to a hunger for something above and beyond the ordinary, for whatever reason(s). So his all-consuming purchase of the Pearl of Great Price brought him down to the reality experienced by his retail customers: no more merchant career (not having cash or goods to pay or trade for more merchandise to sell), thus no income to pay for the basic necessities of life let alone luxury items.

3 – How do you value pearls compared to other “decorations”? 146

Lovely to look at, but the price of good quality real pearls is far out of my range. Besides, I don’t “dress up” enough or often enough to wear even the nice cultured pearls I have! I value some of the other “decorations” I own because they’re thoughtfully-chosen gifts from family members or friends (colors & styles they know I like), some because I chose them as handmade works of art, some because special people in my life have created them for me. Their value to me is not in the dollars spent for them, or that I could sell them for, but in the love and appreciation of people who gave them to me or the artists who created them.

4 – Would you choose knowledge, sacrifice, or economics to understand this story? Why? 154

Upon rereading: Knowledge – no. Sacrifice – at a minor level, but it doesn’t express spiritual / religious sacrifice, and I don’t think it was Jesus’s main point. Economics – Levine points to several factors that reveal economic issues which she appears to find important, but she later sets aside economics as the way to understand the story. Anyway, I’ve never thought so. Therefore, I wouldn’t choose any of those.

I think I understand this story (and The Treasure Hid in the Field) being primarily about a person whose life is turned upside down, inside out, with a completely-unexpected CHANGE. From that point forward, it’s an entirely DIFFERENT life inside one’s own head, resulting in being a different person. And wasn’t that what Jesus was talking and teaching about back then? Still living in the “same” world / family / perhaps place, occupation, etc., yet now recognizing a new and different relationship with God and what the community believed was God’s creation. Especially manifested in the ways one related to/with one’s “neighbors” and environment, through a new perspective of meanings of scripture and teachings. So today we may choose the aspect of CHANGE to understand how the merchant’s story pertains to our lives.

5 – Describe how you think the merchant changed after (as?) he bought the pearl. 160

Considering of how he might have felt – emotions – and then thought about what had happened and the choice he had made:

“As” he bought the pearl, in the moment of finding himself to be its owner – Perhaps the most elated he had ever felt in his life!

“After” – are you asking about the rest of his life? Well, at least for starters… Doubt, regrets, “OMG, what have I done?!?” alternating with return to the initial joy.

And so, he would be transitioning from the merchant he had been to this new person, the owner of the unique treasure. I imagine him exploring and learning and being the new “who” that he made himself into.

6 - “Are [you] willing to step aside from all [you] have to obtain what [you] want?” How have you demonstrated this? 161

I don’t think I’ve actually done that, entirely, 100%. Due to childhood and youth circumstances and challenges, I was not exactly a self-confident young-to-middle adult. I usually felt rather insecure so was not inclined to step out in risk to seek what I wanted. And much of the time, I was uncertain about what I wanted.

Later on, I came to understand the value of choosing goals (discernment) and working persistently to achieve them (creating a path and following it), and became much more focused and intentional at being “my own person”. While I may not have stepped aside from all I had in order to obtain what I wanted, most definitely I have – multiple times – done the life business of setting a goal, stepping away from significant “personal possessions”, and progressing with persistence to the achievement of the goal.

Indeed, a number of the goals I’ve reached have had value not only in the moment of accomplishment but also ongoing and future value, for myself and for other stakeholders. Those goals achieved weren’t sudden surprises, of course. Still, with those experiences I can put myself in the merchant’s sandals to have a sense of how he felt after he bought the pearl and how it changed him.

7 – Is the Kingdom of God the same for everyone? 164

Of course not. And that pertains to the Kingdom of God that Jesus proclaimed is here now, as well as to the “treasure in heaven” that many people believe awaits them in a celestial afterlife. As an adult, I haven’t dwelt in that latter expectation but instead have sought to “do what’s right” in the here and now. If it does build up treasure in heaven, fine. if all it does is to make anything better in any way for any creature or any other thing on or around Earth, so much the better. (Thank you, John Wesley, for your guidance.)

8 – What does the merchant do next?

As stated for #5 – Live life as the owner of the unique treasure, exploring and learning the new “who” that he has made himself into.

Responses to the Questions about The Pearl of Great Price

Week 4 Questions

Chapter 4 – Pearl of Great Price

1. Could any of the interpretations up to footnote 8 be what Jesus had in mind when he told the story? Why? [p. 140]

Maybe, but I don’t think that Jesus would ever be talking about himself (i.e., that he is the Christ, “the Way, the Truth and the Life,” …that pearl for whom we all must be seeking). At most he’s trying to point us in the right direction – often to what’s right in front of our noses. I don’t think that he’d be talking about “the Church” either – at least as we’ve come to know it (e.g., “purchased with the blood of Christ” and a top-heavy institution filled with hierarchies, doctrine and dogma). But if there is a god and that god is “transforming us into the image of His Son” – into someone like Jesus – that might be, indeed, a “pearl” worth, not just having, but being.

2. What positive or negative connotations do you associate with the merchant? [p. 142}

He’s searching for something better in his life – even if he doesn’t know, yet, just what it is. That’s always a good thing. He’s persistent. That’s also positive. If he’s not quite willing to “give up” everything that he has for that better thing, at least he’s willing to sell all that he has to have it. How many of us would do that? The negative side of the merchant, on the other hand, is this assumption that everything can be bought or sold, that everything has a price. As Levine points out, “this makes the kingdom a commodity” [p. 140]. And yet, even as I hear that, if there is no cost then what, if anything, is the meaning and depth of the value received? And, never mind the “pearl” (which has for so long been the central focus in the interpretations of this parable), how can “the kingdom of heaven” be anything like this money-grubbing merchant, which is actually how the parable is introduced?

3. How do you value pearls compared to other “decorations”? [p. 146]

“Diamonds” are still “a girl’s best friend.” Oddly enough, however, while in my wife’s North Carolina tradition a string of pearls would be a wonderful addition to any wedding, one of our daughters-in-law (this one from Chile) says that her culture associates them with death and funerals. She told us that people from Chile refer to them as “tears of sadness.” Not surprisingly, at her and our son’s wedding we did not give her a string of pearls to wear!

4. Would you choose knowledge, sacrifice, or economics to understand this story? Why? [p. 154]

I think that all three are at play, but not in quite the “either/or” way that Levine presents them. The merchant longs for something more. He knows this. That kind of knowledge is a good thing. Without it you would never be moved to change. At first, he acts like any merchant would in this pursuit as he responds to his deepest longing. All that he needs to do, he thinks, is buy what he’s looking for. And yet when he does find his “pearl” he makes the ultimate sacrifice – one most any merchant would find unimaginable: he sells everything that he has in order to get that pearl. As Levine points out: “the merchant sold more than just his merchandise….” He sold all he possessed: “his home, food, clothing, [and] provisions for his family if he had one.” But what he has won’t “nourish, shelter, or clothe” him [p. 150]. Even “though initially a man of some substance [he is] impoverishing himself to acquire something supremely valuable which he could admire and display but could not live off [of] unless he sold it again” [pp. 150-151]. It doesn’t make sense. And yet the price that he paid “is not a sacrifice, but an exchange of something lesser for something greater” [p. 153]. In that, the merchant seems to know what he was doing, even though in the normal economy it seems just plain stupid.

5. Describe how you think the merchant changed after (as?) he bought the pearl. [p. 160]

I agree with Levine who notes that, “By finding that pearl of ultimate worth, the merchant stops being a merchant” [p. 152]. He stops looking for anything more. Any other merchant would be looking for the next transaction, the next deal. As Levine puts it, “He changes his focus from the many to the one, and he stops looking” [p. 159]. What’s more, “the ‘magnitude of the life change,’” as Levine points out, “is paramount; he is no longer what he was.” I would add, neither is he who he was. Everything that he used to want or desire has changed because he’s found the “pearl” that he really wanted all along but never knew it until he discovered it.

6. “Are [you] willing to step aside from all [you] have to obtain what [you] want?” How have you demonstrated this? [p. 161]

I don’t think that I’ve ever fully demonstrated this. I gave up a promising and lucrative career to enter the ordained ministry. I gave up our home and moved away from the settled community in which we lived. Financially, I went backward. Emotionally and spiritually, however, I went forward. But I took my family with me; in that sense, I did not turn away from all that I had – nor would I. My family is my greatest treasure, “the pearl of great price” from which only death will separate me.

7. Is the Kingdom of God the same for everyone? [p. 164]

If it’s real then – like “liberty and justice for all” – it must be meant for everyone; but it certainly isn’t understood in the same way by everyone. For some it’s a mythical place only to be fully understood after death (as in the traditional concept of “heaven”). For others, it’s a metaphor for a life fully lived in the present. Levine is on to something, though, when she says, “There is a transcendent quality, a mystery, to this pearl. And so the parable provokes” [p. 161] – as all good parables do. But Levine compounds the provocation by reminding us that “The kingdom is not the pearl, and it is not the merchant…. the kingdom is like a merchant who seeks pearls and who, upon finding what he was not expecting – the greatest of the great – makes every effort to attain it” [p. 160]. That seems to say, at least to me, that the Kingdom is an action and not a commodity to be bought or sold nor a person to emulate or follow. Just what that action is may only be known for each of us in and through our own experiences of life. But we will know its value the moment we recognize how much it means to us.

8. What does the merchant do next?

He “lives happily ever after” with his family. Well, if I were him, family would have to be part of such happiness. Whatever he does, he is now fulfilled because he’s finally found the one thing that he’s always wanted and needed – even though he hadn’t known before what it was. With that discovery, to borrow Levine’s words, “surely we [all] must find a new way to live” [p. 164].

Week 3 Questions

Parable of the leaven

1 – What do you notice about Matthew and Luke’s versions compared to Thomas’s of this parable? 117

2 - “Any parable with a reference to leaven, ...” This paragraph is anachronistic, so should later references be set aside while we consider this parable? Obviously the parable comes before “this appetizing accompaniment.” 120

3 – Describe your sourdough experience. 122

4 – What is the problem with “the yeast of the Pharisees and Sadducees!”? 123

5 – Why do you think the pure/impure issue is so often associated with this parable? 126

6 – How have “the boundaries between the sacred and the profane” changed over time? 128

7 – Why do we hide things? 132

8 – What do you find most interesting about “three measures of flour”? 135

9 - “the kingdom of heaven [is] present when women [are] in the kitchen, barefoot, pregnant, and baking.” Comments? 137

10 – Does our author provide too much answer for the question “What does this parable mean?” 137

3 - Describe your sourdough experience. 122

My maternal grandfather, Clyde Frederick Gimple, must have idealized himself as a Forty-Niner. Apparently at some point before I was born (1941), he had made his way north of Hayfork, in Trinity County, where he staked a gold-mining claim that had a bubbly little creek running through it. He named the claim Bear Wallah because he once saw a bear a-wallahin’ in the creek. When he’d go there to pan for gold, he cooked his food 49er-style over an open campfire – boiled coffee, cast iron skillet for breakfast and dutch oven for a pot o’ beans or stew, homemade sourdough starter for hotcakes and bread, etc. Back in civilization (Hayfork, Weaverville, Napa, Chabot Acres where American Canyon is now, and wherever in between), he faithfully maintained his starter to bake bread, fry hotcakes, add dumplings to stews or cobblers, in or on whatever stove was available. Best hotcakes ever! Eventually he taught us how to make starter and cook with it. My Dad was an avid fly-fisherman (tied his own flies, made his own rods) who would take two weeks off each summer to fish the back-country rivers and streams for rainbows, cut-throats and German browns. We (mostly) loved those camping vacations and the times in Trinity County with Grandma and Grandpa. My sister Margaret and I took charge of laundering Grandpa’s denim overalls after each gold-panning excursion, because he’d capture more gold dust in the rolled-up cuffs of those pants than in the pan. We’d be very careful emptying the big galvanized washtub so we could collect the gold dust. I still have a little jar of it. And yes, I still know how to make and cook with starter.

Responses to the Parable of the Leaven

Week 3 Questions

Chapter 3 -- Parable of the leaven

1.What do you notice about Matthew and Luke’s versions compared to Thomas’s of this parable? [pp. 117f. and 131]

Matthew and Luke are very similar; Matthew uses the phrase “kingdom of heaven” while Luke uses “kingdom of God,” but in their etymological sense they’re speaking about the same thing (Most Jews would avoid using the name “God”; “heaven” was the acceptable substitute.) so it doesn’t appear that either have edited the parable. Thomas changes that same phrase slightly, yet again, and renders it “Kingdom of the Father.” And, as Levine points out, while Matthew and Luke make the leaven their focus Thomas, on the other hand, “compares the kingdom not directly to the yeast, but to the woman who took the yeast” (p. 131) -- additionally, I notice that Thomas has called her not just any woman but “a certain woman.” Even so, the focus doesn’t seem to be on her as much as what she does with that sourdough starter. Thomas also never mentions the oddly exorbitant amount of flour (”three measures”) but only says that the woman “concealed it in some dough, and made it into large loaves.” He also has Jesus adding the admonition, “Let him who has ears hear.” That last comment, though, sounds like an edit to me; most skilled rabbis wouldn’t deliver such a warning but would let the parable speak for itself (i.e., deliver its “hidden” counsel within the parable).

2.“Any parable with a reference to leaven, ...” This paragraph is anachronistic, so should later references be set aside while we consider this parable? Obviously the parable comes before “this appetizing accompaniment.” [p. 120]

I’m not sure Levine is insinuating here that the parable is somehow foreshadowing what’s to be said later in John’s gospel about Jesus. Any Jew would be reminded by this parable that bread is both “appetizing” and “nourishing.” As a Jew herself, though, it seems to me that Levine wouldn’t be equating the metaphor with Jesus. It does sound like her, though, that she would remind us Christians that there very well may be “more going on in the parable than a lesson on ‘the growth of the kingdom.’”

3.Describe your sourdough experience. [p. 122]

Freshly baked, still warm, and with a soft center, it’s delicious with melted butter. I’ve since come to learn, though, that sourdough is unique in that it’s bread made from the wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria naturally occurring in the environment. Traditionally it’s been made from just three ingredients: sourdough starter (created from flour and water which has been left out to ferment), salt, and more flour. It has no commercial baker’s yeast, no milk, no oils and no sweeteners. So, it’s about as “natural” as you can get when it comes to bread. I also have learned that the tangy taste of sourdough actually comes from the same bacteria that gives yogurt and sour cream their tartness.

4.What is the problem with “the yeast of the Pharisees and Sadducees!”? [p. 123]

I suppose the question would be, “What’s the ‘yeastiness’ of those two groups got to do with any later comparison to the Kingdom of God?” On the other hand, if the fermentation process is simply left to continue (i.e., without then being added to the salt and further flour) you may have a “pleasant sour smell” for a little while, but later it surely will become a “product of corruption”...“one of putrefaction” [p. 122]. As Levine notes on the following page, such “leaven ‘of the Pharisees’ is to be avoided, but not the leaven that Jesus offers.” [p. 124]

5.Why do you think the pure/impure issue is so often associated with this parable? [p. 126]

As Tevye noted in Fiddler on the Roof, it’s simply, yet problematically, been a matter of “Tradition.” Even if, in the Ancient Near East, both women and yeast were not necessarily viewed as ritually “unclean,” as Levine rightly points out, “it is true that in religion, especially [within] purity codes, women were at a disadvantage.” So I’m reminded that in many cultures ruled by men, “women’s work” has become thought of as “dirty work” and a man wouldn’t “soil his hands” to do any of it. That says more about the men than it does the women.

6.How have “the boundaries between the sacred and the profane” changed over time? [p. 128]

Much of what has been considered “profane” for many centuries has largely been established by religion -- especially in the areas of gender, sexuality, and food. What seems true to me is that the opposite may be more accurate: There is far more about life and the environment in which we all live that is more sacred than it is profane -- and yet sadly, still, we do not see it.

7.Why do we hide things? [p. 132]

Because we don’t want others to see them.

8.What do you find most interesting about “three measures of flour”? [p. 135]

It’s a whole lot of flour -- in fact a little over a bushel or about 144 cups of flour. That would be enough to give you about 52 loaves of bread each weighing about a pound and a half! To put it another way, you could make well over 400 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with that much bread! So what this woman is proposing to make would feed a whole lot of people.

9.“the kingdom of heaven [is] present when women [are] in the kitchen, barefoot, pregnant, and baking.” Comments? [p. 137]

It is. And it’s just as present when they’re not.

10.Does our author provide too much answer for the question “What does this parable mean?” [p. 137]

No, because the interpretations ought to just keep coming; that’s one genius of the genre. So I am deeply moved by Levine’s additional three possibilities:

1) “Perhaps the parable tells us that, like dough that has been carefully prepared with sourdough starter or a child growing in the womb, the kingdom will come if we nurture it.”

2)...or, “given the enormous yield...perhaps the parable speaks to the importance of extravagance and generosity.”

3)“Or finally, perhaps the parable tells us that despite all our images...the kingdom is present at the communal oven of a Galilean village when everyone has enough to eat. .... It is something that works its way through our lives, and we realize its import only when we do not have it.”

Week 2 Questions

The Good Samaritan

1 – How do you understand the difference between addressing Jesus as “teacher” vs “Lord”? 84

2 – What is wrong with “put(ting) the Lord your God to the test”? 84

3 - “The lawyer is literate.” How does Jesus know this? 87

4 – Is the “do” in Lk 10:28 a different word than the “do(ing)” Lk 10:25? 90

5 – What kind of status does “the priestly role” get you in today’s society? 98

6 – What’s the difference between a good person and good deeds? 105

7 – What value do you see in our author’s (long) description of Samaritans? 105+

8 – Compare mercy and compassion. 114

9 – What do you know / think about this parable that is now new? 115

Response to Week 2 Questions

Week 2 Questions

Chapter 2 -- The Good Samaritan

1.How do you understand the difference between addressing Jesus as “teacher” vs “Lord”? [p. 84]

The latter title was bestowed upon him by the early evangelists. It was meant as an honorific title in keeping with their tradition. The result, however, has come at the expense of the former. Due to this emphasis by the Church, Jesus’ humanity has been lost to us and he was practically “elevated” to an exclusively divine status (i.e. in the doctrine of the Trinity). Far from being helpful to us, then, in living out our own lives, it’s made Jesus more distant -- even separated him from his own reasons for demonsrating what it means to be a fully human being by being a good teacher and exemplar.

2.What is wrong with “put(ting) the Lord your God to the test”? [p. 84]

I’ve always considered that the line, “Lead us not into temptation” meant “Don’t put me in any situation that I can’t handle.” But it also assumes that “the Lord your God” is more like the human tyrants that we’ve all known than the Sacred and ineffable Mystery that God actually is. If we cross “Him,” we’ll be punished. Such a divinity is meant to “scare the Hell out of us,” rather than teach us how to love and be in relationship with our neighbor.

3.“The lawyer is literate.” How does Jesus know this? [p. 87]

In that era one of the few groups of people that actually knew how to read and write were those schooled in the Torah (or the Law): the lawyers.

4.Is the “do” in Lk 10:28 a different word than the “do(ing)” Lk 10:25? [p. 90]

It’s relatively easy to “do” good toward others who “do” good toward you (i.e., friends and neighbors with whom you are close), but to actually “do” good toward the neighbor whom you do not know or (as in this case) one whom you’ve been taught to despise, is much harder. But that’s exactly the kind of “doing” that Jesus is speaking about here. As Levine points out, this “imperative ‘do’ focuses not on a single action, but on an ongoing relationship.”

5.What kind of status does “the priestly role” get you in today’s society? [p. 98]

Well, it gets you into hospitals. But at least now it’s considered to be a vocation and not just an inherited position reserved for the elite. More importantly, however, it gets you into the lives of people who are asking for or seeking spiritual direction in their lives. The “priestly” role is, then, a role given to one who is able to be an intimate companion to those who desire to enter more deeply into this sacred journey because they, themselves, are living it.

6.What’s the difference between a good person and good deeds? [p. 105]

You will often know the one by the other. In that sense, orthopraxis is far, far more significant and important than orthodoxy. But while the saying is true that “You will know them by their fruits” (Matthew 7: 16a), sadly, there are those who will always try to achieve “goodness” solely by doing “good deeds.” It just doesn’t work that way.

7.What value do you see in our author’s (long) description of Samaritans? [pp. 105 ff.]

History is more than just a story. The background that Levine gives us here is invaluable. Assuming the role of “devil’s advocate,” I think that the longer the conversations the deeper will become the possibilities for dialogue. The more true dialogue in which we engage, the more we may begin to understand and appreciate our differing points of view. The more that we begin to fully understand and appreciate those points of view that differ from our own, then, the more tolerant and accepting of diversity we may become. Sadly, without true dialogue the results, all too often, have led to bigotry, dogmatism, narrowmindedness, sanctimoniousness, prejudice, hyperpartisanship, injustice, racism, sexism, chauvinism, dishonesty...and much, much worse.

8.Compare mercy and compassion. [p. 114]

I think that when Jesus spoke of mercy he was saying that you will truly receive mercy when mercy actually becomes a part of you. In that sense, compassion is “just” a feeling, a caring about others -- and yet such a deep and powerful awareness of the suffering of others that you then are moved to relieve them of it. Mercy may be understood, then, as actively sharing the same kind of compassion that has, first, been shown to you. In that sense, I think mercy is much more like grace in that it meets us where we are, but doesn’t leave us where it found us. We act upon it and so are transformed. Another way of putting it might be to say that mercy is the fruit of compassion. The one takes root and gives rise to the other.

9.What do you know think about this parable that is now new? [p. 115]

Most people haven’t known just how despised Samaritans were in the context of this parable. Hearing the story then, yet again, it’s caused me to ponder its message in a deeper way. It might be like my being cared for and shown such compassion by someone who is an avowed whites-only neo-Nazi. Even the thought of that being possible seems incomprehensible! And yet, as the parable challenges us in confrontation with our enemies (and Levine contextualizes), “Will we be able to bind up their wounds rather than blow up their cities? And can we imagine that they might do the same for us?” May it happen... some day.

Week 1 Questions

Introduction

1 – Explain “Surplus of Meaning”. 2

2 – Compare the parable on pg. 5 with our current political situation.

3 – What parable of Jesus do you find least understandable? Why? 12

4 – Do we do our children a disservice by using (explaining) Jesus’ parables as “children’s sermons”? How? 21

Chapter 1

5 – In your previous parable study how (much) have you been “set up” by the evangelist’s bookends? 37

6 – When have you failed to notice what is missing? 38

7 - “The seeker who leaves 99 sheep to find one will have, at the end of the day, only one.” Comments? 39

8 - “...the joyful finder served mutton.” Comments?

9 – What effort have you taken to find your lost (sheep)? 45

10 – What is your impression of the very close reading of the father and sons parable? 54

11 – What specific (new) details of this story do you find most interesting? 64

12 – Is Jesus’ message all along, “Instead, go have lunch.” or is this not only the wrong answer, but the wrong kind of answer? 75

Responses to the Introduction and Chapter 1

Week 1 Questions

Introduction

1.Explain “Surplus of Meaning.” [p. 2]

As Levine notes on the previous page, “Reducing parables to a single meaning destroys their aesthetic as well as ethical potential.” An English theologian, C.H. Dodd, has given us the classic definition of the parable: “At its simplest the parable is a metaphor or simile drawn from nature or common life, arresting the hearer by its vividness or strangeness, and leaving the mind in sufficient doubt about its precise application to tease it into active thought.” [The Parables of the Kingdom, p. 16] In other words, our first thought might not be the correct interpretation. Not only would the parables probably be heard and interpreted differently at the time that Jesus spoke them, if their message doesn’t disturb or indict those who hear them (then as well as now), then they’ve missed their deeper meaning. In that sense, they may be a bit similar to a Zen koan which presents a paradoxical (even nonsensical) question for which an answer is demanded -- and it’s the stress of meditating on the question that can lead to deeper and deeper illumination. The meaning of all parables can and should expand and, thus, hold a “surplus of meaning.”

2.Compare the parable on pg. 5 with our current political situation.

“Take refuge in my shade” could be Trump’s line -- i.e., “I’ll take care of you. Don’t worry. I know better than anybody what’s best.” But we forget, like any bramble, if we allow him to grow and take root in the midst of us, we’ll not only no longer be able to freely move about, we will begin to be torn apart by the bramble itself.

3.What parable of Jesus do you find least understandable? Why? [p. 12]

First, of all of the more traditional “biblical” parables that we know about (a total of 33 -- if you include the parables in the Gospel of Thomas), the Jesus Seminar ranks only 21 as “red” or “pink” or probably authentic. The other 12, then, have been ranked “gray” or “black” and so are considered by the scholars as inauthentic. I take some comfort, then, from the fact that the one I find least understandable is the one called “The assassin” (in the Gospel of Thomas) and it was voted “gray.” It’s this:

“The Father’s imperial rule is like a person who wanted to kill someone powerful. While still at home he drew his sword and thrust it into the wall to find out whether his hand would go in. Then he killed the powerful one.” [Thomas 98: 1-3]

How is this a parable about God? What difference does it make whether or not his hand goes into the wall along with his sword? What is the wall? Who would God want to kill and why? And, finally, who is the “powerful one” that he does kill? You tell me.

4.Do we do our children a disservice by using (explaining) Jesus’ parables as “children’s sermons”? How? [p. 21]